Finding a new trajectory for education

As we step into the second decade of the 21st century and Bangladesh is poised to become a middle-income country, a pertinent question about the education system may be whether the glass is half-full or half-empty. Many will argue that as far as the nation's education system is concerned, a half-full glass is not good enough, especially as the world faces existential challenges from the global pandemic and a new phase of globalisation and automation.

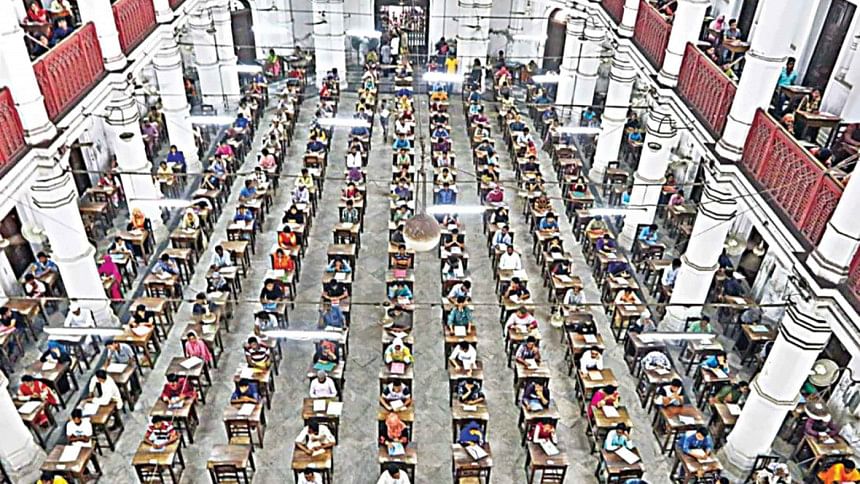

The education system in Bangladesh consists of 40 million students, 200,000 institutions and over a million teachers—one of the largest in the world. There are also non-formal primary education centres and quomi (indigenous) faith-based madrasas enrolling large numbers of adolescents and youth not included in the official education statistics. Primary and secondary level institutions naturally form the bulk of the system with approximately 20 million students in primary education (including Ibtedayee madrasas recognised by government and private institutions); 15 million students at the secondary level (including technical and vocational institutions and government recognised madrasas); and roughly five million in general tertiary education and professional higher education (estimate based on Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics 2019 data).

At the primary level, close to universal enrolment has been achieved, though a proportion of those enrolled still drops out before completing primary school. Gender equality in enrolment at the primary and secondary levels is another accomplishment. Adult literacy rate has reached three quarters of the population over age 15. The country is enjoying a "demographic dividend" with a decreasing dependency of non-working to working age population.

All this is in sharp contrast to the situation five decades ago, at the birth of the nation from the anvil of the Liberation War. Only one out of four children completed primary education then, one out of five adults could read and write, and barely one of 20 young people could participate in higher education. Progress in expanding the school system has been commendable, both for girls and boys, which is an exceptional achievement among developing countries. Could more be done to equip young people with skills, competencies and values necessary for the 21st century?

The coronavirus pandemic has been raging globally for a year and the end is not yet in sight. It has brought us face-to-face with the urgency of figuring out its immediate and longer-term impact. In this setting, the new phase of globalisation and automation emerging from the 4th Industrial Revolution has to be included. How should the trajectory of progress in education change, so that the education system can help the nation face the new challenges and fulfil its aspirations?

Within the limits of a short article, the question about how the system need to change is discussed by examining what may be described as cross-cutting issues of the education system as a whole, rather than looking at problems discretely in various subsectors with a fractured view.

CROSS-CUTTING SECTOR-WIDE ISSUES IN EDUCATION

Various cross-cutting issues, which present both difficulties and potentials for the education sector, have come up in education discourse. These include: teachers' professional competence and numbers; promoting ethics and values through education; implications of climate change and natural and man-made emergencies; ICT for and in education; implications of the 21st century skills and the Fourth Industrial Revolution; serving children with special needs; and promoting inclusive access. Besides these purpose and quality-related issues, there are two other concerns which need attention to deal with the substantive issues—education resource adequacy and education governance and system management.

Teachers: The need to think afresh about attracting and keeping talented people in the teaching profession is recognised as a major challenge for improving education system performance. Bangladesh along with countries in South Asia, unlike other regions of the world, does not have a well-established pre-service teacher education programme. This is so even though school teaching is the single largest field of employment for college graduates. To place a properly qualified and certified teacher in a classroom in front of students as a standard requirement is more an exception than the rule. School teaching is not the first choice as a career for the more talented higher education graduates.

A concurrent professional teacher development approach is the practice in many parts of the world as a step to break the vicious cycle of poor teacher quality and poor student learning. It combines general education and pedagogy in the four-year degree programme, instead of the sequential model which is the pattern in South Asia including Bangladesh. To realise the benefit of the concurrent training approach, it has to be accompanied by other necessary steps. These include enhancing incentives, status and career path of the education workforce. Equally important is to ensure the quality of the concurrent programme itself. A beneficial effect of this move, if properly implemented, would be to show the way for a qualitative change in the colleges under the National University.

Promoting ethics and values in school: As Bangladesh moves up the ladder of development, it has to be kept in view that the true measure of development is not just total GDP or per capita income. The real measure is how people are empowered and their dignity and rights are enhanced. For the education system, it means producing learners who are competent, skilled, purposeful, wise, and equipped to fulfil their own personal goals and their duty to society. They must be capable and willing to make their community and the world a better place. The new generation must be sensitive to the changing global world, accept and respect diversity and the plural human identities.

In the general social environment of declining morality and ethical standards, a hopeful sign is the role that teachers can potentially play—individually and collectively. His/her capabilities, professional competence, and ethical principles can make a difference. Because, they touch the lives of young people in classroom and outside and can be the role model for the young people. This can happen if thinking afresh about the teaching profession can be undertaken.

A study on promoting ethics and values in school in Bangladesh underscored various actions needed on specific areas of school operations and organisation. But there is a common thread of teachers' role and responsibility that ties the proposed actions which comprise: i) a forward-looking and rationality-based approach with a commitment to dignity and rights of all human beings, and acceptance of diversity and plural identities of people; ii) the whole school, its culture and environment, not just the classroom, contributes to cognitive, social, emotional and moral development of students; and iii) school functions and succeeds, not in isolation, but in a social setting in partnership with parents, community and the larger society (Ahmed and Kalam, 2018).

Response to climate change and emergencies: Bangladesh is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to the effects of climate change. Educational institutions are affected by multiple natural disasters, often simultaneously, disrupting children's learning and placing them in danger. Educational development plan, operating plans and budgets must provide for these recurring hazards. Education content and learning activities also need to address understanding and coping with climate change and disaster preparedness. The Covid-19 pandemic, shutting down schools across the world, points again to the critical importance of emergency preparedness and promoting resilience as a necessary theme in the education system.

ICT in and for education: Vision 2021 and Vision 2041 of Bangladesh embracing the Digital Bangladesh agenda envisage application of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in all spheres of development. ICT capacity development of teachers, trainers, curriculum developers, and education managers needs to be improved and be part of an ongoing capacity building programme. Knowledge acquired by training attendees, after they returned to their institutions, need to better apply what they learn and share the knowledge with colleagues. With the spread of ICT resources, real-time monitoring, feedback, and reporting mechanisms can be introduced in education institutions as an education management information system (EMIS). The shutdown of schools due to the Covid-19 pandemic illustrates the role and potential of ICT-based learning.

21st century kkills and the 4th Industrial Revolution (4IR): Life and the livelihoods of the majority of people in Bangladesh are still characterised by the use of the second or even the first industrial revolution technologies. These comprise respectively of augmenting mechanically animal and human muscle power (such as pulling rickshaws) and the use of electric energy in the industrial assembly line. Simultaneously, today most people are into the third industrial revolution through the penetration of mobile phone technology. However, 4IR—a combination of automation, robotics, artificial intelligence, radical change in the nature of work, and innovation in economic production and services—has arrived. It has major implications for education, skill development, employment and entrepreneurship, which must figure in education content and methods, planning and strategies (Schwab, 2016).

Children with special needs: The key element of the principle of inclusive education is that the children with special needs including those differently abled are brought into the ambit of quality education services.

BANBEIS statistics of 2018 show that about 46 thousand children with different types of disabilities were enrolled in government primary schools including 21 thousand girls. These numbers are meagre; and data on access to non-government schools or to secondary or tertiary level education institutions are currently not available.

Inclusion of the disadvantaged: The government spends a large share of its education development budget as incentives for the disadvantaged groups through programmes such as school feeding, different kinds of stipends, and free distribution of textbooks at primary and secondary levels. In recent years, school feeding and stipends respectively have claimed between 10 and 20 percent of the total education sector annual development budget.

With growing household incomes, and need for larger resources in quality enhancing inputs including more and better teachers and better facilities, it is time to re-examine the growth trajectory of incentive spending and how incentives may be more specifically targeted to the disadvantaged groups.

Education finance and resource management: A persistently low level of public investment for education remains a challenge; so is making better use of these resources. Under USD 250 is currently spent by the government per school child. This is slightly over a quarter of what is spent on average in the South Asian region (World Bank, 2019).

Larger resources and budget provisions for improved school infrastructure, school feeding programmes, better learning materials, and more and better paid teachers should result in better learning outcomes. However, the evidence is not unequivocal—it is very much conditional on factors relating to efficiency of resource use, effective management and accountability. It also can be argued that there is a threshold or minimal level of resource inputs that is critical to affect results positively, otherwise the resources and inputs may be wasted.

GOVERNANCE, SYSTEM MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING

Major structural and operational issues in education with significant governance and management implications have come to the fore from studies and public discourse. The structural issues, left un-addressed, impede operational steps to improve system performance. An analysis regarding the structural and operational issues was undertaken, in which this writer participated, to develop an action plan for implementing the Seventh Five-Year Development Plan (PRI, 2017). The action plan remained a draft and was not acted upon, though the issues remain relevant. This is symptomatic of governance weakness. The issues identified were: Resource inadequacy, decentralisation of education governance, effective skills development strategies, quality control in higher education, need for one ministerial jurisdiction for school education, a comprehensive law for education, effective public-private partnership building in education, and establishing a permanent education commission.

Various operational issues arise from the long-standing structural weaknesses and the consequent deficiencies in the governance, management and decision-making process in the education system. These cannot be discussed within the scope of this paper, but some may be mentioned by way of example—student learning assessment, process of curriculum reform, harmful political interference, policy implementation mechanism, use of digital technology, and so on. Important as these are, these need attention in a holistic way, not piecemeal, within a framework of necessary structural changes noted above.

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF EDUCATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The political power structure and dynamics of decision-making have led to continuing reluctance and resistance to addressing the structural and operational problems of the education system noted above. To illustrate the point, school education remains bifurcated under two ministerial jurisdictions; there is silence on the 2010 Education Policy recommendation for a permanent education commission as an oversight body for monitoring education reforms, and there is no visible effort on a unified curriculum and common standards for all children in primary and secondary education. There is the inability to address the dilemma of major public funding support for a parallel system of madrasa education that send millions of young people to a dead end in terms of jobs and life opportunities in a modern society. A comprehensive education law that recognises and fulfils the right to equitable education has not been adopted. Repeated political pledges to raise public spending as a ratio of GDP and promises to decentralise education governance have not been translated into concrete action. New thinking about teachers' professionalism, status, role and means of attracting the best and the brightest into the profession is yet to become a national priority.

The gatekeepers of education, the senior officials and the political decision-makers, have not shown an appetite for addressing the critical issues. They have remained satisfied with managing the status quo. The transformation needed in the education system to meet the challenges of the 21st century cannot be achieved by the status quo.

The existential challenges humanity faces today may result in the end of human life on the planet. The advent of machines that think requires us to imagine work, managing production and services, and organising distribution of income and entitlements in new ways to avert dooming the life and livelihood of millions of people. Coping with these challenges requires how people acquire knowledge, skills and attitudes is revamped and organised differently.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Time is fast running out for decisive climate change action, balancing the needs of the present generation and the future ones. The pandemic, not likely to be the last one, is a tell-tale consequence of human transgression into the sphere of nature and biodiversity. The new form of globalisation driven by artificial intelligence, automation and Internet of Things pose dilemmas about upholding justice, social cohesion and human dignity. Societies and individuals need a moral compass to guide themselves more than ever.

On the 50th year of independence, the nation needs to recommit itself to the founding principles to uphold the aim of a just and progressive society, promoting human dignity and rights for all in unity, while celebrating diversity and multiple identities of people. The imperative now is for the education endeavours to be dedicated to the four fundamental principles of the constitution—the "high ideals of nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularism" and to fulfilling the "fundamental aim of the State to realise through the democratic process a socialist society, free from exploitation, a society in which the rule of law, fundamental human rights and freedom, equality and justice, political, economic and social, will be secured for all citizens" (Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Preamble, 1972). Abiding by these principles and fulfilling the fundamental aim are noble challenges for the education system and for all concerned with education.

Manzoor Ahmed is professor emeritus at Brac University.

End Notes

1. Ahmed. M. and Kalam, M.A., eds. (2018). Ethics and Values in School – Capturing the Spirit of Education, Dhaka: Campaign for Popular Education.

2. BANBEIS (2019). Bangladesh Education Statistics 2019. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics.

3. Government of Bangladesh (1972). The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. Dhaka: Ministry of Law.

4. Policy Research Institute (2017). "Bangladesh Education and Technology Sector Action Plan." Prepared for Planning Commission. Revised Draft May, 2017. Dhaka: General Economics Division, Planning Commission

5. Schwab, K (2016). "The Fourth Industrial Revolution: What it means, how to respond", World Economic Forum, 14 January 2016. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments