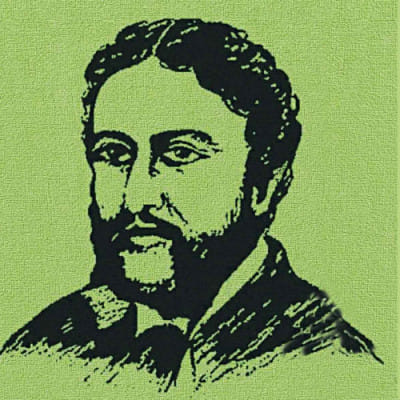

The prodigal son of Bangla literature: Michael Madhusudan Datta

While the great playwrights of various cultures wrote drama, Bengal Michael Madhusudan Datta truly lived it in his single-minded, flawed, but ultimately successful odyssey to greatness.

Known as "Modhu Kobi," this literary giant of Bengal was born in Sagardari, Jessore, where even now, the poet's birthday is marked by the Modhu Mela every year. Michael was a precocious and brilliant child, born into and imbibed the grandeur of a wealthy, traditional, and grand zamindari, and perhaps that is what influenced his dreams of greatness of a different kind.

My introduction to Madhusudan was in class six, when I was to memorise the poem "Roshal o Shornolotika" as part of the Bangla curriculum. It was a long poem, with a lot of unfamiliar words, and daunting, to say the least. Yet, this poem in some ways opened my eyes to the beauty of "old school language," which we also called "shadhu bhasha," which to children appears quite staid and arcane. Yet, the way the poem flowed as my father recited and helped me understand the words, etched in my memory, the words still alive in my mind, the moral of humility, forever learnt—

"Haraiya Ayu-shoho Dorpo Bonosthol-e!

Urdho-sheer Jodi Tumi Kul Maan Dhon-e;

Koriyo Na Ghrina Tobu Nich-sheer Jon-e!"

Michael was multitalented, writing prose, poetry, plays et all with equal flair, and is credited for introducing satire as well as the sonnet to Bengali poetry. He was also the first to use the blank verse in Bangla poetry. Not only that, along with Bengali, English, French and Italian, in which he was well-versed, he was conversationally fluent in about a dozen languages, including Hebrew, Telugu and Sanskrit.

Michael possessed a singularly talented and obstinate mind from his very childhood, which eventually pushed him to leave behind his beloved father, religion, and country, in pursuit of greatness as a poet. Fascinated by the cultural renaissance happening around him, and much like youth anywhere, Michael was enamoured by the courtly and formal conduct of the British. He chose to pursue English poetry as his passion, and dreamt of becoming a famous English poet, idolising Lord Byron.

While his early work was published in the English language publication in British India, he aspired to a global acceptance of his talent, and sent off his work to publications in England, to be snubbed. Whether it was for the quality of the work in the editors' judgement, or the prejudice against a brown man writing in English, can never be ascertained for sure, but Michael took it to heart that to get that coveted recognition, he must go abroad and make that name for himself there. He felt that English language and literary traditions were far richer than Bangla, and that his talent would be properly valued and recognised only if he pursued literature in English. For a long while, he remained bewitched by that concept.

In brashness typical of a proud and ambitious young man, he also felt he knew what was best for himself in terms of matters of marriage. The common custom for an upper caste and wealthy Hindu bachelor was to marry whichever suitably upper caste and wealthy girl the parents chose. But Michael believed that it would be horrific to fall into that trope and to marry without love or a proper courtship, a true tragedy.

Thus, with an aim to avoid an arranged marriage, and to make it easier for himself to go abroad and pursue greatness supported by a westernised name, Madhusudan converted to Christianity and added Michael to his name at just nineteen. This decision earned his erstwhile indulgent father's permanent ire, lost him his place at the Hindu College, and lead him to a path of hardship and greatness at the same time. It ultimately also lost him the support and wealth of his father, who paid for his education, but seeing that Michael would not revert to Hinduism, finally disowned him, despite his being an only child.

Being removed from Hindu college on account of his conversion, he now continued his education at Bishop's College, firmly set in his love for English literature, and his pursuit of fame.

From his birth to 1856, his focus remained on English literary practices, and after an initial struggle, he turned around his fortunes while working as an editor of various publications in Madras, where he also met and married both his non-Indian wives.

Only upon the death of his estranged father, Madhusudan returned to Kolkata, and upon the urging of his friends and members of the literary circles, felt the need to explore his potential in Bangla well. And unexpectedly, this is what brought him the greatness he had sought for so long. He ultimately made it to the land of dreams, on the pretext of studying law, had his heart broken by financial struggles and racism, and came back to India. That is another long story.

But this brilliant and permanently rebellious man did achieve greatness he so desired. Once his interest in Bangla was piqued, he broke rules and crated things anew in everything he put his hands on. From poems to epics, from satire to plays, everything he wrote, even his letters, were ground-breaking and introduced hitherto foreign aspects to Bangla literature. He was truly a great moderniser, ushering Bangla literary practices into the modern age.

The epic Meghnad Bodh is perhaps his most celebrated work, called a "Mohakabba," might be what he most known for, but he also wrote the truly first authentic and original play in Bangla literature, called Sharmishta. Michael was among the first to show themes of latent feminism in Bangla writers, his heroines always self-aware, unabashed in their womanhood, and vocal about their rights, like his versions of Jona and Koikeyi, the well-known characters of Ramayana, which he used as the source material for his epic poem Meghnad Bodh.

Madhusudan also used metaphors with abandon, and was not afraid to voice his opinions, case in point his satires— "Ekei ki boley shobbhota" and "Buro Shalik er Ghar e roun." The first was a critique of the alcohol and drug abuse by the young and educated young Bengalis, ironic in the sense that that was once his very own lifestyle, and the second criticised the heavily hypocritical and ritualised ways of the traditional Hindu society, which he found largely devoid of morality.

In his poem Bongobhumir proti, written at the later stage of his life, there is a clear indication of regret, of ignoring his motherland, and for thinking of her charms as inferior. There is pleading for forgiveness;

"Rekho Ma Dashey-re Mon-e

Shadhite Mon-er Shaadh

Ghot-ey jodi Promad

Modhuheen Koro Na Go Tobo Monokokonod-e…"

Another poem he begins,

"Nij Agar-e Chilo More Omullo Roton Ogonno

Ta Shob-ey Ami Obohela Kori,

Ortho-lobhey Korinu Deshey Deshey Bhromon,

Bodorey Bondorey Jotha Banijjo Tori…"

To end with:

Nij Grihey Dhon Tobo, Tobey Ki Karoney,

Bhikhari Tumi Hey Aji, Koho Dhon Poti?

Keno Niranondo Tumi Anondo Shodoney?

Michael was Bengali literature's flamboyant prodigal son, the one who returned. He died tragically young, at just 49, and in severe financial hardship due to his eccentric and irresponsible nature, and betrayal by relatives. Forever swimming against the flow, a pioneer, a man after his own heart, Michael Madhusudan Datta stands tall as a legend in Bangla literature, a harbinger of the new and the novel — his stature cemented in time and infallible to challenge.

Photo: Collected

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments