A Bangladeshi Babu Like No Other

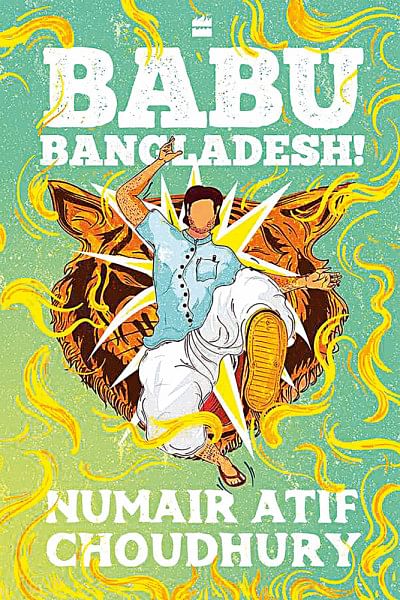

Numair Atif Choudhury's Babu Bangladesh is a tour de force of a novel. Exuberant, extravagant, learned, zany, ingenious, whimsical, irreverent and provocative, this is a work of amazing merit. Though only 402 pages, it resembles somewhat bigger novels like Tristram Shandy and Moby-Dick, works of irrepressible imaginations that resort to what appears at times to be the fantastic but are books grounded in situations and people we can identify with. Salman Rushdie Midnight's Children will come to mind in this context as well.

Numair's "Babu" is the "Bangladeshi everyman" (How many of us Bangladeshis males are called thus even if we had other nicknames?). He resorts repeatedly to the magical realist mode since "there is little separating the fantastic from the quotidian in Bangladesh." Then too "Babu-truth" is "elusive." Obviously, Numair can be whimsical and his tone wacky. But there is method in the narrator's claim about "the Tecumseh" (read "Tamasha!") that is Babu, for wouldn't someone glancing at parts of Bangladesh's history from August 15, 1975 onwards find things at times to be quite bizarre?

The opening episodes of Babu Bangladesh tell us it is about Babu Abdul Majumder. Born in 1971, he apparently became famous from 2008 onwards only to disappear in 2021, heading, we are told, for "unknown skies" then. The narrator is a huge fan bent on reviving the reputation of this "spirited environmentalist." The novel, purportedly, is the result of 9 years of sifting through "rubble to retrieve what is Babu Bangladesh"; it's based supposedly on extensive research into history and gleanings of "Babu's secret writings." The narrator claims to have "chanced upon Babu's private diaries in 2025," almost "three years" into his "research on the book," a gift from a fishmonger admirer of Babu. And when did the narrator finish writing his book? Tellingly, the opening pages, a preface in all but name, signs off thus: "16 December 2028."

The first section of Babu Bangladesh tracks Babu's coming of age. Called "Building," it is framed by Louis Kahn's stunning parliamentary complex. In Numair's telling, Kahn's ambitious structure embodies the expectations of a liberated populace wanting to set the country on the route to greatness after December 16, 1971. But the next few parts of the book track his disillusioning descent into a world of "cloak-and-scimitar" politics, "nepotism," "bureaucratic greed," "embezzlement of funds" and, ultimately, environmental degradation.

Babu grew up though happily in his parental bungalow in Tangail, not far away from a forest that would soon be denuded. In no time at all, we are in a land of "warring…private armies...religious minorities…driven from their lands…largescale looting and fortunes stolen." It is a "dog-eat-dog" world for the young boy, a world of assassinations, coups, counter-coups, and of dreams turning sour. Democracy, socialism and secularism evaporate as nationalism prove to be the one rallying cry to survive from the desecration of the other 3 of the "4 pillars" of the 1972 constitution. A few of the young turn to drugs; a handful like Babu take refuge in fantasies evoked by Kahn's masterpiece. The only salve for those nursing the wounds and traumas of post-independence Bangladesh seems to be through seeking divine clues for the future in Kahn's geometric marvel.

In 1994 Babu becomes a student of Dhaka University when it is "a bouquet of agitations." Here and elsewhere Numair (or his narrator, if one wants to excuse him) generalizes and exaggerates in depicting the extent of the malaise afflicting the university, symptomized for him only in its "session jams,'' dysfunctional student politics and inept administration. Indeed, he seems to have dyspeptic notions about the politics of the country at this stage, now that Islamist parties too had joined in the fray. Desperately and somewhat perversely, Babu joins the Jatiyo Samajtantric Dal (JSD) in 1994, seemingly because it was still dedicated to the 4 founding "pillars" of the constitution and was not marred by big party politics. But Babu is soon disillusioned by the party—it too is part of a world of "broken promises and deceptions." At one point we are told that terrorists are plotting to destroy Kahn's showpiece of democracy itself. The narrative resorts again and again thus to the fantastic and grotesque. The traumatized narrator at times strays into a moral wilderness that makes him wonder why he has been working at a "shameful book and washing national laundry in public" (119). Babu, however, is fortunate to have met an elderly "dowager" called Boro Ma at this point; she tells him unequivocally: "do not ever give up hope" (118). Still, at the end of the first part, he flees the capital to be away from the capitol edifice that had once inspired him so.

The second section of Numair Choudhury's book, titled "Tree," is inspired by the banyan tree outside the Arts Building of Dhaka University. It was, of course, the focalizing symbol of the student movement for Bangladesh till March 26, 1971—so much so that the Pakistani army felt that it had to destroy it during its murderous "Operation Searchlight" assault on the campus. In a novel conceived in the magic realist mode, Babu's parents had first met and then "cheered the hosting of the first Bangladesh flag in front of the perennial on 2 March." The narrator describes myths that had grown around the tree and makes up a few of his own, in the process registering his "Ogygian fascination with trees." Like Tristram Shandy and Moby Dick, the book is given to learned digressions; we thus have one on "Dendranthropology." It then offers readers a five day-by-day militaristic account of what happened after March 26, spicing history with tall tale-flavored passages. This part ends with the union of the parents underneath the tree; that, we are told, would lead to the birth of Babu Bangladesh nine months later!

The tone of Babu Bangladesh, however, darkens in its third section, titled

"Snake." Here Babu enters politics after having left Dhaka in 1999, fearing Islamic extremist attacks. But at the outset he is cautioned against the perils of the route he has chosen; as a friend tells him— "There are too many Babus already; every division has a Babu politician." He stands for election from a constituency in Madhupur, part of Tangail. The location allows Numair to bring into focus his environmental concerns, for what was a lush-green forest sustaining the indigenous population as well as animal and plant life in an area that "teemed with a deciduous biodiversity" is now threatened by official or unofficial encroachments and illicit exploitation of nature's resources. In his new incarnation, Babu at first adopts fiery rhetoric as a populist standing up for those who were destroying the environment and marginalizing the first peoples of the land. He says he has plans "for a revamped national park and global tourism" that soon attract activists like "George Clooney, Gayatri Chakravarti Spivack, the Dalai Lama" and even Arundhati Roy! Unfortunately, he runs foul of the armed wings of the administration as well as government officials who have their own ideas about using the forest.

But then Babu himself changes, taking over parts of the land illegally and reneging on his promises to the settlers, though he has nightmares about a snake asphyxiating him. He survives such traumatic moments only to put on the garbs of a conservationists, thereby winning applause and attention. But the section ends with the narrator torn between blaming Babu and defending him; could it be that he was more a "tool" of others than a "wielder"? Then again, he muses, "in the arsenic green of Bangladesh, who knows what shape truth will take?"

Section 5 of Babu Bangladesh takes us to the Bay of Bengal. We are there because Babu is now thriving as an independent member of parliament who has also been made Adviser of Environment and Forest by a Caretaker Government! The trajectory of this "Babu" is obviously as unpredictably predictable as before. Or as the narrator points out in the opening pages of this last section, "In its elements, this is a story that is as indecisive, capricious and shilly-shally as water." Babu now brings order out of chaos, becomes a celebrity among the "young jet set of Dhaka," enters into a relationship with an attractive woman, and works an "overnight" miracle in an island as he did in Madhupur. But "corruption and bloodletting" devastate the island as it did the forest once; it disappears unaccountably.

So does Babu, the narrator tells us at the beginning of Section 5, titled "Bird," sometime in November 2021, managing somehow to elude his "narrative frame." The three epigraphs of this section are telling, but for reasons of space here I can only quote the last one from Lalon, "O mind, you are a bird encaged! Of bamboo/is your cage made, but it too will one day crash." Somehow he has managed to transcend the "profane and mundane wrinkles of worldly attachments!" The Sufi tradition is invoked, an alternative to the fundamentalist shadow stalking the land.

Almost at the end, the narrator wonders "… Was Babu, still in his forties, truly ready to leave this world?" Uncannily, Numair Atif Choudhury himself left this world, aged forty-six, reportedly accidentally, having drowned in a lake in Japan while taking a walk along its banks. The inside back cover tells us that Numair died before completing the final draft. I felt when I finished Babu Bangladesh that he would have perhaps stretched the last two parts of the five-part novel a bit more if he had another go at it. Certainly, I would have enjoyed being with him for a longer time for his lively prose and imaginative exploration of our country's past, present and future. With Babu Bangladesh Numair aimed, clearly, to write a national comic epic of sorts in prose, albeit in English. It made me feel when I finished reading it—what a loss his death has been for Bangladeshi writing in the language!

Fakrul Alam is UGC Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments