NRB expertise and skills must be tapped aggressively

Non-resident Bangladeshis (NRB) have played an important role in the economic growth of the motherland. Whether it is the remittances we are talking about or the "diaspora network" that facilitates technology transfer, NRBs have increasingly energised our economy as well. Nonetheless, compared with what other countries such as China, India and the Philippines have reaped in terms of the globalisation dividend, Bangladesh still has a long way to go. The NRBs on the one hand, and the public and private sector on the other, have a lot of work to do if we want to pull our country out of the "transition to middle-income" status and propel it into a robust and autonomous growth path.

Let me first take up an issue that I mentioned above, i.e., the contribution of the NRBs to our foreign exchange coffers. Defying all expectations, Bangladeshis working abroad have increased the volume of money they send home during the Covid-19 crisis. Even as late as June 2020, in the thick of the Covid-19 pandemic, the World Economic Forum forewarned of a looming remittance crisis; but Bangladeshis working abroad bucked the trend. While the amount of money migrant workers send home globally is projected to decrease by 14 percent by 2021, according to the World Bank, Bangladesh reportedly witnessed a "whopping" 53.5 percent year on year increase in remittance flows during the July-September period in 2020. Buoyed by these news, the government has outlined a plan to raise USD 150 billion through remittances in the next five years.

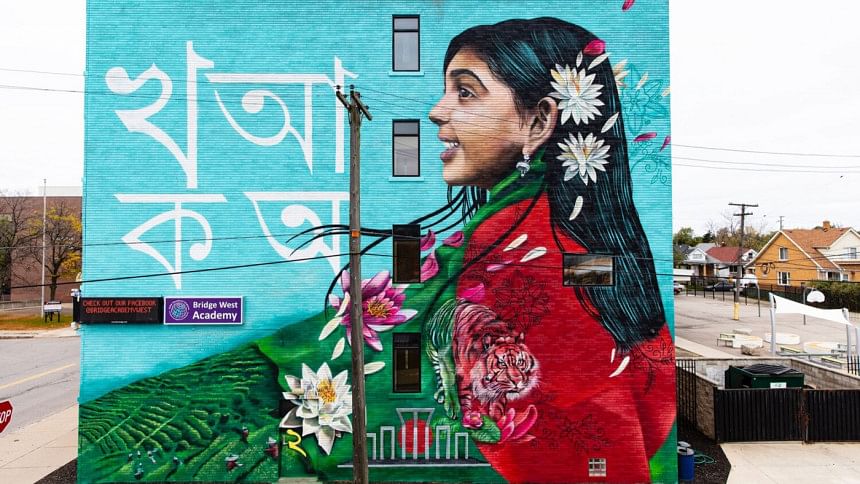

Who are these Bangladeshis? According to the information of Bangladesh's Wage Earners' Welfare Board, around 1.2 crore Bangladeshi workers reside abroad, and they are spread out all over the globe. The National Board of Revenue (NBR) categorises a Non-resident Bangladeshi (NRB) as a Bangladeshi citizen living abroad with valid status. This could either be as a foreign country's permanent resident or with a valid work permit. However, this definition still leaves out those who are living abroad without a "valid status" and make contributions to our economic well-being. While Saudi Arabia and UAE were the first and second "countries of origin" in terms of remittances for Bangladesh, over the last seven months, the US has taken the second spot, overtaking the UAE. And needless to mention that many of the Bangladeshis living in the US do not have any legal status. The flow of remittances has helped us to reduce poverty, overcome food insecurity, support balance of payments, and boost our economic growth.

The question is, how else do the NRBs contribute to the development of Bangladesh besides providing remittance? We can identify three additional areas: investment, networking, and knowledge transfer. Migrants engage in direct and portfolio investments, or through the establishment of new ventures in their homelands. Much has been written in professional journals and the media about the impact of the "diaspora" on their home countries. Many countries, both developed and developing, have successfully tapped into their respective diaspora to enhance the growth and development in their respective home economies.

Looking into the future, we can see the wisdom of the statement made by Yevgeny Kuznetsov more than a decade ago. "Expatriates do not need to be investors or make financial contributions to have an impact on their home countries. They can serve as "bridges" by providing access to markets, sources of investment, and expertise. Influential members of diasporas can shape public debate, articulate reform plans, and help implement reforms and new projects. Policy expertise and managerial and marketing knowledge are the most significant resources of diaspora networks."

Increasingly, even the entry-level jobs they take in factory production or the healthcare sector in host countries demand and teach problem-solving skills that blur the line between management and labour. Whether these new skills can be redeployed back home is an open question, but the changing nature of migrants' work suggests the possibility that these "birds of passage", traditionally in transit between a native land that cannot support them and a rich country that remains alien, may one day form distinctive, medium-skill diaspora networks that complement the diasporas of managers and entrepreneurs.

Bangladeshi diaspora comes in different shapes and sizes, and a government agency dedicated to NRB affairs would be well-advised to consider these angles in proposing future policy actions. A "one size fits all" policy or programme will not be able to take full advantage of the remittance pool or talent, and a sizeable magnitude will remain untapped. For example, during my recent discussion, Rezaul Haque, a senior manager at Intel Corporation mentioned that many of his fellow NRBs, as well as tech giants, are keenly interested in partnership with government entities.

Secondly, an NRB's decision to save and remit is to a considerable degree driven by a rational process where he/she weighs the choices he/she faces with his/her earnings, and the opportunities for investment in both the host country and Bangladesh. While NRBs receive some savings/investment benefits offered by Bangladesh Bank, including Non-Resident Foreign Currency Deposit, Wage Earners' Development Bond, Non-Resident Investor's Taka Account, etc, there is a need for these to be streamlined.

Kathleen Newland and Sonia Plaza of Migration Policy Institute recommend that "governments can certainly do more to remove obstacles and create opportunities for diasporas to engage in economic development. Specific actions include identifying goals, mapping diaspora location and skills, fostering a relationship of trust with the diaspora, maintaining sophisticated means of communication with the diaspora, and ultimately encouraging diaspora contributions to national development." Migrants and diasporas are, to some extent, "unexploited capital".

Our government and the various ministries and departments, including the Expatriates' Welfare and Overseas Employment and Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET) need to review their programmes to draw in the expertise of NRBs.

I will not dwell on the strengths that migrant entrepreneurs and technologists bring to the table. Migrants can reduce the transaction costs by assisting businesses in navigating informal trade barriers and overcoming the communication and language barriers typical of two natives from two different countries. Migrants are also more likely to know the regulatory environment in both countries, which are crucial for establishing bilateral business transactions. With the help of the Chinese diaspora, China has won the race to become the world's factory. In a similar vein, with the help of the Indian diaspora, India could become the world's technology lab. Capital from diaspora investment and entrepreneurship has also played an important role in industrialised countries, such as Israel, Ireland, and Italy, furthering economic growth and innovation.

What is also missing, however, is a way to inform the NRBs and a way for them to stay connected to the research, educational, and governmental systems in Bangladesh. Given the reservations that the expatriate communities have about the existing economic system (since its very inefficiencies were prime reasons for emigrating), the formulation of any network method to enable the transfer of knowledge should be a first step.

One idea that has been implemented in other countries is the creation of a professional network on the internet. The creation of an electronic database along the lines of LinkedIn for Bangladeshis can be a platform for NRBs from various backgrounds, such as STEM experts, SME owners, and skilled professionals. The goal of the network would be to provide a registry of highly skilled Bangladeshis who live and work abroad; a global map and network of NRB scientists, professionals, and entrepreneurs; and updated information on opportunities in Bangladesh.

The most important factor that we need to keep in mind is that NRBs have a lack of information about how they can help Bangladesh and how to connect with other Bangladeshis with similar professional interests. Whether or not an expatriate intends to physically return soon, there is an immediate need for a virtual return of knowledge and experience as well as interconnectivity with Bangladesh. The defining characteristic of networks of expatriate professionals, also known as "diaspora networks", is that they pertain to talent—be it technical, managerial, or creative.

Dr Abdullah Shibli is an economist and has been working in higher education and information technology for 35 years in the USA and Bangladesh. He is also Senior Research Fellow, International Sustainable Development Institute (ISDI), a think-tank in Boston, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments