Razia Khan: Life and Literature Archived

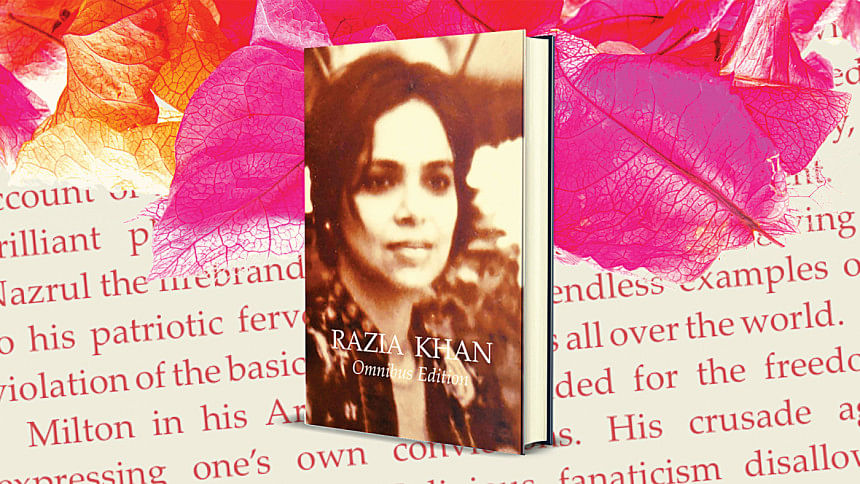

For anyone looking to immerse themself in the literary culture of Bangladesh, Professor Razia Khan Amin's name and presence are unavoidable. A poet, novelist, and literary critic (1936–2011) who taught some of the most prolific litterateurs of our time, her towering personality reaches the current generation through fascinating anecdotes. She was "a truly colourful person… precocious but also ahead of her time in her ideas and ways", Professor Fakrul Alam wrote in Once More into the Past (Daily Star Books, 2020), a collection of his essays earlier published in the Star Literature pages. "She led the young women going out to face the world. Led them into sunshine and self-confident awareness [...] with wit and anecdote, with original insight and analytic criticism", Professor Rebecca Haque wrote of her in another Daily Star tribute. "A brilliant woman and writer. I was among the few to never have been scolded by her", my own grandmother, author Farida Hossain, recalls fondly. These impressions from leading writers and academics bookend Razia Khan: Omnibus Edition, a collection of Razia Khan's writings published in December 2020 by her family, but it is the author's own voice and mind that shape the book as a valuable record of a moment in Bangladesh's history, as seen through the lenses of literature and free thought.

The book begins at a precarious moment in erstwhile East Pakistan. It is early 1970. Reverberations of India's Partition are still being felt, and doctors, lawyers, and small businessmen from India are beginning a life in East Pakistan amidst social and economic rejection, as the rest of the region hops confusedly between communal prejudice and awe for Western liberalism. "There is in the tense political and cultural atmosphere a pervading danger of narrowness of parochialism swallowing up whatever sanity and balance the East Pakistani has been able to achieve through these grinding years of trial and error", Dr Khan writes in the first essay of the collection, titled "The Exodus". This opening dispatch is short, sharp, and ominous, and what follows is a series of essays that call out the hypocrisies of the East Pakistani society in the making, using the same brevity and clarity of thought.

If her choice of topics pins each article down to a particular moment in time, the contexts she provides paint a vivid picture of time in motion. She writes of the poets of East Pakistan as descendants of a regional legacy and analyses the ways in which they engaged in dialogue with writers of the West and contemporary happenings of the East—such as when Syed Ali Ahsan and Sanaul Haq "gained fresh popularity through their translation of [...] Whitman and Pasternak", or how "[s]oon after Partition the intelligentsia in East Pakistan experienced an acute sense of spiritual disintegration which is reflected in a scattered way in the poetry of Ali Ahsan, Abu Jafar Shamsuddin, Ahsan Habib, Shamsur Rahman". Dr Khan relishes in these groupings and comparisons across her literary essays, both creating and revealing milieus among the poets she discusses, and the result is one in which much of East Pakistani literature ceases to feel like history and becomes accessible to someone looking to explore those terrains now.

One of these non-fiction pieces titled "Pangs of the Pedagogue", along with a speech delivered at a Venice PEN conference in 2006, will resonate with teachers, writers, and journalists today. Here, she writes about the MA and PhD degrees that an aspiring teacher would have to complete in order to make it as an educator, during which time they're unable to financially support a family, deprived of sufficient medical coverage and vacation days, while their contemporaries in business sectors earn up to five times as much. In her speech "Freedom of expression, human rights, writers", Dr Khan unapologetically states, "Coming to this conference from a third world country at my own expense and the innumerable rules that I had to obey have left a bad taste in my mouth." Save for the starting salaries she cites for teachers (Rs 350 a month!), it feels as though no time has passed since those early decades of the nation.

Introduced by writer Serajul Islam Chowdhury and academic-activist Hameeda Hossain, this selection of Dr Razia Khan's columns first appeared in Forum, the political weekly that came out between the 1960s and the start of the Liberation War in 1971. These are followed by her short stories, many of which appeared in The Daily Star's weekend magazine, and an unpublished novella that was serendipitously found in a laptop, ready to be sent off to a publisher. Tributes by writers including Kaiser Haq, Rebecca Haque, Azfar Hussain, and several others bring up the rear, followed by photographs from Razia Khan's literary and academic life—in Karachi, in Bangla Academy, in Baker Street London, and at Dhaka University's Rokeya Hall, of which she was provost.

When met with a book that compiles previously published writings by an author, my first question is always, "Why"? Why should I buy this book when its contents might be readily available to me, for free, on the internet? The answer usually lies in the editorial hand whose invisible touch adds something greater than the sum of the parts to a book. In this case, save for a few typing errors, this quality can be found in the flow of ideas permeating the collection. It first introduces a prolific writer's commentary on the socio-political climate of a nation in transition and the arts and culture brewing in that time and space. Then, it showcases how she wove those ingredients into her own rendition of that world, accentuated by characteristics that we lovers of literature especially enjoy—the romances and ideas that bloom in the close-knit English departments of university campuses.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor, Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments