Apparel exports: resilience and future challenges

The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in over 114 million infections and a staggering 2.5 million deaths worldwide. It has crippled health systems, deteriorated living standards, and exacerbated inequality.

One area in which the pandemic was expected to have a devastating impact was on international trade. But after a sharp drop in the first half of 2020, global merchandise trade appears to be on track for a steady recovery. The UNCTAD recently revised their forecasted decline in global merchandise exports from 9 per cent to 5.6 per cent for 2020.

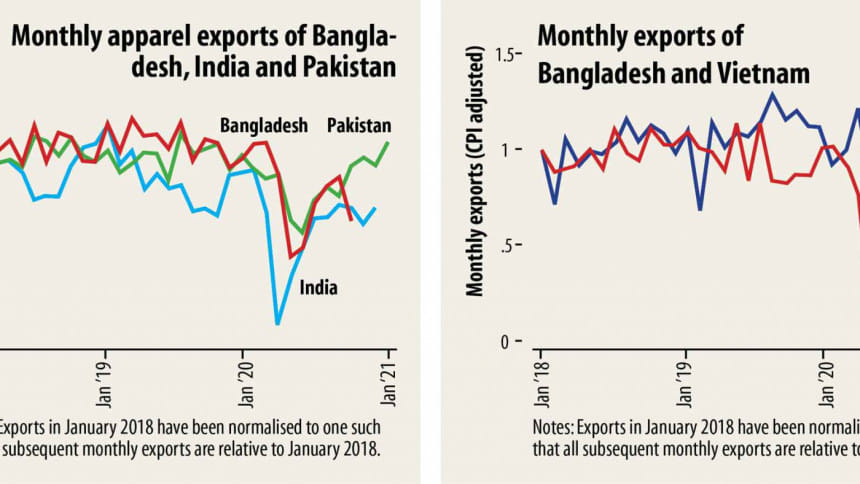

A similar pattern is also playing out in Bangladesh, where according to our estimates, total exports were down 33 per cent year-on-year in the first half of 2020 but showed signs of a steady recovery towards the end of the year. We also observe similar patterns in the South Asian countries.

In the case of the apparel industry, this recovery has been driven by three factors. After an initial decline in demand from Western markets early last year, apparel purchases partly recovered in the summer. This allowed Bangladeshi producers to increase export shipments and recoup some of their lost profits.

Second, the brief lockdown in Bangladesh itself helped prevent significant work stoppages. Even during the lockdown, the BGMEA announced a reopening of factories from April 26 in 2020 to complete existing orders.

While the less stringent lockdown carried a public health risk, its impact on disease spread has been relatively minimal.

Our recent work points to a third explanation: the lack of supply chain disruptions. This was due to two main factors: a swift recovery in Chinese exports—the main source of Bangladesh's imported inputs—as well as import diversion away from Covid-impacted source countries.

The nimble management of supply chains ensured that exporters were in a good position to deliver when orders recovered.

Concerns about these disruptions had caused many analysts to argue that the current global supply chains expose firms to excessive risk and are no longer "fit for purpose".

There were sober predictions that supply chains in the post-Covid world would be shorter and less geographically dispersed.

The resilience we document suggests that global supply chains are not as fragile as initially feared and thus a major restructuring is perhaps not likely. This will be a relief to many countries like Bangladesh for whom links to these supply chains have helped in promoting economic development.

Nonetheless, Covid-19 has highlighted several trade policy challenges for Bangladesh. First, it has again emphasised the dangers of its export concentration in apparel, an industry that has suffered some of the sharpest drops in consumer spending during the pandemic.

According to the US Census's Monthly Retail Trade Survey, clothing and clothing accessory stores experienced a 51 per cent reduction in sales in March 2020.

This is not surprising given that lockdowns have resulted in people increasingly working from home with little need to splurge on new clothing.

The dependence on apparel also partly explains the much sharper decline in Bangladesh's overall exports compared to that of Vietnam, which is a large apparel exporter but has a much more diversified export basket.

By one measure, Bangladesh's exports are five times as concentrated as that of Vietnam.

Thus, given how sensitive apparel demand appears to be to economic downturns, lowering Bangladesh's export concentration in that industry will be an important way to diversify its risks and crisis-proof the country's exports in the future.

The second policy challenge is the significant headwinds that are likely in store for Bangladesh's exports.

After the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, the world experienced a prolonged period of "slowbalisation", where trade growth slowed dramatically. Such a scenario is likely over the next few years.

Indeed, after a difficult winter in Europe and North America, growth in apparel orders for the spring have been disappointing and suggests that the rate of recovery seen at the end of 2020 will likely slow down.

The past year has been an incredibly challenging one for Bangladesh's exports. Cancelled orders and reduced employment had left both firms and workers in a precarious position. While the near-term prospects appear better than one would have expected at this time last year, there are nonetheless significant challenges ahead.

But the resilience shown in 2020—both among producers and workers—provides a hopeful outlook for the future.

Reshad N Ahsan is an associate professor of the department of economics of the University of Melbourne and Kazi Iqbal is the senior research fellow of Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments