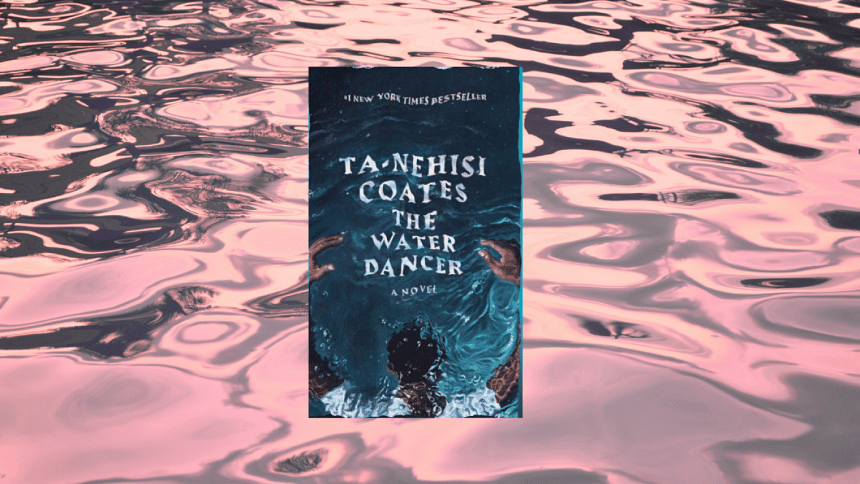

To drown is to be free in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s ‘The Water Dancer’

The Water Dancer (Random House, 2020) follows the life of one Hiram Walker, whose biological mother is a slave and father a slaver. Born as a slave bound to the shackles of a plantation in Virginia, Hiram is unique from the others who work beside him. He has a sharp and photogenic memory. And as he grows up with a pang of grief left by the absence of his mother, he discovers another life-changing superpower: Conduction, a form of teleporting through time and space and inspired by Harriet Tubman's phenomenal work of secretly ferrying slaves to freedom. His extraordinary powers bring him under the mercy of some privilege—like private tutoring alongside his white half-brother—that other slaves cannot enjoy.

His "makeshift family" on the plantation consists of Thena, his adoptive mother, and Sophia, his romantic interest. He is soon snatched by deception into the clutch of "low-whites"(those used by the elite white people to nab runaway and even freed slaves) from the world he has known all his life. As the story progresses with the decline of the white owners' wealth and resources, we follow Hiram into the world of the Underground. He becomes one of the secret agents who dedicate their lives to liberate the enslaved.

Through these agents and the ways in which they wage a war on slavery, we get a vivid glimpse into the horrors of slavery. "…[T]hese coloureds of Starfall existed in the shadow of an awesome power, which, at a whim, could clap them back into chains." We also see the trials and tribulations Hiram faces in mastering his wavering power of Conduction and in coming to terms with varying degrees of loss.

As someone who admires films such as Twelve Years A Slave and Harriet, and books such as Beloved by Toni Morrison, Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, and Washington Black by Esi Edugyan, I had high expectations from this novel. After all, it had a supernatural angle to the often-told narrative of slavery.

However, I felt as if an invisible wall blocked me from connecting with the landscape. Aside from Hiram, Thena, and Sophie, the other characters—especially the secret agents of the Underground—were poorly fleshed out. I would have preferred them having more stage time. As such, the tragedies striking their lives and the trajectory spinning them through time seemed weak and dull. What Coates expected to deliver through their stories failed to stir me. I believe that this issue would not have existed if the characters heavily populating the second half of the novel were built more carefully and if the novel employed a slower pace.

What makes the aforementioned novels work is that they hook the reader in firmly. The Water Dancer, even though ambitious, left me craving more action and high-geared moments of grief, suspense, climax, and character development.

I did, however, enjoy the lyrical prose and all that it says about the tragic truths about slavery, and the metaphor Coates uses for slaves passing the ruthless transatlantic slave route—drowning in the Atlantic is shown as a form of liberation from the shadows of slavery in the novel.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments