How Biden can restore multilateralism unilaterally

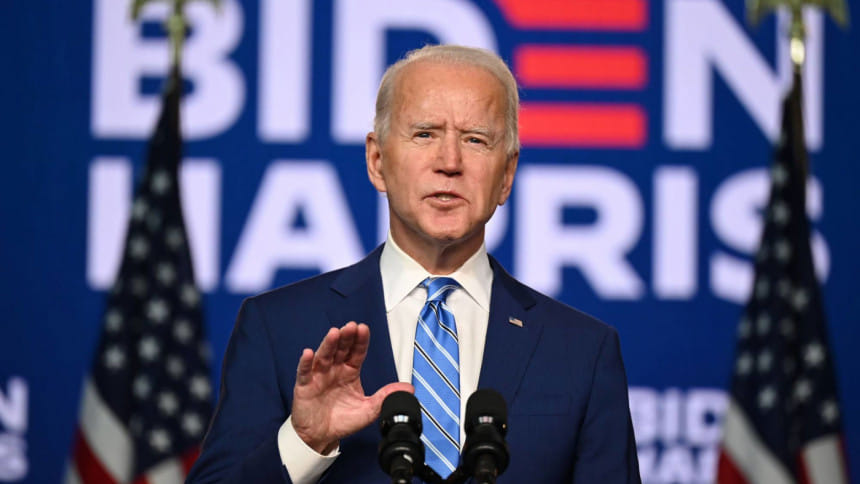

There is so much to celebrate with the new year. The arrival of safe, effective Covid-19 vaccines means that there is light at the end of the pandemic tunnel (though the next few months will be horrific). Equally important, America's mendacious, incompetent, mean-spirited president will be replaced by his polar opposite: a man of decency, honesty, and professionalism.

But we should harbour no illusions about what President-elect Joe Biden will face in office. There will be deep scars left from the Trump presidency, and from a pandemic that the outgoing administration did so little to fight. The economic trauma will not heal overnight, and without comprehensive assistance at this critical time of need—including support for cash-strapped state and local governments—the pain will be prolonged.

America's long-term allies, of course, will welcome the return of a world where the United States stands up for democracy and human rights, and cooperates internationally to address global problems like pandemics and climate change. But, again, it would be foolish to pretend that the world has not changed fundamentally. The US, after all, has shown itself to be an untrustworthy ally.

True, the US Constitution and those of its 50 states survived and protected American democracy from the worst of Trump's malign impulses. But the fact that 74 million Americans voted for another four years of his grotesque misrule leaves a chill. What might the next election bring? Why should others trust a country that might repudiate everything it stands for just four years from now?

The world needs more than Trump's narrow transactional approach; so does the US. The only way forward is through true multilateralism, in which American exceptionalism is genuinely subordinated to common interests and values, international institutions, and a form of rule of law from which the US is not exempt. This would represent a major shift for the US, from a position of longstanding hegemony to one built on partnerships.

Such an approach would not be unprecedented. After World War II, the US found that ceding some influence to international organisations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund was actually in its own interests. The problem is that America didn't go far enough. While John Maynard Keynes wisely called for the creation of a global currency—an idea later manifested in the IMF's Special Drawing Rights (SDRs)—the US demanded veto power at the IMF, and didn't vest the Fund with as much power as it should have.

In any case, much of what Biden will be able to do in office depends on the outcomes of run-off elections for Georgia's two US Senate seats on January 5. But even without a willing partner in the Senate, the president has enormous sway over international affairs. There is plenty that Biden will be able to do on his own, starting immediately.

One obvious priority will be the post-pandemic recovery, which will not be strong anywhere until it's strong everywhere. We cannot count on China to play as pronounced a role in driving global demand this time around as it did in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Moreover, developing and emerging economies lack the resources for the massive stimulus programmes that the US and Europe have provided to their economies. What is needed, as IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has pointed out, is a massive issuance of SDRs. Some USD 500 billion of this global "money" could be issued overnight if only the US Secretary of the Treasury would approve.

Whereas the Trump administration has been blocking an SDR issuance, Biden could give it the green light, while also endorsing existing congressional proposals to expand the size of the issuance substantially. The US could then join the other wealthy countries that have already agreed to donate or lend their allocation to countries in need.

The Biden administration can also help lead the push for sovereign-debt restructuring. Several developing countries and emerging markets are already facing debt crises, and many more may soon follow. If there was ever a time when the US had an interest in global debt restructuring, it is now.

For the past four years, the Trump administration has denied basic science and flouted the rule of law. Restoring Enlightenment norms is thus another top priority. International rule of law, no less than science, is as important to the US's own prosperity as it is to the functioning of the global economy.

On trade, the World Trade Organization offers a foundation upon which to rebuild. As of now, the WTO order is shaped too much by power politics and neoliberal ideology; but that can change. There is a growing consensus in support of Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala's candidacy to serve as the next director-general of the WTO. A distinguished former Nigerian finance minister and former vice-president of the World Bank, Okonjo-Iweala's appointment has been held up only by the Trump administration.

No trade system can function without a method of adjudicating disputes. By refusing to approve any new judges to the WTO's dispute-settlement mechanism to succeed those whose terms have retired, the Trump administration has left the institution inquorate and paralysed. Nonetheless, while Trump has done everything he can to undermine international institutions and the rule of law, he also has unwittingly opened the door for improving US trade policy.

For example, the Trump administration's renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement with Mexico and Canada largely did away with the investment provisions that had become among the most noxious aspects of international economic relations. And now, Trump's Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer, is using the time he has left in office to call for "anti-dumping" sanctions against countries that give their companies an advantage by ignoring global environmental standards. Considering that I included a similar proposal in my 2006 book, Making Globalization Work, there now seem to be ample grounds for a new bipartisan consensus on trade.

Most of the actions I have described do not require congressional action and can be carried out in Biden's first days in office. Pursuing them would go a long way toward reaffirming America's commitment to multilateralism and putting the disaster of the past four years behind us.

Joseph E Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate in economics and University Professor at Columbia University, is Chief Economist at the Roosevelt Institute and a former senior vice president and chief economist of the World Bank. His most recent book is People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent (Penguin, 2020).

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2020.

www.project-syndicate.org

(Exclusive to The Daily Star)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments