Fatherhood, loss, and healing in Colum McCann’s ‘Apeirogon’

On September 4, 1997, Smadar Elhanan was killed while shopping with friends when Palestinian suicide bombers detonated themselves in downtown Jerusalem. Smadar, almost 14, had gone out to buy school books. She was listening to the Irish singer Sinead O'Connor on her Walkman when she died. Ten years later, in 2007, Abir Aramin, a Palestinian girl, was shot dead with a rubber bullet outside her school. The 10-year-old had just purchased a candy bracelet from a sweetshop with two shekels her father had given her. Abir wanted to be an engineer. At school, she was good at math. She had an incredible memory that enabled her to recall verses from the Quran at will.

The first hospital the child was taken to didn't have the equipment to treat her. The ambulance carrying Abir to the second was delayed several hours at a border check-point; Abir later died in the same hospital where Smadar was born. For many years, authorities in Israel argued that Abir hadn't been shot by an 18-year-old Israeli police officer, as evidence suggested. Palestinian boys from a nearby graveyard struck her dead with stones, they claimed. In a landmark case, an Israeli court later decided otherwise, awarding Abir's family USD 430,000 in compensation.

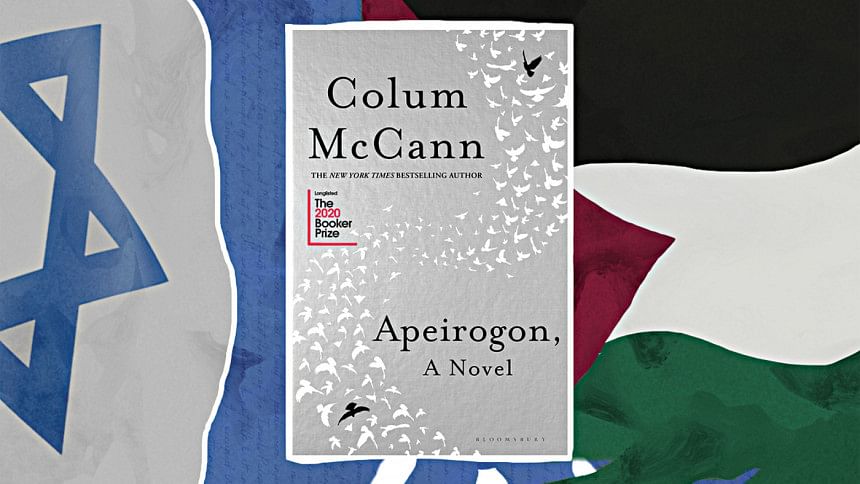

So common is the loss of children in these parts that Palestinians and Israelis both have words for grieving parents. Thaklaan for Palestinians and mispachat haskhol for Israelis are words that describe the fathers of Smadar and Abir. Rami Elhanan, an Israeli Jew, and Bassam Aramin, a Palestinian Muslim, both grew up in Jerusalem. Geography is everything in this city, writes New York-based Irish writer Colum McCann in Apeirogon (Bloomsbury, 2020), a novel that fictionalises their lives. The rapidly rising civilian death toll in Gaza this week proves him right.

McCann traces Rami and Bassam from childhood through early marriage, from fatherhood to the loss of children, from hatred to an unlikely friendship. The novel takes its name from a geometric shape that has a countably infinite number of sides and, just like its namesake, refuses to simplify the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. McCann's is a non-linear novel, with one thousand and one fragments that span hundreds of years, much like One Thousand and One Nights, the Middle Eastern classic that Rami read to Smadar every night. Some sections are just one line in length; some go on for pages.

McCann calls this a "hybrid novel" that allows him to weave snippets of history, etymology, science, economics, and politics, among other things, with Rami and Bassam's stories. We see Borges, a proponent of Israel, pontificating about literature in a souk. We learn about the accidental Chinese invention of gunpowder in the 9th century while searching for the "elixir of life." We see the horrors of the Holocaust and the American pilot Charles Sweeney circling the Japanese city of Kokura three times on August 9, 1945, unable to drop the atomic bomb because of weather, and deciding to head over instead to Nagasaki.

McCann's layered storytelling is both an intriguing and occasionally frustrating choice. It forces the reader to slow down and consider every image, scientific fact, or historical snippet on offer. By taking us across history (and the world), he helps map the Israeli-Palestinian crisis against a global narrative. We see the implications of our collective actions in the loss of Abir and Smadar. Some passages, however, including the novel's central obsession with ornithology and falconry, don't quite land. The narrative is strongest when it stays close to the consciousness of Rami and Bassam who, despite losing a child, are determined to respond with friendship and healing. It will not be over until we talk, reads a sticker affixed to Rami's bike.

In one poignant scene, Bassam confronts John Kerry with the words: "I am sorry to tell you this, Senator, but you murdered my daughter." That meeting extends beyond its allotted time, with Kerry promising never to forget Abir. For a novel documenting real grief and more than half a century of unbridled rage, Apeirogon is astonishingly warmhearted, accessible, and calm.

At the time of writing this article, on Monday, 58 Palestinian and two Israeli children had died in a fresh outbreak of hostilities, according to figures reported by Al Jazeera. As Israel ramped up airstrikes on Gaza, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who makes several appearances in the novel, has promised to keep fighting. Apeirogon is a masterful and timely literary response to this region's neverending horrors. In the white spaces of these pages, the reader is forced to face the vagaries of fate, the paradoxes, possibilities, and limitations of humanity.

Shoaib Alam is a writer and chief of staff at Teach For Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments