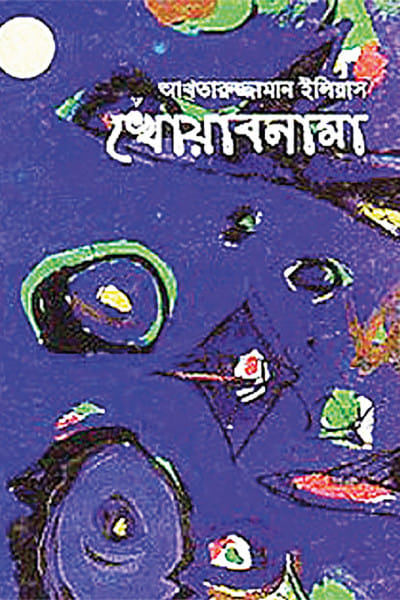

Khwabnama: The Bangladeshi Epic

A few months ago, during the height of the pandemic, my teacher and mentor who is now a UGC professor called me up one morning to convey to me that he has finally finished reading Akhtaruzzaman Elias' novel Khwabnama. His voice exuded both excitement and elation. What he told me afterwards is even more fascinating. He said that Elias' last novel is among the finest he has ever read and should be ranked among the twentieth-century's very best. It took me some time to process what I heard. It was not like I was surprised. I had long held the view that Khwabnama ranks among the greatest Bengali novels ever written and is a classic in world literature. It was, for me, a case of feeling vindicated, for I have heard contrarians claiming otherwise and suggesting that Khwabnama's difficult prose undermines its greatness. Now that a distinguished professor who is among the foremost scholars of our era—one who has researched on novels for more than half-a-century and whose understanding of the genre goes far deeper than anyone I know—has unequivocally espoused similar views about Khwabnama, I feel I should rearticulate some of my earlier views and explain why I think so highly of this 352-page-long work.

Academics who study English literature barely ever show interest in Bengali literature. Except Rabindranath Tagore who has attracted commentators from many different parts of the world, there is hardly any engagement with the vast and immensely rich body of work available in Bengali language. When it comes to Bangladeshi literature produced in Bengali and other languages, the lack of attention is even more telling and visible. While the disconnect between Bangladeshi English departments and Bengali literature is illustrative of these departments' alienation from the nation and culture they are located in, the complete silence in the Bengali departments about an immensely talented and globally acknowledged poet like Kaiser Haq or a writer of the caliber of Zia Haider Rahman is symptomatic of a different kind of prejudice reeking of close-minded linguistic nationalism. I feel time has come for our English departments to shake off their colonial mindset and engage more solidly with the culture and politics of this nation and its people. The colonial inferiority complex that has taught us to scoff at anything that is local and slavishly extol cultures and commodities that are foreign needs to be uprooted from our culture and education. Unless we address our own slavish mentality, we will never learn to locate any goodness in us, let alone appreciate our literature which people take little interest in these days. Bangladeshi literature, in the past seventy-years, has produced some of the finest specimens of aesthetic works. Time has come to take proper notice of the generative capacity of Bangladeshi culture and life as we also take an honest look at its shortfalls.

The reason why I wish to go back to Khwabnama is because it makes me immensely proud of the Bangladeshi literary tradition each time I read this novel. As a student of world literature, one who has spent decades reading and discussing both canonical and non-canonical literature, I get to understand that this work marks the height of our creative potential. Only a handful of novels written in the past century can measure up to Elias' last work. It is a milestone in world literature and as the citizens of this land we should all take pride in its excellence, just as we should be proud of the working people of this country who have earned this hapless nation, sucked dry by the lumpen ruling elites, some degree of respectability on the world stage.

Akhtaruzzaman Elias, who is now considered an institution within the Bangladeshi literary tradition, was not as popular or well-known when he was alive. His life was cut short in January 1997, a month before his fifty-fourth birthday, by cancer that had been diagnosed just a year before. This novel, which was serialized in a national daily before being published as a book, was its author's last major work. Published first in 1996, Khwabnama still continues to both fascinate and baffle its readers. In an academic essay published in 2007, I argued that Elias' last novel falls within the perimeter of what Palestinian-American critic and activist Edward Said has described as "late style." Khwabnama's maze-like narrative, its thematic structure, and, of course, its immensely creative as well as inaccessible prose point towards its radical stylistic organization that Said calls late style. However, late work or not, Khowabnama remains Elias' most challenging work and, in every sense, his finest as well.

One distinctive feature of the novel comes into view right away: while most novels depend upon the development and struggles of individuals to tell their stories, Khwabnama relies on the shared experience of people to tell its own. At the heart of the novel's thematic structure stand the dreams, struggles and bafflements of the ordinary folks, mostly comprised of fishermen and landless farmers, who find their lives upended by Tebhaga Uprising on the one hand and the independence movement on the other. How the book of dream, Khwabnama, changes hands and, from the custody of dreamers and poets, eventually ends up in the possession of the opportunistic nouveau riche (the national bourgeoisie) is what the novel describes by using intricate yet extremely creative narrative strategy. An in-depth discussion about how the novel deploys metaphors, symbols and magic realist techniques to create a myth-ridden and mysterious world is not possible here, so let me quickly offer the justifications for calling Khwabnama a Bangladeshi epic.

The first thing that one needs to notice about Khwabnama is how it elevates rural Bangladeshi life to the epic stage, mythologizing the space and its way of life in the manner in which Garcia Marquez has mythologized Macondo/Columbia in One Hundred Years of Solitude. Yet, while Solitude's circular temporal arrangement is evocative of a pessimistic worldview, narrating the saga of a family destined for self-destruction and tragedy, Khwabnama, in a dialectical fashion, apprehends not only the tragic circularity of life but also its potential for transgression, its conditions of possibilities. Nevertheless, one can notice elegiac undertones in both novels because they both mourn the loss of historical possibilities ushered in by radical uprisings. It is here, in the way that these novels explore the depth of collective trauma and possibility, the somber tone with which they recount the losses of their nations and communities, that these novels elevate themselves to the level of epics, for an epic is, after all, a grand saga of collective human struggle that stretches beyond immediate history and communities.

The collective struggle that Khwabnama narrativizes resonates far beyond its fictional time and space. Although it tells the stories of Girirdanga and Nijgirirdanga, two communities located on the banks of Katlahar Bil [Katlahar Marsh], the themes that it engages with and the problems that it addresses remain pertinent to our era as well. The novel's critique of the national bourgeoisie is even more relevant today than it was in the mid-nineties, when it was first published. Likewise, the expropriation of the rural subaltern and the social/existential cost of ecological destruction are as compellingly present in our late neoliberal era as they were in the late 1940s, when urbanization and capitalization of rural communities were in their nascent stage. In many ways, this novel is a brilliant illustration of how the past mirrors onto the present and how the present continues to shape the way we look at our historical past. More importantly, this novel allows us to navigate the pre-history of our nation, showing how many of the themes and issues that emerged during the Tebhaga uprising and the partition riots still continue to mold our history today. One has to only look into the return of fascism and religious extremism in the mainframe of politics to understand how the unresolved past casts its shadows on life today. The grand canvas of Khwabnama accommodates the antinomies and polyphonies of life. That this novel does not suppress life's contradiction, that it declines to sanitize its narrative canvas by purging out unresolved mysteries and irrational desires, turns it into an enormously enriching tour de force. Khwabnama's epic stature, therefore, also emanates from its generous handling of reality, from its ability to pry open the external shell of reality to construct out of its carefully hidden soil and filth a narrative as broad as life itself.

Hasan Al Zayed teaches English and Cultural Studies at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments