Remembering the Birangona: The power of personal narratives

In Bangladesh, the invocation of the Birangona, "war heroines" who expeirneced sexual violence in 1971, produces an image locked in time with no past or future, symbolising them as sites of violence and conflict. It is an image which, over the course of 50 years, has been commemorated or suppressed by powerful actors—the state and communities—with varying degrees of success. The telling and retelling of the Birangona narratives were critical to the meaning-making of the Liberation War of 1971. Retaining specific accounts of sexual violence or the significance of the statistical burden of victims have been recalled time and again as the nation sought to recover from the miasma of its history. But looking deeper into these oral histories provides us with documentations of how the state, communities, and families dealt with the outcomes of violence and the kinds of vulnerabilities these women faced afterwards. Within the patriarchal structure that the state, community, and families embody, how these narratives and their historicity came out and lived out depended on a plethora of power dynamics, current events, and political priorities.

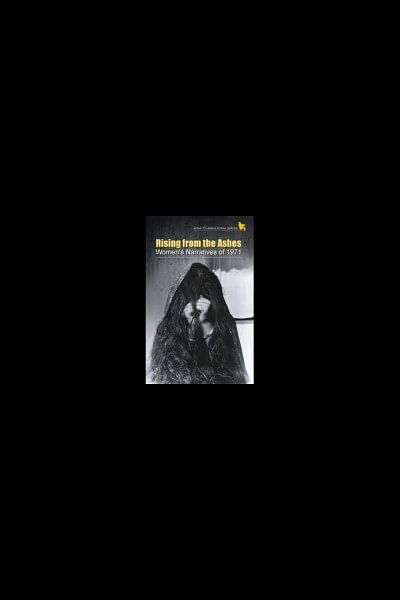

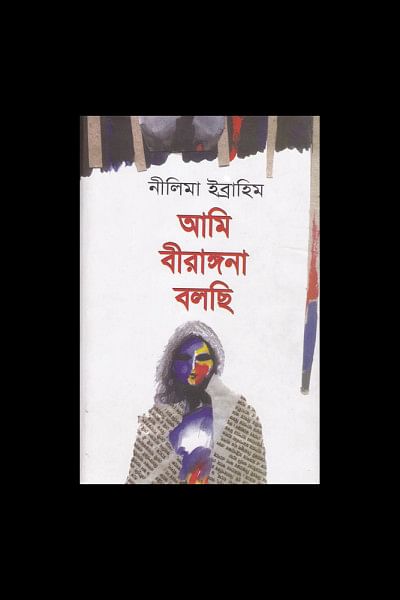

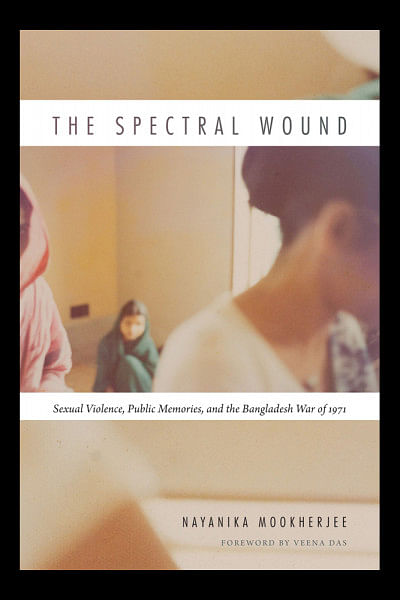

The books we recall today, Ami Birangona Bolchi (1994), Rising from the Ashes (2001), and The Spectral Wound (2015), are among the documentations which highlight women's voices and their perspectives of 1971. These three books focus on the memories of wartime violence against women (and men) and the aftermath of that violence in terms of their lived experiences, and the responses they received from families, from the community, and the government.

Personal narratives have a transformative power and these books have done the critical work of conveying stories while drawing out nuanced understandings of how acts of violence permeate their everyday lives, memories, and bodies.

In our collective memories, we see the Birangona from a distance, we commemorate their bravery and resilience, but fail to recognise or engage with the wound that they have to live with. In Rising from the Ashes (2001) edited by Shaheen Akhtar, Sultana Kamal, Niaz Zaman, Hameeda Hussain, Suraiya Begum, and Meghna Guhathakurta, the authors weave together the present and past. It is written in third person, with first person quotations by the women narrating their experience. This is interspersed with observations on their body language and critical historical and geographical backgrounds.

Years after the violence and trauma of '71, the events are still alive in their bodies: "Hands tremble, voices shake, and wounds that may have been healed reopened". Women narrate with tears, gripping hands, and long pauses, a phenomenon that years later Nayanika Mookherjee would dissect in Spectral Wound (2015).

Mookherjee's exploration centres on the stories of four women and their "severe histories", a body of research described as "a triangulation of Birangona narratives, activist discourse, and literary and visual accounts." The most powerful argument that Mookherjee makes is the reiteration of the wound—the bodily experiences cited by the Birangonas and the people with whom they live are not the effects of past events but are rather triggers of memory. The violence experienced by Birangonas still exists in the places and in the relations in which they live. Everytime this violence is remembered—through an unexpected clap of thunder, the sight of a broken wall, or a particular sensation on the skin—it activates their memories of violence. "We must tell these narratives," Mookherjee insists, "in order to communicate how people fold the violence of wartime rape into everyday sociality". By writing, speaking of, and publishing these oral histories and research work, women reclaim some power over the narratives that have been used over and over by state and other actors.

Mookherjee and Niaz et. al. remind us that recognition of violence and pain requires more than being invoked and exalted. We need to do more than putting the survivors on a pedestal and explaining their entire personhood through memories of particular acts of violence. It requires compassion, trust, and an understanding that violence and violation does not decrease a person's dignity nor does it seek to be glorified. The narratives of the Birangona extend beyond their remembrance as suspended war memories. One should ask themselves—how have we remembered the legacy of the Birangona? Have we forgotten the women and relegated them to the margins of their own narratives?

That is where Ami Birangana Bolchhi (1994) comes into retrospect. Dr Nilima Ibrahim writes a fictionalised account of true events narrated by Birangonas themselves; the accounts that she got to hear firsthand when she visited a group of Birangonas leaving the country with the Pakistani war prisoners, and later on when she worked in the rehabilitation centre set up by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman regime for Birangonas. In this regard, Ami Birangona Bolchhi stands out, as it digs deeper, on a personal level, into how the war, the inflicted violence, and the subsequent trauma affected these women's lives, against the backdrop of the socio-political reality of the time.

These personal narratives reflect how patriarchal norms and social expectations of honour and shame made women who lost families, livelihoods, and homes even more vulnerable. They were questioned on their integrity and blamed for their fate over which they had no control. A war-torn nation venerated its sons for being on the frontline of the war but assassinated the characters of its daughters who made immense sacrifices as well, in many cases resulting in more severe implications on their physical and mental well-being.

Losing their rights to self-recognition in a newly-freed country, the crisis of identity haunts a Birangona for the rest of her life like an unwanted, omnipresent shadow. In Ibrahim's novel, Tara Banerjee, who migrates to Europe, establishes herself as a brilliant medical professional, falls in love and starts all over again, comes back to the country many years later as Tara Nielson, and is venerated by the same family that once disowned her for her sufferings. At that moment, she realises that this country will never be her home again, and she is not accepted because of the Tara inside her, but because of her new identity as Mrs T Nielson. The same goes for Meherjaan, who marries a Pakistani soldier and migrates to Pakistan, holds her Pakistani passport and introspects the same. The state that venerated these women and their sufferings had also been responsible for adding to their vulnerabilities and for pushing them to renounce the identity of that very same nation.

Ami Birangona Bolchhi narrates the struggles of women from different socio-economic and familial backgrounds and connects them through a common thread. Many of them had to leave their homes, migrate after being disowned by their families and religious communities. Similarly, Farzana and Rumana's stories in Rising from the Ashes depict how they were unable to find a home to rent because landlords would question the morals of two unmarried sisters. Such patriarchal dogma exists to this day.

Why are character certificates important even in a time and context where a community is reeling from the aftermaths of bloodshed?

These books serve as a reminder that research can take the form of resistance and solidarity. In their own unprecedented ways, these books offered a space to the women to develop meaning and understanding of their experiences. It was a narrative practice that openly challenged the oppression and the patriarchal gaze of war from which violence had borne. The spectrum of narratives offered in these books and the insightful analysis accompanying them commemorates the resilience of the Birangona and demonstrates that the onus of power that shapes these narratives takes place beyond the bodies and histories of the Birangona.

Ishrat Jahan is an early stage researcher who writes in her free time. You can follow her on Twitter @jahan1620.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is a sub-editor at Toggle, The Daily Star.

For more book-related news and views, follow Daily Star Books on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments