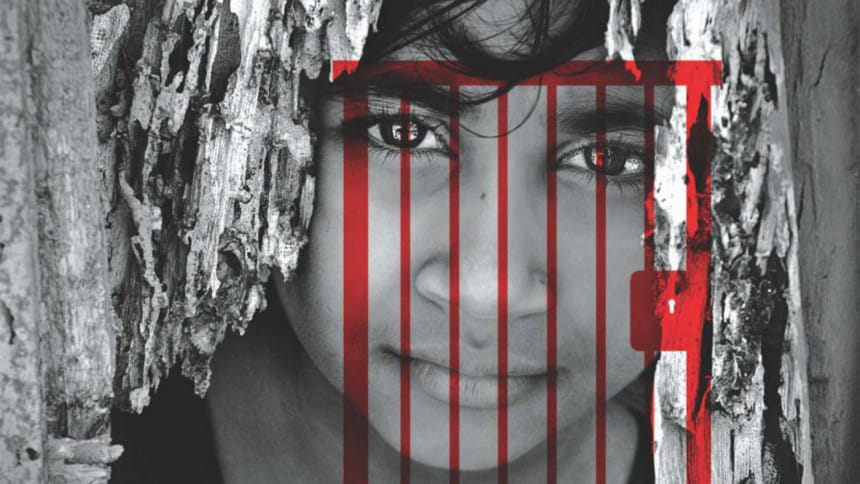

Sexual violence is an emblem of patriarchy in the guise of tradition

A Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics (Banbeis) report from last year suggests that in 2018, girls formed 54 percent of the total number of students at the secondary level. In 1999, it was 43 percent. In another indicator of progress in women's life, maternal mortality has also reduced significantly. According to World Bank, the country's maternal mortality was 434 per 100,000 live births in 2000, which plummeted to 173 per 100,000 live births in 2017. The World Bank data further indicated improvements in female labour force participation, which in 2020 stands at 36.42 percent, up from 24.73 percent in 1990.

While these are successes worth acknowledging, our development is severely hampered by violence against women and girls, especially sexual violence, which has intensified in recent times. According to an estimate of Bangladesh Mahila Parishad (BMP), sexual violence against women doubled between 2010 and 2019. Let's take the number of rape incidents for example: in 2010, the number stood at 940, which more than doubled to 1855 in 2019. Rape is just one of the many forms of sexual violence women and children are forced to endure every day.

Marital rape, meanwhile, is an unacknowledged form of sexual violence unleashed on women, and unfortunately on girls too. Hundreds and thousands of women are forced to endure rape by their own husbands. And why? Because Section 375 of the Penal Code states, "Sexual intercourse by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under 13 years of age, is not rape."

But why would a girl be married at 13 in the first place? "… if a marriage is solemnised in such a manner and under such special circumstances as may be prescribed by rules in the best interests of the minor, at the directions of the court and with consent of the parents or the guardian of the minor, as the case may be, it shall not be deemed to be an offence under this act." This is clearly stated in Section 19 of the Child Marriage Restraint Act, which fails to specify which scenarios qualify as "special circumstances." So, with no clear indication on what special circumstances mean, our girls remain vulnerable to the curse of child marriage and sexual exploitation at the hands of their husbands, who have been taught that wives are their possessions to do with them as they please, and to whom the concept of consent is alien.

Often these young girls are subjected to forced coitus and sexual perversions, leading to significant damage to their reproductive health, not to mention the mental trauma they endure. The tragic story of 14-year-old Nurnahar, who died in October this year, after suffering from gynaecological complications following sexual intercourse with her 34-year-old husband and subsequent lack of treatment, is a case in point. When the teenager reported that she was suffering from genital bleeding, instead of immediately consulting a gynaecologist, the husband kept having sex with her, causing injury and agonising pain. She was given medicine from a local kabiraj, and only when it was too late did the family decide to seek medical help. The girl succumbed to her injuries. The mother-in-law suggested that she was possessed by demonic spirits which caused the bleeding. Despite being a woman—who must have understood what the little girl would have endured—the mother-in-law chose to overlook Nurnahar's trauma, and instead blamed her for her misfortune. Although the girl's family has reportedly filed a complaint with the local police station, chances of justice being served in this case are slim. She was 14 after all—meaning she wasn't raped by legal definition, even if she was.

There are men—fathers, brothers, uncles, grandfathers, in-laws, cousins, friends, acquaintances, strangers—who inflict sexual violence on girls and women every day. And then there are women—mothers, sisters, aunties, grandmothers, female relatives and friends—who discourage other women and girls from raising their voice against such brutality. It is this systematic suppression of women's voices by their own family and close associates, and sometimes by other women, that is emboldening the perpetrators of sexual violence.

The archaic and myopic definition of rape remains another major enabler of this heinous crime. The definition of rape in our law is confined to penile-vaginal penetration. So, if a man forcefully inserts an object into a woman through the vaginal opening, it would not be considered rape, because it has not been a penile penetration. But we have seen incidents of women being subjected to sexual abuse with objects. And how are those cases classified?

Although the government has increased the highest punishment for rape to the death penalty, it is not expected to result in significant change, as the rate of disposal of rape cases remains extremely low. An Amnesty International report citing data from the government's One Stop Crisis Centre suggests that between 2001 and July 2020, only 3.56 percent of cases filed under the Women and Children Repression Prevention Act 2000 have resulted in a court judgment, and only 0.37 percent of cases have ended with convictions. The Amnesty International report further added, "Local women's rights organisation Naripokkho examined the incidents of reported rape cases in six districts between 2011 and 2018 and found that out of 4,372 cases, only five people were convicted."

While these statistics and realities portray the problems that are enabling sexual violence against women, the bigger problem lies in our perspective.

Sexual violence against women is symptomatic of a patriarchal society refusing to act in its best interest. It is happening because of a lack of empowerment, because in an equitable society, this cannot happen. We are living in a society that, unfortunately, still sees a woman as an object that can be dominated, sexually and otherwise. And it is through this sexual dominance over women that the men in our country portray their power and ego.

And this should be a major concern for the policymakers, because this is a reflection of a fundamental disequilibrium: women's empowerment. The ties between economic growth and women's empowerment merits broader discussion, but suffice it to say, their connection is well-established. If we cannot empower women with sovereignty over their own bodies, how do we hope to give them control over their own destiny and that of the nation?

To truly end sexual violence against women, we have to break the cycle of patriarchy masquerading as tradition. We have to rise above the petty urge of the ego that wants to dominate, not just for vanity or the slogan of an equitable society, but for our own growth as a nation.

Tasneem Tayeb is a columnist for The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is: @TayebTasneem

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments