Maulana Bhashani and The Islam Question

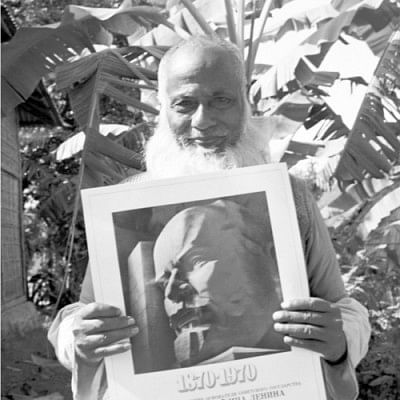

In public discourse, there are two images of Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani: "Green Maulana" and "Red Maulana". The first tries to portray him as an Islamic cleric or pir, and overlooks his lifelong struggle against communalism, authoritarianism and exploitation of the poor masses. The second depicts him as a communist, and ignores the spiritual aspect of Maulana's political ideology. An in-depth analysis of his idea of Islam and its reflection in his political activities can help us understand the true essence of his life and work as well as why he is ever more relevant in the fight against the unholy alliance of authoritarianism and communalism.

Maulana Bhashani's politics was inspired by religion but it never descended into communalism. He had the belief that Islam was the most just religion and, therefore, he found his spiritual fulfilment in the establishment of a just society.

A cursory glance at Bhashani's politico-religious life will illustrate two distinctive traits of his idea of Islam: universalism and liberation of the oppressed.

In his article on the policy of "Rabubiyat" written in the twilight of his life, Bhashani explained his ideology as the undivided equality of all people irrespective of their caste, nationality and religion. Since all human beings are equal before the creator, Allah, the purpose of Islam is to establish a society without discrimination and exploitation, reiterated the Maulana. This spirit of universalism helped him overcome narrow identity politics and embrace common humanity.

Bhashani received religious education at the Deoband Madrasa. His association with progressive Islamic thinkers like "Shaikhul Hind" Mahmud al-Hasan inspired him to join the fight against British imperialism. He actively participated in both the nationalist movement led by Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das and the Khilafat Movement.

Bhashani joined Muslim League in 1930. But he was never a conventional Muslim League politician who invariably toes the party line. He became the president of Assam Muslim League in its Barpeta Session in 1944. At the very meeting, he exhorted the League's General Secretary Muhammad Sadullah, who was also the prime minister of Assam at that time, not to act as a "post box" for the British authorities.

Another story is worth sharing in this regard. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad used to preside over the Eid prayers at Kolkata Eidgah. During the 1940s when the Pakistan demand was garnering wide support from the Muslims of India, particularly from the Muslims in Bengal, Maulana Azad was removed from this honorary duty as he was against the idea of Pakistan and an active member of Congress. Maulana Bhashani was at that time a leading figure of Assam Muslim League. At a public meeting, he criticised this decision with his characteristic sarcasm that Muhammad Ali Jinnah should be appointed as the new Imam.

Bhashani devoted himself to the Pakistan movement. He led the successful campaign during the 1947 Sylhet Referendum through which Sylhet became a part of Pakistan. But soon after the establishment of Pakistan, Bhashani along with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and others formed Awami Muslim League to protest corruption and discrimination by the Muslim League government. Four years later, he proposed to drop the word "Muslim" from the party's official name to make it a platform for people from all religious backgrounds, and thus the Awami Muslim League became Awami League.

In his effort to empower the oppressed, Bhashani always laid emphasis on organising them and making them politically conscious. He was widely respected as pir. He had many muridans (disciples). Bhashani used his religious appeal to organise them politically. When accepting someone as a murid, Bhashani would insist that he took an oath that he would work as a member of the peasant or labour organisation that he led.

Maulana Bhashani identified private property as the source of exploitation. To him, it is contradictory to the spirit of Islam as, according to the religion, Allah holds ownership over all properties and a human is only a custodian. This is clearly different from the position commonly held by Muslim clerics who believe in Allah's ownership but don't strive for abolition of private property. This brings him closer to the communist ideology that also calls for abolition of private ownership.

All through his political career, Bhashani kept up his two-pronged fight against authoritarianism and communalism. He exposed how authoritarian forces often use religion to create a false identity tension between different religious groups and perpetuate their rule. He was also a staunch critic of those communal forces that, in the name of religion, create divisions among people and thereby serve undemocratic forces.

In today's Bangladesh, when a large number of people are reeling under extreme socio-economic pressure caused by the pandemic, we see the rise of a false debate on the difference between sculpture and idolatry. This is not the problem but the symptom of a bigger problem characteristic of a society founded on extreme inequality, injustice and intolerance. Bhashani rightly identified this problem and proposed solutions to it through a revolutionary interpretation of Islam.

Bhashani had a dream of establishing an Islamic university that would be open to all irrespective of their religious identity. He wanted the institution to be an epitome of Islamic education where universalism and the libertarian spirit of Islam would be taught. He believed this kind of education would attract people from all over the world and establish the glory of Islam as a harbinger of peace and prosperity. Will the dream of Bhashani remain unfulfilled?

Shamsuddoza Sajen is a researcher and journalist at The Daily Star.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments