Tremors in Sylhet might hint at bigger earthquakes

In two days (May 29-30), six successive mild earthquakes shook Sylhet city and its adjacent areas, leaving people panicking and running out into the streets. The Bangladesh Meteorological Department confirmed that one of the tremors was of the magnitude of 4.1 on the Richter scale. On Monday, Sylhet was jolted by another mild earthquake. In the meantime, Sylhet City Corporation sealed off 24 vulnerable buildings for 10 days after the series of tremors caused a building to tilt. One must question why it took so long for this action—specialists from the Shahjalal University of Science and Technology had flagged 35 buildings as vulnerable to earthquakes almost six years ago.

Bangladesh has not experienced a major earthquake in over a century, since the 8.1 magnitude Great Indian Earthquake in 1897. At the time, 545 buildings collapsed in Sylhet district and a large number of people died, even though the population density and number of concrete structures were far less back then. However, an escalation in seismic activity has been observed recently. A magnitude 6 earthquake was felt on April 28 this year. Three earthquakes were felt in 2020—a magnitude 4.4 on November 3, 5.8 on June 22 and a magnitude 5.1 earthquake on June 21.

Experts say that in earthquake prone areas, earthquakes occur more after every 100 years, and Bangladesh is situated in a high risk zone for earthquakes. The observatory at BUET recorded 86 tremors over four magnitudes during January 2006 to May 2009. These minor tremors indicate the possibility of heavier quakes.

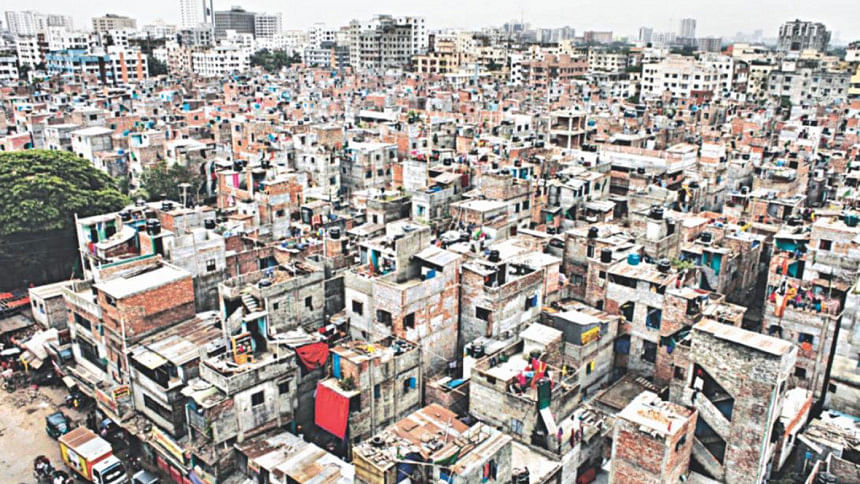

Dhaka is more vulnerable to earthquakes due to its geological location and human and economic exposure. According to the earthquake disaster risk index, Dhaka tops the list of the 20 most vulnerable cities in the world. According to a seismic zoning map from BUET, 43 percent of Bangladesh can be rated as high risk, 41 percent as moderate and 16 percent as low risk. The high risk group includes major population belts such as Chattogram, Dhaka, Rangpur, Bogura, Mymensingh, Cumilla, Rajshahi and Sylhet.

A study from the Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme (CDMP) suggested that some 72,316 buildings in the capital will be fully damaged and 53,166 others will be partially damaged in the case of a 7.5 magnitude earthquake, leading to an economic loss of about USD 1.1 billion from structural damage only. At least 10 major hospitals and 90 schools in the capital may be destroyed completely and another 241 hospitals and clinics may be partially damaged. Economic loss due to damage of structures is likely to be USD 1.07 billion in the case of a magnitude 6 earthquake. It took 21 days to complete the search and rescue operation of the tragic Rana Plaza collapse. If a single building can take that long, what will happen if a moderate earthquake hits the city and the estimated damage occurs?

The government of Bangladesh has already taken a number of initiatives to minimise the potential damage of a sizeable earthquake. By analysing the seismic data, earthquake risk maps of Dhaka, Chattogram, Mymensingh and Sylhet City Corporations were prepared, and similar mapping projects are underway for some of sub-regions. The Standing Orders on Disaster (SOD) were updated in 2019, where responsibilities were defined according to relevant ministries, departments and agencies to reduce risks and damages. Ward level disaster management committees have also been introduced.

Additionally, the National Contingency Plan has been prepared for emergency response agencies, including the Fire Service and Civil Defence (FSCD), Armed Forces Division, Department of Disaster Management and Cyclone Preparedness Programme. Finally, the Ministry of Housing and Public Works has been able to get approval for the National Building Code after five years of delays. Back in 2012, CDMP built a team of 62,000 urban volunteers to carry out immediate rescue operations if disaster occurs. This programme was then handed over to the FSCD. The government has also spent Tk 62 crore to procure search and rescue equipment, and has handed it over to concerned agencies.

However, although the government has taken several initiatives, this level of preparedness is not enough with respect to the country's vulnerabilities, which was demonstrated in the Rana Plaza rescue, as well as during recent fire incidents in Banani, Chawkbazar or Nimtoli. Our citizens have immense gaps in knowledge when it comes to how they should act during earthquakes. Out of 62,000 urban volunteers created by CDMP, only around 37,000 been trained by FSCD and the programme has all but disappeared. The volunteers who are trained are not on track, although there was a plan to develop an inventory and organise refreshers on a regular basis.

A lack of coordination among responding agencies is the biggest obstacle. There is also not enough engagement of NGOs and the private sector in response mechanisms. For example, debris management will be a big issue if an earthquake hits. The Rana Plaza collapse generated around 7,000 tons of debris. If we see an earthquake like that of 1897, about 300 million tons debris will be generated and the first task would be to clear the roads leading in and out of cities before any rescue drive could commence. However, despite the scale of these tasks, contingency plans are yet to be tested and standard operating procedures for agencies are yet to be developed. A specific authority and implementation plans are yet to be placed for acting building codes. The narrow and crowded road in the capital, such as in old Dhaka, would be a serious bar to future rescue operations.

So what can we do to ensure that we are ready to manage the worst case scenario, in the event of a disaster? First, a coordination platform should be in place, involving different government and non-government agencies. Additionally, extensive mass awareness programmes must take place on a regular basis and span all strata of society, including city dwellers, government officials, municipality officials, politicians, engineers, architects, designers, builders and medical people.

Secondly, the government must enforce proper implementation of the National Building Code. Experts have continuously pointed out the need for a proper implementation plan, as well as an authority nominated to oversee implementation of the building code. Initiatives should be taken to demolish old and high-risk buildings as a first step towards minimising casualties, followed by retrofitting to make vulnerable buildings more resilient.

Finally, capacity enhancement of emergency response agencies is a must in the areas of both skill and equipment. Coordination amongst the agencies should be the top priority. Disaster risk reduction measures should also be institutionalised at community and household levels. In this, both public and private sectors should be more involved. In the area of mass awareness, the systemic engagement of the media could play a vital role.

It should be said that we are not expecting a big tremor in our country any day now, but if it does strike, only the development of a culture of resilience can contribute to reducing the loss of lives and property.

Mohammed Norul Alam Raju is a development practitioner. Email: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments