Changing mask-wearing norms is no easy task, but it is possible

Getting people to wear masks consistently is no easy task. Both BRAC and Yale University researchers have independently tracked mask-wearing across Bangladesh for months, and it has never remained stable. So a team from Yale, Stanford, the NGOs Innovations for Poverty Action and Green Voice, in partnership with a2i and BRAC, set out to rigorously identify how to change community-wide mask-wearing norms.

The researchers iteratively experimented with over a dozen strategies that they thought could increase mask-wearing, and tested them using a massive randomised controlled trial involving 350,000 adults in 600 unions in rural Bangladesh. They identified a precise combination of four strategies that are successful in changing norms. When jointly implemented, these strategies tripled mask wearing. And the effects were persistent: Mask-wearing remained consistently high for over 10 weeks or more, including a period after active interventions ended.

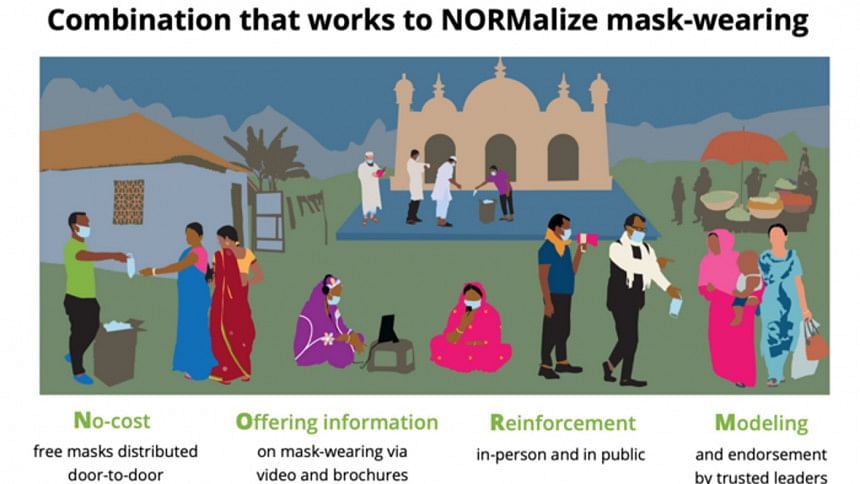

These four strategies formed the basis of a model we call NORM because it appears to change social norms around mask-wearing: No-cost mask distribution, Offering information on mask-wearing, Reinforcement in-person in public spaces, and Modelling and endorsement by local leaders. The NORM intervention also increased physical distancing and was especially effective when implemented with the support of Imams before Jummah prayers.

Engineers at Stanford designed two different high-quality masks for the project using materials widely available in Bangladeshi RMG factories: a cloth mask and a surgical mask. The surgical masks proved to be the winner. They are one-eighth the cost, they have much greater particle filtration efficiency, and they are washable and reusable. Laboratory tests at Stanford and in India show that their greater efficiency is retained even after the mask is washed 20 times with soap and water. Study participants also preferred the surgical masks, especially as the weather got hotter and more humid. These masks can be produced very cheaply and quickly during pandemic waves: Millions of masks can be machine-made daily at only Tk 5 per piece.

Combining the Bangladeshi expertise in behaviour change at Yale, the Stanford Medical School expertise in mask design and public health, and efficient implementation across Bangladesh produces this frugal indigenous innovation that changes masking norms quickly and saves lives in a very cost-effective way. The results from this study were so compelling that this Bangladeshi innovation is already replicated globally across India and Pakistan, and even in Latin America, and drawing headlines like "India Draws Lessons from Bangladesh's Mask Study."

Decisive action from Bangladeshi leadership was also critical for scaling. The mayor of Dhaka North City Corporation heard a presentation from the research team seven days before Eid, and immediately mobilised a consortium of partners to implement the NORM model in the next 48 hours at shopping malls and transit hubs all over Dhaka North, to stem the flow of Covid during the Eid travel rush. He personally modelled the critical R ("reinforcement") part of NORM, by going to the field and reminding people to wear masks.

To avoid the devastation that India is currently experiencing, masking norms need to be changed nationwide in Bangladesh. This requires further innovations in scaling quickly, which BRAC is well-poised to do, as they have done in the past with many flagship public health and development programmes. The researchers have joined forces with BRAC to leverage its trusted community health worker networks to reach over 77 million Bangladeshis with the NORM model quickly. The data suggests that getting people to wear masks consistently at this scale—which exceeds the entire population of the United Kingdom—could dramatically reduce Covid-19 transmission, and ultimately save thousands of lives in Bangladesh and globally.

BRAC is also creating livelihood opportunities for local artisans by procuring cloth masks for the ultra poor to complement the other masking activities. They are also mobilising teams of volunteers and helpers at warp speed to aid its Shasthyo Shebikas and Shasthyo Kormis to conduct all the activities the NORM model requires: door-to-door distribution of masks, engaging community leaders, providing information and inspiring rural residents, and reinforcing the importance of masks by politely intercepting non-mask-wearers in public spaces. But we need to form broader coalitions to be maximally effective. Large quantities of masks need to be procured, for which the government and business leaders can play critical roles. We had to rely on the generosity of some individual donors to procure millions of masks to scale up quickly in India.

The programme offers a very cost-effective way to save lives. It can save the economy hundreds of crores by reducing the intensity and duration of required lockdowns. BRAC, in partnership with Canada, is already investing a large amount of its own human and financial resources to reach 77 million people. The remaining gap is in procuring 55 million more reusable surgical masks (at a cost of USD 3 million) to implement the evidence-based strategies, change norms, and stem the spread of infections. Epidemiological data and modelling suggests that this would save around 15,000 Bangladeshi lives over the next few months. That's an absurdly high-return investment for any government, donor, or business leader.

How else could you save a life for an investment of only USD 200 or Tk 17,000?

Mushfiq Mobarak is Professor of Economics at Yale University. Asif Saleh is Executive Director, BRAC.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments