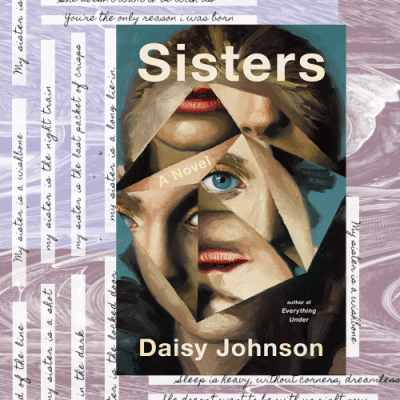

Gothic fiction writ anew in Daisy Johnson’s ‘Sisters’

One of 2020's more positive highlights was Daisy Johnson's stunning sophomore effort, Sisters (Riverhead Books). The novel, a Gothic-domestic drama, starts with siblings September and July in the backseat of a car, on their way to the "Settle House". We find descriptions and the scene set early for us: "We have never lived in a house with a name before. Never lived in a house that looks the way this one does: rankled, bentouttashape, dirtyallover". The house is presumably somewhere desolate, enclosed by a sea, or a waterbody, and a beach, and by the time they arrive their mother's body "looks as if it is too much to carry. She has been this way", we learn, "taciturn or silent, ever since what happened at school". What that something is drags behind the character's feet, and grows no lighter through the pages.

The younger of the sisters, July, narrates the majority of this story, but is far from its driving source. That responsibility is seized firmly in the palms and whims of September, who was born in this very house, she says to July, one of many lies that may or may not be true. The reasons for the three to be marooned in the Settle House are more and more kept at bay, and just as well forgotten as the plot we are shown tiptoes around the plot that actually is. There is so much kept just at the cusp. The terror is one of presumed terror.

There are no spirits or ghouls in sight, presumably, but the Settle House is the most haunted, horrid thing. The way the wood of its floorboards creaks, the way everything—the normalest things—plays out in the rottenest air, the way the past unfolds, is told to us, and we are waiting, simply waiting, for something horrible to have happened. And for every bad that happens, we always expect something worse.

The novel brings to mind The Turn of the Screw (1898). In the 1961 film The Innocents, possibly the best iteration of Henry James' spectral tale, the central groove of the picture's many terrors is the thought it leaves the audience: "Is it the children that are haunted, or is it the Bly House?" The mother of Sisters resembles, and often is, the picture of James' Governess, and the children at their worst could easily double for Flora and Miles. We know there's something going on, something wrong, and the novel dangles its own set of questions before the reader's eyes, but it sustains the mysteries right to the last letter.

One of the book's greatest terrors, of course, is the titular relationship. A symbiotic growth of a sisterhood, July and September live off one another to the point that feelings, sensations, thoughts, and prose are shared. "Is Mum crying? I don't know. Should we ask?" reads a line, rattling in the middle of July's narrations. Though the interruptions lessen as the novel goes, the interdependency does not.

July is disconcertingly subservient to the older September, and gladly plays "September Says", a thought-up game that teeters between misbehaviour and malevolence. But September is there, too; the first to ask how July is doing, the first to gather a meal or snacks, the first to braid her hair for the day. Johnson's greatest success in writing this novel is leaving in all the "good parts" that always exist in such an abusive relationship.

A good deal happens from chapter to chapter in this book, and the thrill of the unwrapping is paramount to the Gothic story. This review has left several details out, and should perhaps leave out more. The best means of enjoying this novel is to read, and to unwrap, and gasp and squirm and draw near when applicable.

Mehrul Bari S Chowdhury is a writer, poet, and artist. His work has appeared in Sortes Magazine, Kitaab, Six Seasons Review, among others.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments