Disabled in Dhaka

Anyone, at any time in their life, can become disabled. Only a fraction of the disabled people were born with disabilities. Despite this fact, disabled people are among one of the most marginalised communities to exist. Popular discourse in Bangladesh (and other parts of the world) dictates that disability is a curse, often believed to be contagious. Other times, people believe it occurs because of misdeeds in past lives.

None of that is true.

A disability is any continuing condition that puts restrictions on an individual's day to day activities. This can include learning, intellectual and developmental disabilities, mental illnesses, sensory impairments, and temporal disabilities. However, disabilities are more than what someone is mentally, physically, or emotionally. It's a significant aspect of people's identities and it often determines not only how they are treated by the world, but also how they interact with them.

According to a 2016 report by the World Bank, 16 million people in Bangladesh are disabled, which is roughly 10 percent of the country's then population. Despite this number, they are not represented in most workplaces or educational institutes across the country. Speaking to a representative from a reputed private university in Dhaka, statistics revealed that only 0.5 percent of their 3,000 strong workforce and 0.15 percent of their 22,000 students consists of disabled people.

When asked if they have programs that specifically aim to recruit disabled people, either as students or employees, they respond, "No. We don't discriminate based on disabilities, there aren't any pay discrepancies, so if we get their application, we will consider them just as we would any other applicant. We don't see why we should go out of our way to recruit them when they can just as easily come to us."

When asked if the institution makes any special adjustments to accommodate disabled people within their community, they said, "No. They don't take up a lot of space, so I don't see why we should. If they made up more of our community in terms of numbers, we would, of course, consider investing in special facilities for them."

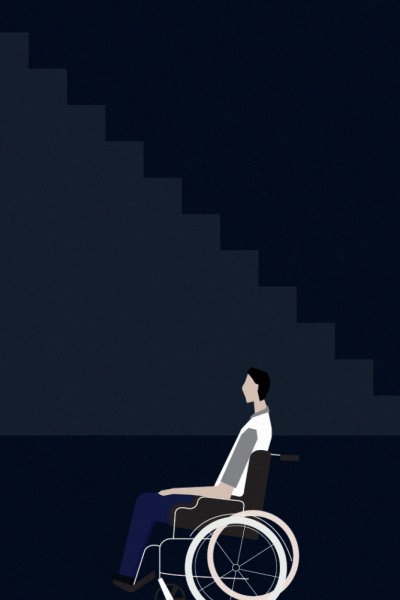

But this is precisely where the problem lies, isn't it? When there's no investment in special facilities for disabled people, it deters them from wanting to participate, or in some cases, makes it impossible, which in turn reduces the number of disabled people seen in public, prompting people to think they're an outlier and deem that there isn't much of a need to consider them or make special considerations, bringing us back to square one. This is the cycle of inaccessibility. With the social stigma that already exists surrounding people with disabilities, organisations should make it clear that they are disabled-friendly by investing in accessible facilities.

This problem isn't just prevalent in workplaces, though. It's embedded in every aspect of our society. Public transportation in Dhaka rarely has accessible facilities. Our washrooms aren't big enough for wheelchairs to comfortably roll around in. Even something as low-effort as a wheelchair ramp is unavailable in most buildings, and nor are there elevators big enough for wheelchairs to fit in.

There needs to be a collective effort from more people if we want to normalise disability and make Dhaka more accessible. Disability rights foundations have been at the forefront of this movement but it seldom garners support from people who have the power to make a change. Perhaps the biggest responsibilities fall on parents, educational institutes, and the media. Representation matters and these are the places where children learn from most. While progress has been painstakingly slow, Bangladeshi media is finding new ways to represent disabled people. However, that doesn't mean that we should overlook the fact that prejudice against disabled people rooted in our society has largely been because of a lack of representation in the media over the past few decades. Even today, agencies and institutions should be doing more than just the bare minimum.

Most often, students with disabilities note how difficult it is for them to go to school without being discriminated against by teachers and bullied by their peers. Sabahun Salam, a high-school senior who has significant experience working with children with disabilities notes how important it is for students with disabilities to be able to go to everyday schools. "They shouldn't go to special schools because that effectively disintegrates them from society. This is what normalises the use of words like 'autistic,' and 'pongu' as an insult. It makes people think that disability is something abnormal just because they aren't used to seeing disabled people every day, and in the end, what this does is make it impossible for both communities to know how to communicate with each other."

Despite being an aspiring basketball player who has often been the victim of temporal disabilities, Sabahun argues that she barely knows what it's like to be disabled. She's not wrong. She says that when children don't make friends at school, this isolation is carried out onto adult life, "You know, it's not that difficult. Schools need merely one small special education department that can effectively help disabled students get integrated into society, but a majority of schools aren't ready to do that. All these kids need is a community."

Speaking to a representative from International Hope School, Bangladesh, I learned that the school has made some improvements over the past couple of years to be more accessible for disabled students, installing ramps and elevators on all its campuses. However, the fact remains that the school does not cater to the visually and hearing impaired.

"Teachers need very high levels of training to cater to the needs of these children. I think that it's better for them to go to special needs schools where the teachers were trained to attend to their needs, like providing books in Braille. However, we have trained our teachers in the differentiation curriculum so that they can support visually impaired students. In the future, we hope to do more meaningful work like this," comments a school representative.

Even though the school makes special efforts to incorporate students that have physical and learning disabilities, not a lot of strides have been taken to effectively integrate students with other kinds of disabilities. "We do intend to make more improvements over the next few years so that we can accommodate as many students as we can. Education should be accessible for all," the school adds.

It's very hard to set out all the needs of disabled people because of what a wide definition that is. Each type of disability requires a different kind of accommodation. However, in order for us to cater to the needs of all disabled people, we have to first normalise disability, and the responsibility of that falls largely upon the media and educational institutes.

Moving forward, let's remember to be less ableist. Disintegrate words from our vocabulary that villainise disability. Value unlearning just as much as we do learning. Let's talk about disabilities. Make space for accessible parking. Ask if our spaces are accessible for people with disabilities; are our graphics readable? Do we make efforts to incorporate Braille into everyday life?

Let's stop looking at disability organisations as a way to boost resumes. We can only move forward as a society when we accept that disabled people are people, just like us.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments