Women’s working hours and valuation of their unpaid care work

Women's empowerment requires that women contribute to the society and the economy and it is also important for these contributions to be adequately recognised.

Generation of necessary data and development of appropriate conceptual framework for gender disaggregated analysis are prerequisites for this.

The important steps forward in this respect have been the research on inclusion of the value of women's unpaid family service in the national GDP estimates.

During the last few decades there have been extensive research on estimation of the value of women's domestic activities and care activities for family.

It has been estimated that its addition to GDP is likely to raise the total GDP value in the ranges of 20 to 80 per cent in some of the developing countries of Asia.

It is not surprising that the official GDP estimation method remains unchanged. There are a number of reasons behind the absence of any significant initiative to change it in response to the recent thinking on inclusion of women's unpaid work in GDP.

The mainstream economists may not be interested in such change because this would imply that all analysis of GDP growth and the impact of traditional policies on such growth, or in other words the entire economic analysis would have to change.

Such change is unthinkable in the present state of the discipline.

One may also notice that the difference in men's and women's contribution to domestic work is much higher in developing countries compared to high-income countries.

In the high-income countries, many of these services are purchased in the market and the use of machinery and other amenities has reduced the time required for such activities.

In the given circumstances, recognition of women's contribution to the economy requires attention to other aspects which may throw light on women's hard work while combining activities of 'employment' and 'household services for own family use'.

Of course, this is not being suggested as an alternative to the research on women's contribution to GDP but is expected to complement that.

Women's working hours received attention as soon as women's participation in labour force and in paid employment soared in the high-income countries.

It was soon realised that it imposes a "double day" on women.

In Bangladesh, the extent of participation of women in paid work is rising but is still lower than the high or higher middle-income countries.

Growth of employment in RMG sector, in addition to other forces, led to rise in the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) for women. Long working hours received attention in the context of RMG workers, but it must extend beyond that.

There has been hardly any analysis based on national data on this and how the responsibility of domestic work aggravates the situation.

Studies have observed that alongside underemployment, long working hours is also a reality for both men and women in the labour market of Bangladesh. However, there is hardly any acknowledgement that a large percentage of employed women also work excessive hours.

Therefore, it is essential to take a closer look at the data on working hours of women.

In addition, one must also recognise the role of care work performed by women not only in terms of its value addition and raising the size of GDP but also in terms of total workload of women.

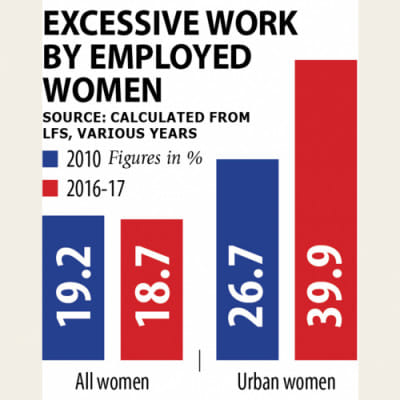

If needed, women can work not only fulltime but also excess hours. If 50 hours per week is regarded as a cut-off point for excessive work, a large share of working women are subject to excessive hours, even if one considers only the hours in income earning work.

The situation is worse for women in urban areas.

In 2016-17, about 40 per cent of employed women in urban areas worked excessive hours. The proportion of urban women working excessive hours increased during 2010 to 2016-17.

On the whole, working hour is not so much a choice left to the worker but it depends on the demand side. One has to accept the working hours as a given factor when accepting a specific type of activity/occupation and such acceptance is a strategy for survival among poorer women in Bangladesh.

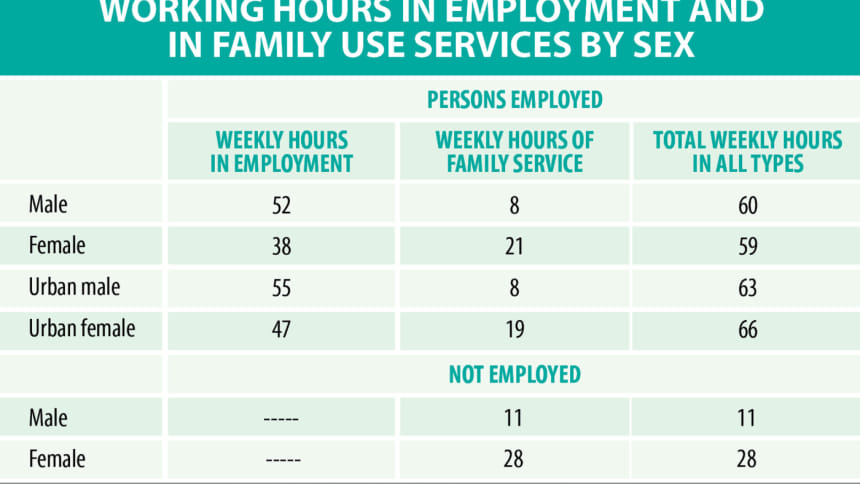

The above data focuses only on hours spent on income earning activities. On top of that both men and women are likely to work in the production of services for household. When the two are added, in the urban areas, the average hours worked by women is higher compared to men. These are respectively 66 and 53 hours per week.

For those not employed and are engaged only in the production of home services, men work much smaller number of hours than women. This glaring difference must be highlighted. Even the total working hour does not fully capture the low-paid working women's burden and drudgery.

To this total hour, one must add the time for commuting to the place of work as most of them walk to their workplaces due to a lack of availability of women-friendly public transport services.

These findings imply that appropriate conceptual framework for generation of data on female labour market and its analysis can help policy advocacy for gender equality in the relevant sphere and recognition of women's contribution to the economy, family and society at large.

As a concluding remark, it should be emphasised that this indicator is easy to visualise and one may easily relate it to everyday experience in the society and family.

This indicator may better appeal to the conscience of the policymakers to adopt policies for provision of services for working women which could reduce drudgery and the length of working hours in the domestic front.

The write is executive chairperson of the Centre for Development and Employment Research (CDER).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments