Testimony to the Cruel Birth of Bangladesh

During the tumultuous period of 1971, there was quite a bit of gossip in Washington where all anyone heard about Bangladesh was the phrase "blood, butcher and kill." Archer K Blood was the American Consul General in Dhaka, Scott Butcher was his political officer, and Andy Killgore had left Dhaka just before the 1970 general elections and was working at the US State Department. This anecdote was shared by former Finance Minister Abul Maal Abdul Muhith, who was then posted at the Pakistan Embassy in Washington.

Following the March 25, 1971 military crackdown, Archer Blood and his colleagues at the Dhaka Consulate continued to relay details of the massacre of unarmed Bengalis by the Pakistani junta to Washington and urged the US government to put pressure on the West Pakistani government to stop the killings and go for political settlement.

Denouncing the US policy, they wrote in their famous 'dissent cable': "Our government has failed to denounce the suppression of democracy. Our government has failed to denounce atrocities. […] Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy."

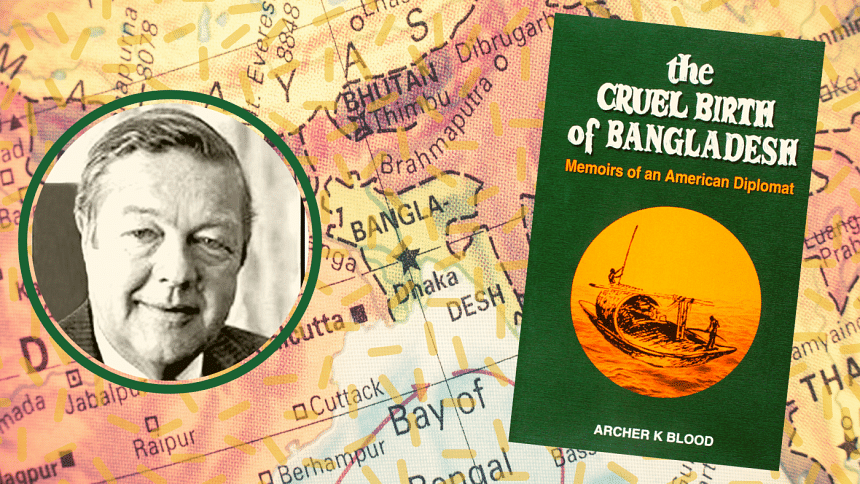

These fateful events are aptly captured in the memoir by Archer K Blood, The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh (The University Press Limited, 2002). The book spans from March 1970, when Blood arrived in Dhaka as American Consul General, to June 1971, marking his withdrawal from the Dhaka office. "It portrays exactly what my staff and I were thinking and reporting during the Bangladesh crisis," writes Blood. In his characteristic integrity and truthfulness, Blood recorded his insightful predictions on the unfolding crisis as well as some mistakes in his judgment.

In an evaluation of the consequences of military crackdown, Blood communicated to Washington that: "Because of unforgettable atrocities of past several days, future course of action likely to be pursued by remnants of 'defunct Awami League' is one-point program: complete separation from West Pakistan. […] India is viewed as mutual ally; considerable pressure will be brought to bear on Indians to provide arms and sanctuary for 'Liberation Movement'."

His prediction was met with deafening silence from Washington. Reflecting on this in his book, Blood writes, "Less credence was being given to our reporting than to the Pakistani claims that little more was involved than a police action to round up some 'miscreants' led astray by India." However, history proved Nixon and Kissinger—who were then at the helm of the US foreign policy-making body—wrong, and Blood's prediction about the ultimate outcome of the Bangladeshi liberation struggle was vindicated. Blood's insider account of the American government's responses to the crisis brewing in Bangladesh reveals the futility of the Nixon-Kissinger diplomacy at the time.

Blood's diplomatic training reflects in his writing: pertinent details of every event, written in clear and concise language, and supported by excellent judgement. Thusly the book sheds lights on many little-known events of the 1971 war. One such incident was that the American diplomat in Dhaka had to made a diplomatic call at near-gunpoint. Since the crackdown Blood had been stubbornly refraining from calling on General Tikka Khan, the Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA) of the East Pakistan. On April 2, when he was leaving office a Pakistan army captain stopped him and informed that the CMLA wished Blood to call on him at his residence at 6pm that evening. Blood had to make the visit and he writes about it in a nonchalant tone that the 45-minute conversation brought out nothing more important than his offer to be of any assistance to him and the American community. "The next morning, as I had expected, the controlled press carried a front-page story that the American Consul General had called on the Chief Martial Law Administrator," quips Blood.

I want to highlight another brilliant observation made by Blood on the lives of the two leaders, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Bhutto, whom he closely observed through the unfolding of the crisis:

"There are obvious similarities between the lives of Bhutto and Sheikh Mujib. Both were indispensable to their people at a crucial juncture: Bhutto in the despair following the loss of East Pakistan. Mujib both in the euphoria following the December 1970 elections and the agony following Yahya's military crackdown. […] Their stories are certainly tragic, even chillingly so. But at the same time, they display a courage and strength of personality and a human frailty that seem more than life size. If military rule in Pakistan and Bangladesh has run its course and political government faces a more secure future, then the history of these two countries, and history is written by the winners, should appropriately assign Bhutto and Mujib an everlasting place in their respective national pantheons. In any event I feel quite confident that in the afterworld Mujib and Bhutto have more to talk about and share together than either does with Yahya Khan."

Along with such insights and observations, The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh is a rare mix of "intensely felt personal memoir" and a serious account of the Bangladesh crisis which was later dubbed by Kissinger as the most complex and difficult issue to confront in the first Nixon term.

Archer Blood started his career with flying colours. He received the prestigious Harter Award and the Meritorious Honor Award of the US State Department for his service during the cyclone relief operations in Bangladesh. However, his non-conformist views and boldness made the high-ups at the Washington office uncomfortable. The dissenting diplomat was recalled to Washington hastily and his career faltered. Blood went into early retirement in 1982 and joined Allegheny College as a teaching staff. If we look at the academic rigour maintained in The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh, we must say he attained extraordinary accomplishment in this new career. Blood started writing the memoir in 1998. He waited until the telegram and other official documents relating to the event were declassified by the US State Department. He made an erudite use of these archival materials.

Reading through the pages of The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh, a reader can't overlook the compassion with which Blood tried to comprehend the tremendous suffering of the valiant people of Bangladesh during the cruel days of 1971. He responded to the call of conscience and his memoir offers a glimpse of that heroic dissent.

Shamsuddoza Sajen is a journalist and researcher. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments