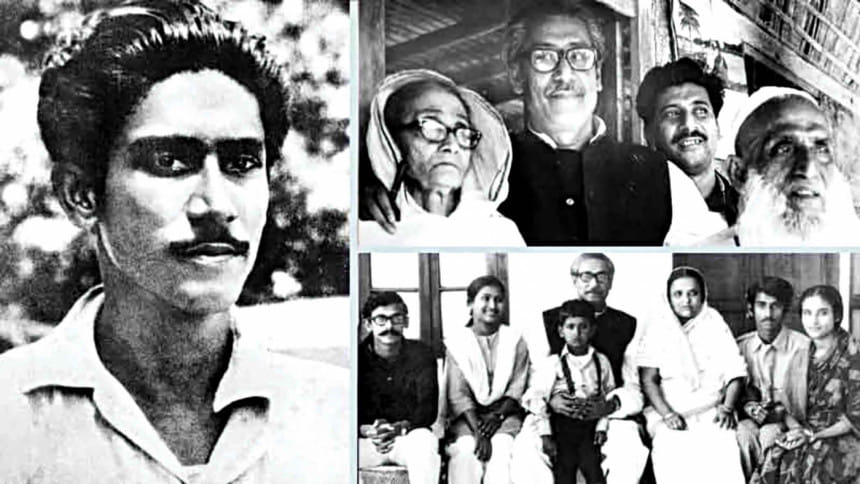

A tribute to the nation’s architect

March 17 shall forever remain a memorable day in the annuls of Bangladesh's political history, as well as in the hearts of millions of Bengalis as, on this day, the supreme leader and the progenitor of sovereign Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (fondly called Bangabandhu by his people), was born. His entire life was an exercise in liberating Bengalis from the shackles of political bondage and economic deprivation, and one can gauge the enormity of his sacrifice in terms of personal freedom when one sees that the better part of his youth was spent in incarceration for upholding the people's cause. The depth of his public-spiritedness was simply stupendous.

The post-liberation generations of Bangladesh need to know and appreciate that our notions of separateness in Pakistan required major political efforts to be transformed into a sense of shared nationhood. As Nitish K. Sengupta aptly put it in Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib, "that catalytic act of political entrepreneurship needed to forge a sense of nationhood for the Bangalis was provided by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. From the period in 1966 when Bangabandhu launched the Six Point Programme down to the defining two year period from March 1969 to March 1971, in the course of an election campaign of unique historical significance, Bangabandhu played a dominant role in the struggle for self-rule for the Bangalis."

The defiant architect of Bangladesh was characteristically forthright when on March 1, 1971, Yahya Khan unilaterally announced the postponement sine die of the National Assembly. He said that the postponement was made "only for the sake of a minority party's disagreement" and that they were "representatives of the majority people" and could not allow it to go "unchallenged". The following day, Bangabandhu announced a programme for the next six days—including a complete strike in Dhaka—a province-wide strike on March 3, when the assembly was to have met, and a public meeting at the Race Course on March 7. The speech on March 7 opened a new chapter in our glorious political progression, and the rest is history.

Bangabandhu's uniqueness could be understood from the fact that he was the first major political leader who, through his historic enunciation of Six Point Programme in 1966, reflected a formal recognition of the impossibility of political co-existence between East and West Pakistan. Quite clearly, he played a critical role in institutionalising the growing sense of separateness between East and West Pakistan through his now-famous Six Point Programme, and made sure that the election of 1970 gave a thumping nod to his call. The election results helped in forging a sense of national identity for the Bengali.

It was clearly Bangabandhu who had articulated our national identity by sharply defining the "emergence of two economies, two politics and two societies within a unified Pakistan where the socio-political formations which came to rule Bangladesh remained quite distinct from those who retained power in West Pakistan".

Let us remember that the unchallenged authority of Bangabandhu was instrumental to the sustainability of the Liberation War. He commanded the freely-given and overwhelming electoral mandate to speak for Bangladesh and exercised de facto authority in the eyes of the world over the territory of Bangladesh when he proclaimed Bangladesh's independence. "It was only in Bangladesh that…. servants of colonial rule repudiated the authority of the ruler and supported a 'rebel' authority because they deemed its leader a legitimate authority to speak for all the people of Bangladesh."

Dispassionate Bangladeshis can gauge the intrepidity of Bangabandhu by understanding the socio-economic realities of post-partition East Pakistan. At a time when there was a real dearth of educated and conscious Bengali activists, Bangabandhu was Bengal's fearless spokesperson, continuously defying the establishment. Here was a leader who spent two-thirds of his youth in jail for advocating for Bengal's causes. History testifies that he never compromised with his political commitment, and the decade of 1960 to 1970 witnessed proud and forthright Bengalis protesting and dominating Pakistan's political landscape. Bangabandhu's deft political stewardship galvanised the entire Bengali population.

One has to imagine the initial years of the decade starting in 1960, when the Pakistani military junta took upon itself the task of teaching the nation about the basics of democracy and found spineless collaborators from this part of the world; one has to think of that time when East Pakistan's political world was pathetically lackadaisical and courage was in short supply. It was in such circumstances that the Bengalis had to be awakened from their somnolence, if not deep slumber.

One also has to imagine the 1960s, when Bengalis of erstwhile East Pakistan were subjected to the most humiliating treatment. It is no exaggeration to say that they were experiencing the tribulations of a colonised people. In an atmosphere of all-pervasive fear and subjugation, it was Bangabandhu who confronted the mighty Field Marshal Ayub Khan and showed the guts to forcefully advocate the rights of fellow Bengalis. During the trial of the so-called Agartala Conspiracy Case in Dhaka's Cantonment, Bangabandhu took to task the rogue Pakistani army personnel and cautioned them to behave. He did not agree to participate in the Round Table Conference as a prisoner. The 1960s were, in fact, a time when all Bengalis could justifiably take pride in their gutsy manners that drew sustenance from Bangabandhu's defiant disposition.

Bangladeshis need to know that Bangabandhu was a real epitome of courage, both physically and morally. The historic Six Point Programme, an explicit embodiment of Bengali nationalism, was unfurled at Lahore (the heart of Punjab) by Bangabandhu. In Lahore, the bastion of arrogant Punjabi power, Bangabandhu displayed admirable physical and moral courage during the course of a public meeting that he addressed in 1970.

It so happened that his speech was being purposely interrupted by some Muslim League-Jamaat hirelings. When these elements did not stop despite being cautioned to, Bangabandhu shouted out, threatening that he had not come to Lahore seeking votes as he had plenty of them in East Pakistan, and that they should either listen to him or disappear from the meeting area. No Bengali had ever publicly ventured to rebuke the power-obsessed Punjabis in such a raw manner.

Bangabandhu was gifted with extraordinary organisational acumen and had an inkling of the mischief of the Pakistani military junta. Accordingly, he exhorted the people for an imminent armed struggle. His historic March 7 speech bears eloquent testimony to that. Precariously positioned as he was in the extremely demanding and tumultuous days of March 1971, Bangabandhu acted as a constitutional politician with supreme forbearance.

We must appreciate that Bangabandhu could never be cowered into submission. The trappings of power did not allure him and he remained a solid rock in the shifting sands. It is time once again for grateful Bangladeshis to remember and pay homage to the great architect of our nation.

Muhammad Nurul Huda is a former IGP of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments