How related is Parliament to the Public?

Parliament claims to be the most representative branch of a state and marks itself as a safety valve against democratic failure and authoritarian take over. As a watchdog of the executive's horizontal accountability, parliament has a vertical accountability of its own. This accountability is towards the people who elect and send the MPs to represent them. This is too important an aspect to be underestimated or ignored. A "Westminster parliament" is institutionally subdued by partisan whipping and cabinet control over its proceedings. While parliamentary committees were expected to fill in some of those gaps, Bangladesh's parochial party system hunts this prospect too. Given this seemingly unavoidable dichotomy, Parliament's increasing resort to its base – the People, must be considered seriously. If People have trust, expectation and communication links with their representative institution, it gets an alternative reservoir of strength against an otherwise invincible executive.

The usual public engagement strategies of world legislatures reveal a two-stage model of public relations. Firstly, they emphasise better informing the people about their work which help a trust building. In the next stage, parliaments would open up for public participation which would generate a continuous, distinct from a once-in-a-five-year, legitimacy for the institution.

Public relations tools like parliamentary publications, television and radio broadcast of the parliament at work, news and media coverage of parliamentary business, observation from public gallery, parliamentary education and outreach programs, official websites of parliament, its officers, committees and MPs should constitute the stepping-stones in the engagement process. Despite accessibility barriers, internet has played a remarkable role in opening up the parliaments. Internet has created an "e-constituency" where citizens and their representatives contact and interact directly and bypass the partisan channels.

At the next stage of public relations, parliamentary internships, outreach programs, weblogs and interactive social media outlets, public e-petition, participation in committee hearings, legislative consultation etc would poster interaction beyond mere dissemination. Advanced parliaments are increasingly using tools like e-petition and online publication of, and consultation on, draft laws. Parliamentary committees also hold online and physical consultations on current topics of their enquiries. Our experience in Bangladesh, however, shows that even an explosive level of online and social media revolution has failed to generate an extended culture of public awareness for parliament.

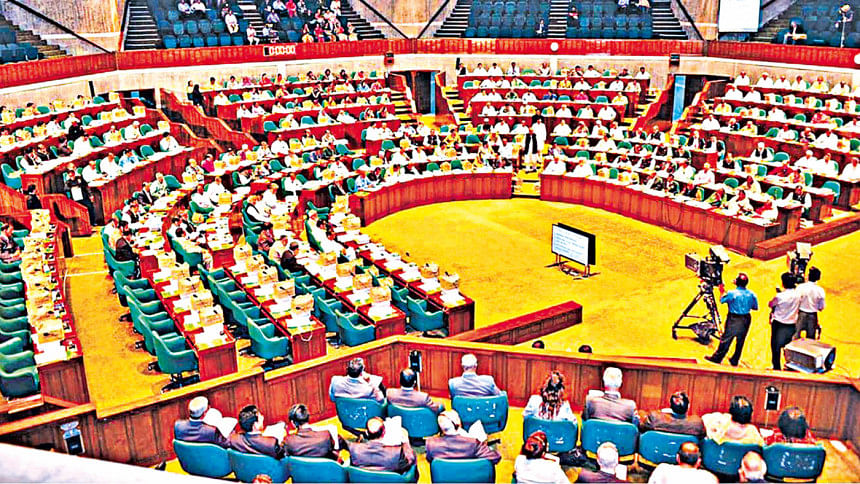

Bangladesh parliament is formally designated as an open institution. Though the Rules of Procedure (RoP) permits occasional sitting in camera, the sessions are mostly public. There is a scope of people physically observing the parliament in session. The actual access however is still a privilege rather than a right. Rule 201 of the RoP requires the withdrawal of media and non-members from the committee rooms. Committees are given the power to call witness testimony from the public, civil society or experts. Subject to some exceptions, committees in general have not shown any serious sign of awareness of the public relations tools they have in their disposition. Nor did the committee members and MPs show much inclination to value the alternative points of views and draw therefrom.

Parliamentary proceedings are recorded and printed verbatim. Absent the digitalisation of those, as is done by the Hansard Society in the UK, public access to the physical copies are extremely difficult. The parliament website (www.parliamentbd.gov) uploads the order paper for each day. Recordings of the proceedings however are missing. Since January 2011, parliamentary sessions are being broadcast in parliament TV (Sangsad Bangladesh Television – SBT). Those however are not live streamed in the parliament website. There is an official facebook page of parliament which live shares the sessions. Also, the leaders and MPs of the ruling party share those in their respective social media outlets. Opposition MPs however rarely show any interest in doing the same. During the observation process of my research, I have to rely excessively on those facebook pages which lack any stable URL. Hence there is no accessible authentic depository of the records. Comments and reactions of social media audiences to those live sessions are rather despairing. It appears that observation of parliamentary sessions in Bangladesh might involve a reverse risk of alienating the people from parliament. Unruly behaviour, unparliamentary words, irrelevant talks, almost zero oversight zeal and open submissiveness of the MPs to the government are most likely to end up in conveying a very negative image of parliament.

The media centre of parliament is mainly used for partisan press conferences and it is yet to make any significant contribution in public engagement and understanding of parliament at work. Newspaper coverage of parliamentary proceedings is also limited. Except on the day of budget speech and except when something very negative happens in the floor, parliamentary sessions rarely make headlines. In search of clues to the policy stance of government, print and electronic media would rather look towards public rallies and party programs. The law and social science schools and public policy study groups rarely show interest in parliament at work. Visit and lecture of the Speaker, Deputy Speaker, Whips, MPs and parliamentary officials to the universities are simply unknown.

Public engagement is increasingly perceived as the most significant trust building and legitimising tool for parliaments around the world. Two historic transitions of the post WW-II parliaments in Germany from autocracy to parliamentary democracy (1946 transition in the West and 1990 transition in the East) confirm that public awareness of parliaments increases with incremental familiarity, increased educational opportunities and easier access to information and it actually facilitates the gradual emergence of activist parliaments. There is however an agreement that a mere one-way information sharing with the public, which is mostly the case with the meagre public relations of Bangladesh parliament, may not be enough. While the parliament's accountability relation with the executive has been discussed almost continuously, we have surprisingly failed to talk its relation to the public. By and large, it has remained a closed institution unconcerned about engaging the people. In one sense, this perhaps reflects the sheer marginalisation of our parliament in public policy and democratic discourse.

The writer is PhD Candidate (Parliament Studies), King's College London.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments