Will Mars ever be habitable?

At least, that's the plan, but as we all might have guessed, landing humans on Mars isn't the only difficult part of the mission. Living there is a greater challenge. Mars is not Earth, it has its own identity—the arid world doesn't compare to the bearer of about 75 percent water on its surface. So, the real mission is making Mars habitable for humans.

The first colonisers will be given the task of turning Mars into an environment which can sustain life. Simply put, they need to "terraform" Mars, which means the Martian atmospheric conditions need to be manipulated to make them more like that of Earth, so that humans can live, breathe and reproduce freely.

Surely, that is not going to be an easy undertaking. However, Robert Zubrin, in his celebrated book The Case for Mars, is able to a put the subject in an optimistic light. His argument is that if Earth could be made into a self-sustainable planet, the same can be done to Mars.

In its infancy, Earth did not have any oxygen and was barren, much like Mars is now. Only due to the presence of photosynthetic organisms, which used carbon dioxide up and gave out oxygen, the composition of Earth's atmosphere had evolved, leading to the evolution of human beings. So, if the atmosphere of Mars can be manipulated to make it denser and warmer, theoretically it could also support life.

We understand what needs to be done, but how exactly can we go about making Mars hospitable to humans? The answer may lie in the reservoir of carbon dioxide present in the ice caps or under the soil surface on Mars. Carbon dioxide, among other things, is infamous for being a greenhouse gas and contributing to global warming on Earth. We may not want Earth to heat up as a result of global warming more than it has already, but frankly, Mars could use some greenhouse gases. Zubrin points out that the release of carbon dioxide, methane and the production of chlorofluorocarbons or CFCs could lead to a thicker Martian atmosphere, which will be able to trap heat and make Mars warmer.

To accomplish such a feat, Zubrin proposes some innovative solutions. The first, is using orbiting mirrors to direct heat towards specific areas in Mars' south pole. A temperature rise of five degrees (in Kelvins) would be able to cause the dry ice to evaporate, releasing carbon dioxide. The mirrors could also be used to melt the ice to form liquid water, which can be used in biological reactions. Another far-fetched idea is to build factories which can release halocarbons into the Martian atmosphere. However, setting up factories that can generate a substantial volume of the gases requires a substantial amount of money as well, which is why such a project does not seem feasible to the layman. The third solution is to contaminate Mars with photosynthetic microorganisms such as bacteria. This would lead to the release of ammonia and methane as waste products, which would contribute to the greenhouse effect.

If any of these ideas or even a combination of them can be realised on Mars, it could become less hostile for humans. However, if people dream of walking around Mars without special suits and masks, they need to come up with a plan for oxygenating the atmosphere. For this, simple organisms will not be enough—large volumes of oxygen are required to support advanced life forms. Genetically engineered plants that can carry out photosynthesis in harsh Martian conditions can provide a solution. The idea is to increase the volume of gases in the atmosphere bit by bit, and as it warms up it can support more advanced plant life. This goes on in a cycle that can be continued until the conditions are suitable for humans.

However, this process would take centuries if the plan is to terraform Mars completely. Instead, "Paraterraforming" can provide a solution for the moment. Here, domes can be built to form an enclosed space that humans can live in. Microbial reactions with the carbon rich Martian soil that can give off oxygen will occur in that restricted region, but out of that enclosed sphere, life would not be supported. The advantage here is that less time and resources will be used. Carrying such a project out is not impossible; in fact, a few years ago, scientists at a company called Techshot had successfully used microbes to create a self-sustaining ecosystem within a localised region that mimics Mars' harsh atmospheric conditions.

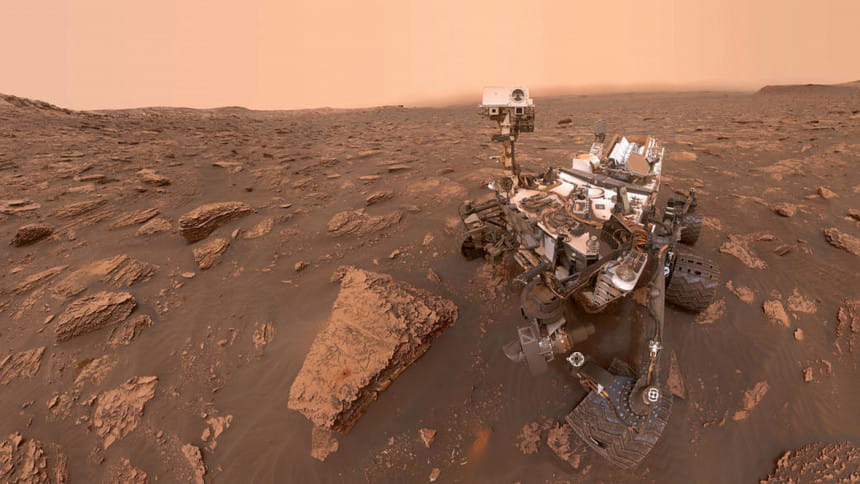

Theoretically, everything seems possible, and recent news about the conversion of carbon dioxide on Mars to oxygen by NASA's Perseverance rover is giving us hope that theories can be put to practice. At this point, landing a spacecraft on Mars with humans is a challenge, judging by the sheer amount of time it takes to complete the journey. The first humans to land on Mars will have to build the "biodomes" where further experiments can be carried out and crops can be grown under controlled conditions. Also, resources that are not readily available on Mars need to be made on Earth and imported to Mars. Are we going to be able to devote vast amounts of resources and time to such an endeavour? Will the money required for such a venture be better spent if we were to spend it on Earth? These are some of the questions that could be asked before we take on the challenge of turning Mars into another Earth. We need to keep in mind that the first step a human takes on Mars will be just that—the first step. There is a long way to go from there, and it will be interesting to see how that story unfolds in the near future.

Protiti Rasnaha Kamal holds a BA in Neuroscience from Mount Holyoke college, USA. She can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments