A History of the Destruction of Knowledge

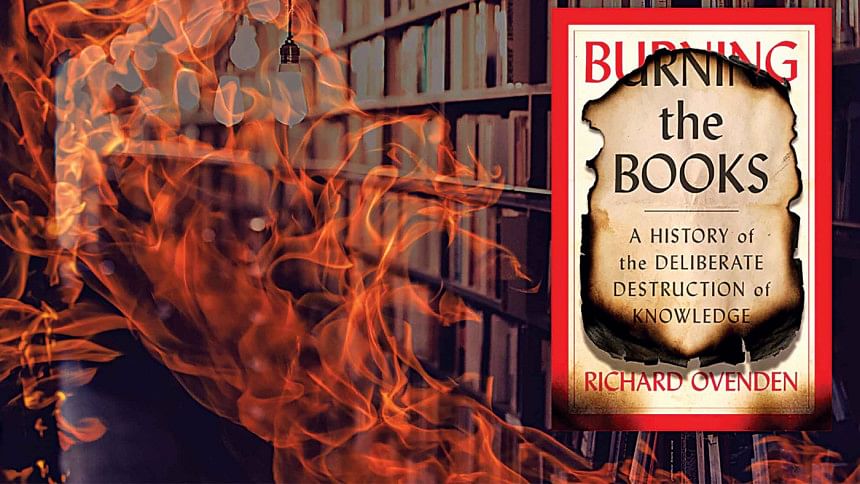

Humanity has always had an ambivalent relationship with knowledge. While the written word has changed from being recorded on papyrus to tablets, scrolls, ink-ridden bindings to printed books all the way to electronic screens, it has been handled apprehensively by power structures, if only for its impact on societies and individuals. Consequently, book burnings have featured recurrently in the discourses of nation-states and empires: Nazi burnings of texts written by "un-German" authors—homosexuals, socialists, and of course Jewish writers—in Germany are among the most infamous examples. Richard Ovenden's Burning the Books: A History of the Deliberate Destruction of Knowledge (Harvard University Press, 2020) is a vivid catalogue of the destruction of libraries and archives, purges of librarians and intellectuals, self-censorship, and the current threat posed to knowledge by a handful of big data firms.

A librarian at the famed Bodleian Library of Oxford University, Ovenden begins with the famed Library of Alexandria, the story of whose destruction remains shrouded in mystery, and its role in the tug of war between pagan, Christian, and Muslim rules. In striking yet easy prose, he writes of the famous Paper Brigade whose members risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jewish cultural items from extermination. Another interesting chapter is devoted to the burning of the National Library of Bosnia, whose multicultural staff fought against the exclusivist Serbian militia intent on destroying what they perceived to be the remnants of Muslim presence in Europe. Countless libraries, mosques, and tombstones were destroyed in this quest to extinguish Muslim heritage from the continent. But being largely Eurocentric in many ways, only one and a half pages are devoted to the burning of the famous Jaffna Library in Sri Lanka and Shia Zaydi libraries in Yemen by Sinhala-Buddhist and Salafi Muslim extremists respectively, who expunged centuries of rich historical traditions of learning and scholarship. Similarly, there are no mentions of book burnings and execution of intellectuals in China, India, or Bangladesh.

What makes the book worth reading and contemplating is the brilliant canopy of stories of known and unknown librarian heroes, their losses and rescues. We learn of Derviš Korkut, a Bosnian Muslim librarian who smuggled an illuminated manuscript called Haggadah out of Sarajevo during World War II, when Jewish documents were being destroyed across Europe.

These anecdotes underline the importance of archives and libraries as vehicles of memory, cultural identity, and reconciliation of history. He argues that archives need to be preserved in order for people to come to terms with themselves and navigate crossroads into their past and the future. For instance, despite being at the threat of destruction, archives played an important role in reconciliation in South Africa after the end of apartheid, when pundits predicted an all-out civil war. In countries like Iraq devoured by sectarian strife, archivists and librarians can help people understand how current and past rulers played a role in pushing the nation to its brink.

Offering fascinating case studies of Franz Kafka, who wanted his best friend to burn his books, and Sylvia Plath, whose journals and diaries were destroyed by her husband, Ovenden then delves into the contested ideas of self-censorship and legacies of the knowledge of geniuses. An interesting case is highlighted with the story of the great rabble rousing poet, Lord Byron, whose physical excesses in life became the source of gossip and scorn, which encouraged his publishers and friends to take the "ultimate curatorial decision to save his reputation by destroying his memoirs".

"Preservation should be seen as a service to society, for it underpins integrity, a sense of place and ensures diversity of memory," Ovenden writes. Encompassing 3,000 years of history from Nineveh to Alexandria to London to Washington DC, Berlin, and Baghdad, Ovenden makes a case for the preservation of knowledge and its intrinsic value in constructing and moulding the history and future of humanity. Yet he expresses his concern over the control of personal data by large tech firms today, and how knowledge is being increasingly atomised in the hands of the few.

Israr Hasan is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments