Socio-political evils of corruption: Not everything is lost yet

Bangladesh is often mentioned as a development dilemma for its commendable performance in terms of GDP growth and socio-economic indicators on the one hand, that on the other, contrasts strikingly with pervasive corruption and poor performance in nearly every governance indicator. The country's GDP growth has remained consistently high at around seven percent for several years, while in terms of such indicators as Human Development Index (HDI), Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), Gender Development Index, population growth reduction and life expectancy at birth, Bangladesh has performed better than comparable countries in the region of South Asia and beyond.

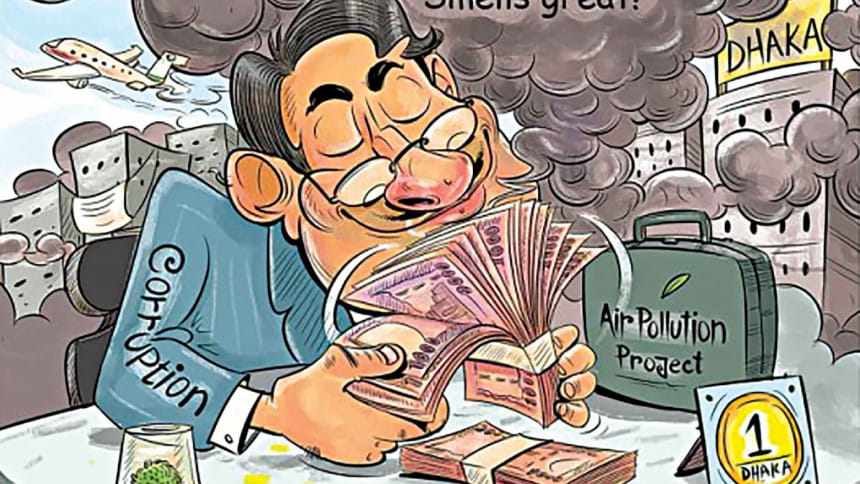

Bangladesh's performance in growth and socio-economic transformation could have been much better if it could achieve higher standards of governance and effectively controlled corruption, the cost of which is as high as 2-3 percent of GDP, as revealed by a former finance minister. Add to this, the skyrocketing illicit financial outflow to the tune of USD 10 billion annually as per credible estimates, not to underestimate the likes of the Canadian Begum Para and Malaysian second home, of which Bangladeshi money launderers are among the leading clients.

In fact, the country has witnessed weaker performance than its South Asian and many other peers in terms of most of the well-known governance indicators. These include the Rule of Law Index (112th out of 126 countries in 2019), Regulatory Quality Index (-0.83 in 2018 on a scale of -2.5 to 2.5), Government Effectiveness Index (-0.75 in 2018 on a scale of -2.5 to 2.5), Political Stability Index (-1.03 in 2018 on a scale of -2.5 to 2.5), Voice and Accountability Index (-0.73 in 2018 on a scale of -2.5 to 2.5), Press Freedom Index (151st in 2020 among 180 countries), Political Rights Index (5 in 2020 on a scale of 7 to -1) and Civil Liberties Index (5 in 2020 on a scale of 7 to -1).

According to the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), Bangladesh continues to be ranked among countries where corruption is perceived to be most pervasive. According to the 2020 CPI report, Bangladesh has scored 26 out of 100, well below the global average of 43, the benchmark for moderate success in corruption control. We are embarrassingly the second worst scorer in South Asia after only Afghanistan, and fourth lowest among the 31 countries of the Asia-Pacific region.

In addition to macroeconomic costs of corruption in terms of loss of GDP as mentioned above, people's sufferings from bribery and other forms of corrupt practices in key sectors of service delivery remain very high. 66.5 percent of the respondents were victims of one or other forms of corruption according to the National Household Survey on Corruption launched by Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) in June 2018. It further showed that more than 89 percent of those who paid bribes were forced to do so because bribery was the only option for being able to access public services—an unbearable daily life burden of immorality of the corrupt.

The government recognises combating corruption as critical to progress towards realising the Perspective Plan - Vision 2021, the successive Five-Year Plans and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Vision 2021 asserts that "the Government is determined to confront and root out the scourge of corruption from the body politic of Bangladesh… (and) intends to strengthen transparency and accountability of all government institutions as integral part of a programme of social change to curb corruption."

As a signatory to the UN SDGs, Bangladesh has pledged to "promote a peaceful and inclusive society… provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels." Implementation of SDGs demands a paradigm shift towards the qualitative compared to quantitative measures of development. Under target 16.5 Bangladesh commits to "substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms"; under 16.4, to significantly reduce illicit financial flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets; and under 16.10, to "ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms." Such lofty commitments as well as the SDG pledges of inclusive society, leaving no one behind, accountable and inclusive institutions and fundamental freedoms, can only be achieved through higher levels of participatory governance and corruption control.

As a State Party to the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) Bangladesh has also promised to "promote active participation of individuals and groups outside the public sector, such as civil society, non-governmental organisations and community-based organisations, in the prevention of and the fight against corruption."

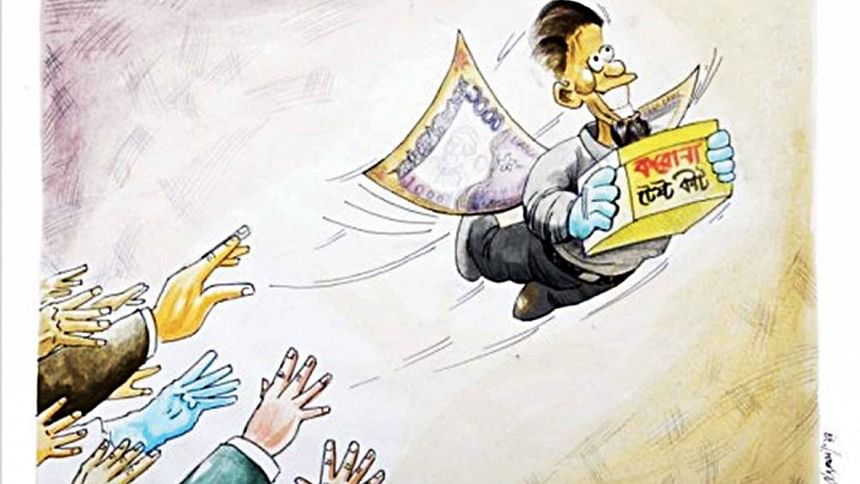

To cap it all up, the ruling party has been very articulate in anti-corruption pledge as per their election manifesto as well as the prime minister's commitment to zero tolerance against corruption repeatedly pronounced in recent times, and specifically reiterated in the coronavirus context. What happens in reality is just the opposite. Corruption has flourished, particularly since the coronavirus crisis began when a section of unscrupulous people, often linked with power, have taken the crisis as an opportunity to abuse power and increase their income and wealth illicitly.

The advent of coronavirus crisis has deeply exacerbated governance challenges in general and with respect to response to the crisis and its fallout. A TIB study launched in June 2020 showed stark deficits in terms of all seven indicators of governance examined—rule of law, preparedness, capacity and effectiveness, coordination and participation, transparency, irregularities and corruption and accountability.

The recovery and stimulus package have been ill-designed and distorted in favour of the powerful and against the underprivileged. Unaccountable use of nationally and internationally mobilised financial resources, especially in procurement, distribution and delivery are accentuating the impact of increased unemployment, poverty, deprivation, vulnerability and inequality in terms of gender, faith, ethnicity, disability, etc. Violations of civil and political rights are becoming acute with accompanying risk of further deficits in governance and governmental trust.

The pandemic has exposed and reaffirmed the infrastructural, systemic and resource deficits in the health system as well as other related sectors like social protection and education which are likely to continue to cause public sufferings including further discrimination, injustice and lack of redress. People are confronting the challenges of reduced and distorted access to public services in health, education, safety nets and the like. There is more micro-level abuse of power and rent-seeking in the troubled waters of deficits and institutional decay, and hence more opportunities for corruption.

It is not unusual in the context that compromise of business integrity and lack of corporate accountability have flourished in geometric proportions. Media and civil society face greater prospect of shrinking space, not to speak of their own institutional and financial crisis. Mobilisation of voice and accountability has become more challenging.

Beyond those unleashed by the coronavirus crisis, Bangladesh confronts greater challenges of governance in many forms. On top are indications of increased concentration of power, followed by reduced space for political dissent and hence shrinking scope of checks and balances and accountable governance. The already dysfunctional institutions are further subjected to partisan political use while low level of law enforcement is leading to reduced access to justice and increased impunity especially for abuse of political and governmental power. Risk has increased about discrimination, especially based on various markers of identity, side by side with increased deficits of social, economic, political, and especially human rights. Increased control and surveillance on information has become normal which is undermining the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of information and opinion.

The silver lining in the form of enhanced scope of digitalisation of public service and more robust flow of information from non-traditional IT-based sources like social media are also under stress by enhanced risk of misinformation flow coupled with the government control on freedom of information. While digitisation is raising hopes, these are also being undermined as limits of benefits of digitisation are also being exposed. Another recent TIB study has shown how the much-hyped E-GP (Electronic Government Procurement) has failed to have much impact in terms of improved governance and corruption control, mainly because procurement continues to be subjected to manipulation by the politically powerful.

In fact, a major qualitative transformation has taken place over the years in our political space. In the first Parliament of Bangladesh the proportion of MPs who had business as their primary occupation was below 18 percent. Rising steadily since then, the ratio has reached 59 and 61 percent respectively in the 10th and 11th Parliament. This does not include indirect beneficial ownerships. People enter politics and assume politically important positions including that of public representatives not by virtue of political participation and experience, but by treating the political identity or position as investment and as designs of profit-making.

Politics has also for long been a zero-sum game where the winner takes all approach is striving to establish monopolistic control of the political space and the spoils that come along. Business and profit-making relationships of public representatives with the government is considered a matter of politically legitimised right. Business, investment, recruitment, public contracting, profiteering, land grabbing, embezzlement, extortion and influence peddling have become the object of a turf-war involving various forms of same-side violence, including deaths associated with a narcotic dependence on corrupt practices for self-enrichment. In a context of collusive abuse of power, corruption has on the other hand become a killer, as witnessed in case of Churihatta or Rana Plaza like tragedies.

Deficit of effective enforcement of the political pledges is considered to be the most important predicament against democratic and accountable governance. The key institutions of democracy and national integrity system—the parliament, executive, law enforcement agencies, administration, judiciary, media, private sector, civil society, and even various professional groups—have been deeply politicised causing low level of rule of law, institutional performance and enforcement of policies and systems. Other cross-cutting issues are no less important, like weak oversight functions, deficits of technically skilled human resources imbibed with integrity, lack of incentives and dearth of professional competence of stakeholders.

Politics and governance are bedevilled by conflict of interest, nepotism and a pervasive practice of collusive non-compliance while the deficit is acute of exemplary punishment of the corrupt which facilitate further governance deficits, corruption and impunity. The ACC continues to struggle to gain the trust of the people. Abuse of power, especially at the high level, is hardly brought to justice. On the other hand, a denial syndrome prevails amongst a section of the powerful who not only react sharply, but also find evil designs and conspiracy against the state when civil society raises voice against corruption.

Even though corruption is already deeply entrenched and institutionalised, its effective control may be still possible. Much of it will depend on how serious our political leaderships are about corruption control. Four mutually reinforcing drivers of effective anti-corruption strategy are indispensable. First is the political will at all levels, not only on paper but in practice without fear or favour. Second, the corrupt must be brought to justice ensuring equality of all before the law, irrespective of the identity and status of the individual. Third, the institutions of the national integrity system must be transparent, efficient, accountable and effective, both individually and collectively. Fourth, conducive environment must be created for people at large, particularly media, civil society, and NGOs to raise and strengthen the demand for accountability and against corruption.

The primacy of politics cannot be underestimated. The endemic malaise of mixing up what is public with what is private, much of it related to the increasing mutual dependence of political opportunity with business and profiteering opportunity, must be treated effectively. The idea of managing conflict of interest is almost absent among many in important public functionaries, whether elected or appointed. We need a legal and operational structure to manage conflict of interest so that a power-holder's private or business interest cannot be improperly promoted by decisions and/or actions taken by using official position. A robust system of conflict of interest management founded on legal and ethical basis would be able to ensure that public interest related decisions are based on merit without regard for personal or group interest, backed up by disclosure of interests and their potential conflict.

A business integrity programme consistent with the National Integrity Strategy is long overdue, with the aim of creating ethical business practices. Collective action against corruption, as in many countries, may demonstrate to the business community that corrupt practices, coercive or collusive, are in the end harmful for all parties involved in business. Business entities and their associations can adopt standards and practices of self-regulation that can motivate stakeholders in the public sector to promote business integrity and stay away from corruption.

Adoption of sectoral and sub-sectoral code of conduct to practice regularly updatable disclosure of "what you earn, where and how you earn, what you pay, and whom you pay" including information on indirect beneficial ownership could go a long way in deterring corruption in the private sector, including money laundering in particular.

Implementation of RTI Act 2009 must be further effective to ensure the people's right to know, especially in relation to what happens to public resources. Where such resources come from, how they are spent and on what basis, etc., are the key questions to which answers must be disclosed proactively and on demand. The perception that some institutions in the public sector like law enforcement and security agencies are exempted from such obligations is unfounded. Information on corruption and human rights violation by institutions included in the so-called exemption list is well within the jurisdiction of the Act.

To ease public harassment in service delivery sectors digitisation and online transactions system must be extensively introduced and robustly practiced. As the corrupt continue to remain unpunished, it not only frustrates the victims and makes them more vulnerable, many honest and heretofore uncorrupt people are forced to take recourse to corrupt practices. Raising voice and demand, especially of the new generation against corruption must be facilitated further if the government is sincere about its commitments. Public resources and capacities should be invested to control corruption, not to control the flow and disclosure of information on corruption.

Effective delivery of anti-corruption demands a retransformation of values, norms and practices in political parties. This retransformation involves the task of delinking political positions and political opportunities from business and profit-making opportunities, as difficult as it may sound. The sooner our politicians realise how badly politics is alienating itself from the people the better for corruption control. Our political leaders need to recognise that it is only in their hands that the Frankenstein of corruption that has been created can be controlled.

Equally important is the task of depoliticising the state institutions, rendered almost dysfunctional mainly by partisan influence. The state structure has been exposed to kleptocratic capture by those who benefit from corruption at the expense of those who would like to control it. In the absence of any real progress to reverse it by re-establishing effectiveness of institutions and primacy of the rule of law, there is no magic bullet to controlling the cancer of corruption.

Iftekharuzzaman is Executive Director, Transparency International Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments