Life and literature in footnotes

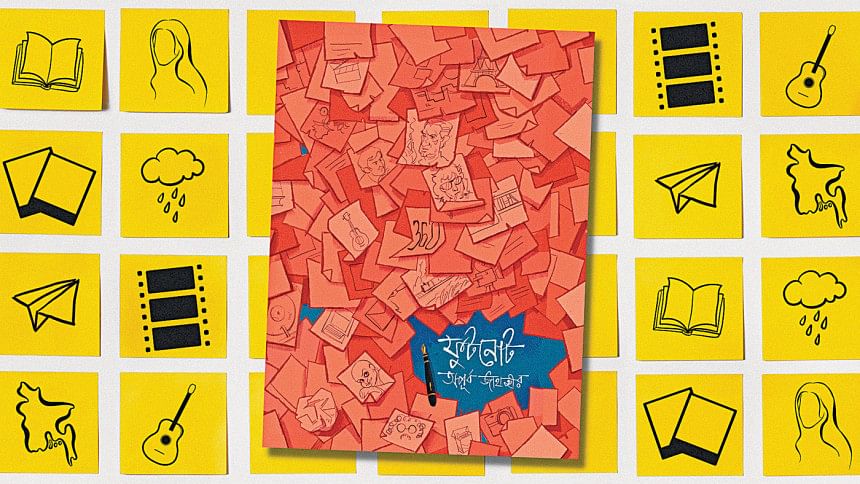

"Kichudin jabot Dhakay cholchhe prochur gorom, abar eki shathe shaolar gondho chorano brishti hochhe." The incessant heat and rainfall, the month of May, the lull of Eid holidays and the call of books, films, and music are just some of the elements that make Apurba Jahangir's Footnote (Subarna, 2021) a fitting read for this time of the year.

I'd be lying if I said I was always fascinated by footnotes as a reader—part of my thirst for the taste of prose meant that I was always in a hurry to devour the text proper, and any notes and annotations on the page felt like impediments standing in my way. At some point, however, the blank margins in books began drawing more and more ink from my reader's hands, and the more ideas that I poured onto those spaces, the more I realised that footnotes tell their own stories. Working as an editor has only heightened this appreciation. As anyone who has ever edited a text will know, sometimes the most interesting details are the ones we have had to prune to fit into the straitjacket of a word limit. Including these details as footnotes is an exercise in democracy, in acknowledging that what doesn't fit into the preferred narrative of the author might still be of interest to other readers.

In his upbeat, humble collection of musings, Apurba Jahangir brings these annotations to centre stage and lets them breathe. "When I was 10 years old, my father [Muhammad Jahangir] instructed me to write about any new place I'd travelled to or any new book I'd read", he shares in his preface, recalling also the early influence of Toitumbur magazine. "As my first ever editor, father asked that my writing come from a place of personal reflection, and that it end with me forming an opinion". This attitude forms the central premise of Footnote as Jahangir—sidestepping the promise of "analyzing" anything—reflects rather on the books, films, and music that have shaped his journey through life.

Through his musings we revisit historical icons like Bob Dylan, Satyajit Ray, Rituparno Ghosh, Ritwik Ghatak, Jibanananda Das, and Sunil Gangopadhyay, with the ghost of Tagore ever-hovering over the horizon. We meet, as well, contemporary Bangladesh, for which he recalls uniquely relatable experiences of everyday life, like watching pedestrians from the Kawran Bazar overpass and listening to the music of Elita Karim, in whose band the author performs as guitarist. In one of the most endearing scenes in the book, Jahangir runs frantically between the aisles of Baatighar Dhaka as rainfall chimes against the windows. Fourteen books are placed at the counter, the bill is already Tk 3,000 over his budget, and yet the work of Sanjay Ghosh calls out to him from the shelves only because it comes recommended by Jamini Roy. "Shotti, ekkhan dokan baniyeche bote Dipankar Shaheb", he writes of the bookstore's owner. "Dipankar has really created something special."

None of the very short chapters aspire towards film or literary criticism, but even as personal reflections, they cast a discerning eye on life and art as it unfolds around the author. In a gesture that feels as generous as it is whimsical, Jahangir is interested in the city as character—Dhaka a city of obhimaan, at once a confused youth and a voice decaying and bursting from repression. There is room, too, in the book for more serious ponderings, as the writer looks to do away with labels and hierarchies. He questions the limiting effects of outlining genres in music—what separates "band" music from baul song?—and in teasing out the nuances that we form in our relationships with authors. Reading Tagore throughout a solitary life turned Rituparno Ghosh into a devoted friend of Rabindranath as a reader, Jahangir points out, not into a fan.

While these insights ring sharp, they accomplish the feat of brevity by often assuming that their readers are intimately familiar with the books and films being discussed. What's wonderful is that none of this comes across as pedantry. True to the definition of its namesake, Footnote manages to pique one's curiosity with nuggets of facts and ideas, and the informal, cheerfully self-deprecating style of writing paints the portrait of an author who seems, above all, to have fun with reading, watching, and thinking about art. The book speaks volumes, but it never lectures.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or

@wordsinteal on Twitter and Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments