President of the Poor

He is the "president of the people", more precisely the "president of the poor people".

This is what the then UNDP chief said when conferring the Human Development Award in 2004.

The first Human Development Award, after its introduction two years earlier, was given to Fernando Cardoso, President of Brazil. It provided a general idea that the award was meant for politicians, presidents or prime ministers. Names of presidents and prime ministers came in the list of nominees for the award which is given every two years. But in his speech during the second awards ceremony in 2004, the then UNDP chief said that this particular awardee had made more significant contributions to human development than the presidents or prime ministers nominated that year. That's why the award went to the man who was not president of any country, but "president of the people". This man was none other than Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, founder of BRAC, the largest non-governmental development organisation in the world.

This December 20, 2020 marked his first death anniversary.

This writer happened to have the opportunity to pass considerable time with this legendary man when he was alive. One morning in the winter of 2005, we set out for Sylhet in a car. He had just received the Human Development Award a few days ago. It was officially handed over to him in New York. During our journey, Fazle Hassan Abed told me how he was chosen for the award. It took a number of questions to get this simple answer from him. He had a habit of speaking less about himself. I had been on such journeys with him on several occasions before. We had been to many places together, to Manikganj and North Bengal. The journey to Sylhet was part of my endeavour to write the book Fazle Hasan Abed O BRAC.

The car was moving, and I was getting answers that were shorter than my questions.

"All my experiences of going to many places with you may not be covered in one book. But I will write about them sometimes," I told him. He replied with his characteristic soft smile, "After I die?" I could not answer him immediately. After some moments of silence, the car carrying us stopped at a BRAC office near Narsingdi. The stopover was sudden, not part of our itinerary. A BRAC employee greeted him, saying, "How are you, Bhai? You came after a long time."

At another sudden stopover at a BRAC hatchery, a group of employees rushed forward. "Bhai, you don't visit us as often you did before," one of them said. During another stopover at a BRAC poultry farm, the security guard kept him waiting for two minutes to confirm his identity. Then an official who came rushing toward us rebuked him for not letting his car in. When he got down, a female sweeper approached him with a broom in her hand and said, "Are you well, Bhai? You have forgotten us. You don't visit us nowadays."

These random conversations during the three stopovers show how his employees viewed him.

Fazle Hasan Abed received most of the world's prestigious awards except the Nobel Prize. His knighthood added the word "Sir" before his name. But to all his BRAC employees, he was simply "Abed Bhai".

During these interactions at the stopovers, he politely replied their salaams, calling them by their names, and wanted to know how they were doing, whether their children studied in BRAC schools, and if they were properly using the microcredits of BRAC. He enquired the officials about their targets and achievements. He asked the officer who rebuked the guard why he did so instead of thanking him for doing his job.

Some questions came to my mind observing the incidents, and he answered those during our journey.

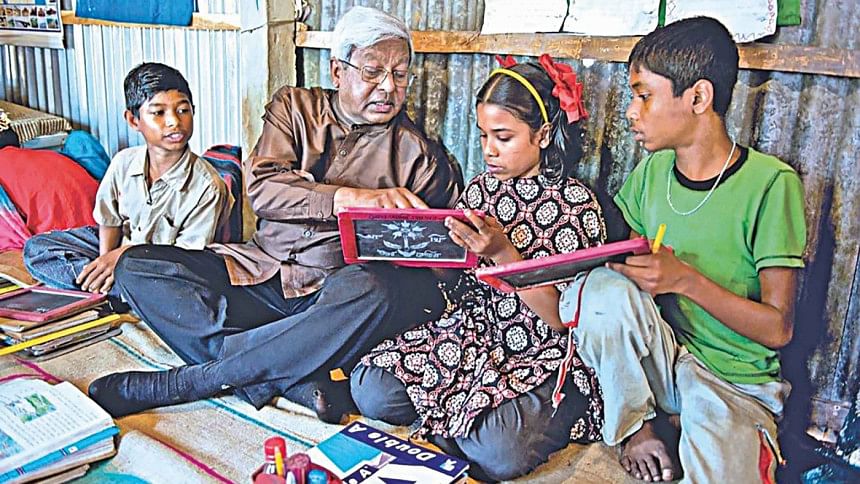

Fazle Hasan Abed used to visit Sullah in Sylhet for seven days every month during the first 10 years of BRAC's activities. He used to visit most BRAC offices on his way. He talked to the employees directly, without making any difference between high and low levels of officials. He often said that he had learned a lot by talking to poor people. He knew most of his employees by their names.

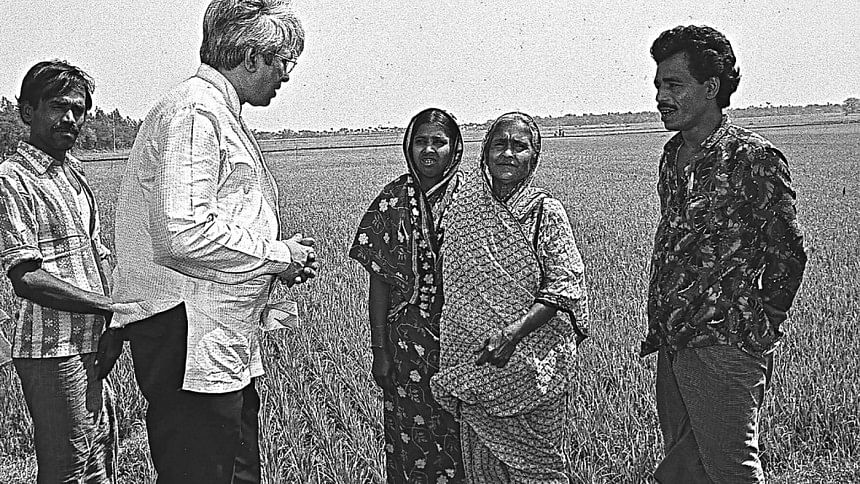

I visited BRAC's offices in North Bengal with him to find the same answers. I saw how female workers easily came to him and talked to him as if he were their own brother. Fazle Hasan Abed had deep faith in the capacity and responsibility of the women. "Our women can quickly cross canals with a pitcher filled with water in one shoulder and their children in the other. So there's nothing that they can't do," I've heard him saying many times.

"It's very important to set goals for a job. Once the goal is set, it helps the employees become efficient and hardworking to achieve the goals. We've been following this policy since the beginning of BRAC," he once said in his typical soft voice.

"If a poultry farm or hatchery doesn't become self-sufficient, they cannot survive. Therefore, it's important to keep in mind the targets and the accounts of profit and loss. These accounts can provide an overall idea of how they are performing," he said.

By the time we reached BRAC's tea garden in Sylhet's Habiganj, it was getting dark. After dinner we sat on the veranda of the bungalow and chatted till late night. This time, Fazle Hasan Abed went beyond his characteristic short replies and talked at length, even without needing questions to nudge him.

He expressed his feelings of being hurt by seeing the life tea workers were forced to lead. Their children are malnourished and sick. There is no opportunity for their children to study. BRAC set up a school for the children of the tea garden, but much more needed to be done, he said.

He spoke of his London life. Throughout our conversation, he mentioned about his friend Marietta again and again.

On our way back the next morning, he seemed to be thoughtful. When I asked, he replied, "Talking about BRAC is bringing back memories of a lot of things in the past. I have never looked back at our past activities before. I have been too engaged with BRAC to do so." He particularly talked about two incidents which, in his words, are as follows:

"In May 1971, I decided to move to London. I was then heading the finance department of the Shell Oil Company. I went to Islamabad from Dhaka and was caught by ISI. I was released two or three days later. Today we walk in the roads of an independent country. But the days of 1971 were tough. At that time, if you wanted to go abroad, you needed to take permission from the Pakistan military government. It was very difficult, sometimes impossible. In case of travelling without permission, you would have to go to Afghanistan which was tougher and risky. Moving to India was easy. But for me, it was important to go to London. From there, I could contribute more. I chose the path of extreme risk. I took a taxi from Islamabad to Peshawar, beginning a journey to the unknown. I reached Peshawar in four or five hours. It was evening then—quite like the time we reached this tea garden. I stayed the night at a hotel in Peshawar. In the morning, I took a bus to the Khyber Pass border. I entered Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass border showing my passport. Upon reaching there, I felt relieved. I went to Jalalabad by a bus, and took another bus from Jalalabad to Kabul. I checked into Hotel Kabul. I didn't have much money with me, still I decided to stay in an expensive hotel for security. I sent a telegraph to London for my ticket and then went to London. There I started working for the Liberation War. I have never taken a break since then, never got tired. It always appeared to me that more needed to be done."

The second incident also involved another journey. In his words:

"In 1974, I learnt about a terrible famine at the Raomari upazila of Kurigram. Oh, the experience I had while going to Raomari!

First, Dhaka to Rangpur. It was night when I reached Kurigram from Rangpur by train. I managed to spend the night inside a shop that night. It was raining heavily. In the rain, I couldn't sleep, rather got soaked like a crow. The night seemed never-ending, a few hundred hours long. Our way to Raomari was via Chilmari. But there was no way to reach Chilmari. After many attempts, I managed to reach Chilmari in the car of a Thana Circle Officer. From Chilmari, the road ahead was through river. There was no arrangement as well. So I managed a speedboat, but it left me at Astamir Char. In Astamir Char, there was no means to go to Raomari. Finding no other way, I started walking in the dark of night. I didn't know if I was going in the right direction. Finally, I reached Raomari after walking 17 miles.

I also spent a night in a shop in a village market while I was out on the BRAC's first job in Sylhet's Sullah. I also spent that night sleepless, being soaked in rain. I was 36 then, and it took me another 17-mile walk to reach Sullah at 4am."

Fazle Hasan Abed walked with BRAC all his life. He took Orsaline to every household in Bangladesh. He invented BRAC's own method of pouring chicken vaccine inside bananas which made a significant contribution to the prevention of poultry diseases. Avoiding the policy of importing poultry feed, he increased maize cultivation by encouraging farmers and produced poultry feed from maize. He took the initiative to produce hybrid seeds in the country by bringing experts from China. He established Arong to provide more employment opportunities to the rural women. He tried to prevent iodine deficiency in the country by producing iodine-rich salt. He contributed to every possible sector to improve the living standards of the people of Bangladesh.

"I will not venture to do what I cannot. Whatever I do, I will do it well"—this was the motto of Fazle Hasan Abed's life. Based on this policy, BRAC has expanded its operations from Bangladesh to Afghanistan and Africa. Success followed BRAC everywhere it made its mark, leaving no precedent of failure anywhere.

After taking BRAC's operations to war-torn Afghanistan, he realised that he should have done it earlier. There was so much to do in Afghanistan. He had a soft corner for Afghanistan as he visited the country on his way to London in 1971. He didn't believe in regionalism. He did not see people through the lens of border or time. He wanted to do something for the poor people wherever they lived. He repeatedly said, there are so many poor people in India. There is a lot I could have done for them too, but I could not.

When he went to Baniachong, his birthplace in Sylhet, many parents visited him looking for jobs for their children. "We have never had a policy that people from Baniachong or Sylhet would get priority in getting BRAC jobs. Many people from Baniachong found jobs in BRAC, but it happened following the same rules that applied to job-seekers from other districts."

His mother, Syeda Sufia Khatun, was his inspiration to do something for the poor people. His mother died while living in England. After her death, he had lost the urge to return to the country. He had bought a flat in England. He had jobs in England, America, and Canada. But the Liberation War brought Fazle Hasan Abed back to the country. He returned on January 17, 1972. In February, he established BRAC. Selling his London flat at 6,800 pound, he launched BRAC in Sullah, a Hindu-dominated area of Sylhet.

He decided not to own any assets and he never budged from his principle. BRAC has assets worth thousands of crores of taka. Fazle Hasan Abed was not the owner of anything in BRAC's possession. His children do not own them either. The house he lived in was also owned by BRAC.

One man alone has turned BRAC into the largest non-governmental organisation in the world. In return, the world recognised him as a legend.

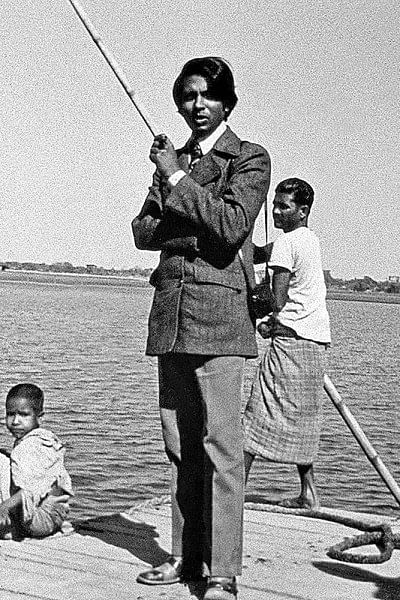

Fazle Hasan Abed was born on April 27, 1936 in one of the largest zamindar families of the country. He lived a colourful life. He and his organisation were well-known all over the world. But there was not much written about him and his organisation. This was the source of my opportunity to come closer to Fazle Hasan Abed.

As a journalist, I had the opportunity to interview him several times. Bichitra editor and freedom fighter Shahadat Chowdhury first introduced me to him. It was in 2002 when I took his interview. After the publication of the lengthy interview, some students from the IBA of Dhaka University came to me to know more about BRAC. Not knowing the answers to all their questions, I directed them to the then BRAC Public Relations Director Tajul Islam. He could not answer all their questions either. Nothing written was found. Tajul Islam said that no one knew these things except Abed Bhai. "If you want to know, you have to talk directly to Abed Bhai," he told them. In the meantime, publishing house Mowla Brothers' head Ahmed Mahmudul Haque one day urged me to write a book on Fazle Hasan Abed and BRAC.

I managed an appointment and met Fazle Hasan Abed. I told him about the lack of information about BRAC and him—the lack of a written history of the formation of BRAC. He listened patiently. Then he said: "We have worked for the people, and we still are. The people of the country know BRAC through its work. Some people may know me through the work of BRAC. People outside the country acknowledged BRAC's work by watching our activities. Students will know about BRAC by seeing the activities. They would learn about BRAC by knowing what BRAC does. But I have never thought that it is our responsibility to inform people in writing what we are doing. I don't see any reason for that."

My reply was: "You are the son of a zamindar family, you went abroad to study, played a role in the Liberation War, and you built such a big organisation like BRAC. Simply put, BRAC's struggle for securing its present place must not have been so simple. Will there be no recorded history of this journey? Ask anything about BRAC and everyone says, Abed Bhai knows. In your absence, that history may end up getting distorted, if not kept in a written form."

After some moments of silence, he said quietly, "All right. I will think about it."

It took him several months to think. Then one day he said, "Okay. I'll talk."

So he agreed to talk. The problem was getting his time. In Dhaka, in the midst of so much work, it was not possible to talk continuously. So it was decided that we would talk while going outside Dhaka. Our talks on numerous occasions over a span of three years finally resulted in the book "Fazle Hasan Abed O BRAC".

Golam Mortoza is a journalist at The Daily Star. He is also the author of the book titled Fazle Hasan Abed O BRAC

This article has been translated from Bangla by Anwar Ali, Staff Correspondent, The Daily Star

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments