A tribute to my father and his bookshelf

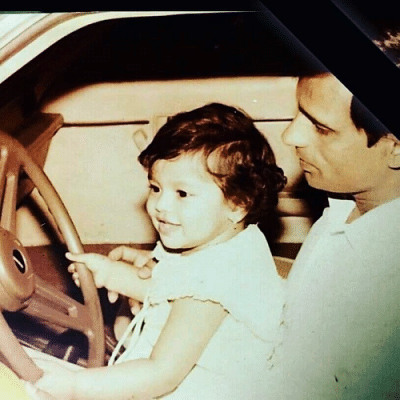

Last week, we marked the 10th year of my father's death, on June 15th. Every year since we lost him, I would make it a point to post little stories about him from my childhood, on social media. I call them #memorydoodles. This year, while posting pictures and posts about my father, memories of Abbu – his bookshelf and the many books strewn all over our home – rushed in and I found myself remembering all the moments we shared around books.

I grew up in the 90s, when reading a book was not a glamourised occupation; it was a normal and a regular activity. Every home would have a bookshelf, stacked with the mandatory classics, comics of all kinds, magazines from years ago and of course some of the contemporaries as well. Individuals from an all-worldly background would also have biographies of tycoons like Marriott, while the trendier ones would treasure their Stines, Crichtons, Sheldons and romances by McNaught, Steele and Garwood. We were no different. From one single bookshelf that belonged primarily to my father, eventually, adding one more where my siblings and I could stack our favourites as well, we ended up with at least three.

Raised with many siblings in the village of Uttar Madarsha, Hathazari in Chittagong, my father belonged to humble backgrounds, working hard all his life to achieve his dreams. Not only did he complete his Master's in English in 1975 from University of Dhaka, he also managed to travel to the Middle East and start a career as an English teacher in 1978. In 2010, he retired as a Senior Lecturer from the King Faisal University in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In 2011, Mohammad Nurul Karim, my father, at the age of 62, passed away due to a surgery that had gone wrong. One can only imagine his passion and enthusiasm for literature, old writers, poets and of course books.

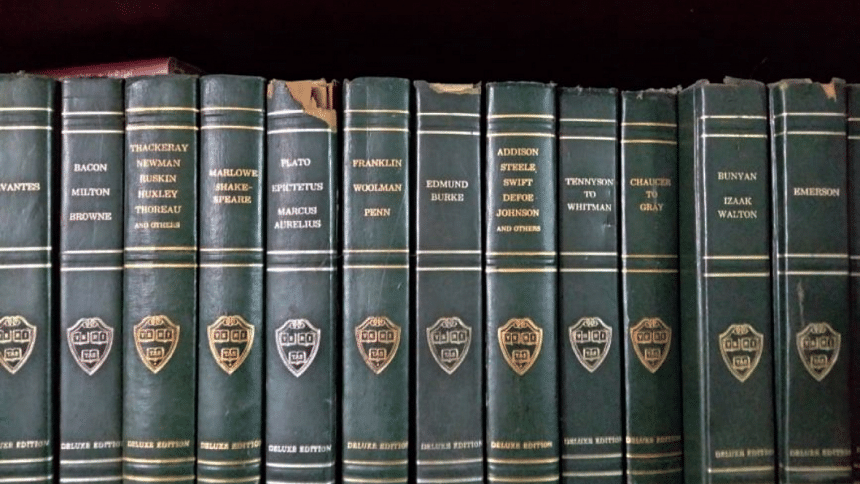

Abbu's shelf was filled with books and magazines of all kinds. One particular rack in his shelf was dedicated to a series of books on essays, written by world famous philosophers and thinkers. Even though we were allowed to go through his books and magazines located on the other two racks, there was an unspoken rule about not touching the rack with the essays. The books were an intimidating lot – bound in black, titled in small gold letters. Clearly, they were more than a century old. I would always wonder about the origin of these books and why my father would keep them in his collection. Abbu actually brought these books back and now they're showcased nicely on the top rack in my bookshelf. I still get the chills when I see them!

Those were the times when magazines would make a lot of money. Today, bringing out a magazine and subscribing to one every week is probably more of a novelty and in fact, a luxury for most, due to everything going digital. Back then, however, subscribing to magazines and actually saving up for the publications more suited for teenagers was normal (yes, I am talking about myself!) I remember Abbu treasuring one particular brand of magazine called Forum – more like a journal for English teachers. We had many issues of Forum lying around all over the house. An avid reader as a young child, I would read anything and everything that I could put my hands on. Surprisingly enough, Forum also became one of my sources of enjoyment. Abbu took pleasure in the fact that I was reading the publication (which I would have found extremely boring if I were to read one today), instead of some of the "trashy ones" that I subscribed to – the sort with rock musicians and boy bands on the front covers.

Bangladeshis who grew up in the pre-independence era, till a good part of the 90s even, might remember a massive red English grammar book – a Holy Grail for most English teachers and young students practicing English, reading and writing. This particular book had a special place on Abbu's shelf. The cover all torn; the pages withered with age. But I still couldn't help feeling excited every time I read it, from cover to cover. I think I read it at least 15 times! I still remember one particular essay from the book where the writer discusses the advantages and disadvantages of having television at home. Since the book was probably published at a time when the television was still new for many families in Bangladesh, it talked about how insulted visitors would feel, if they chanced upon the family (they were visiting) all watching TV together. Surely, this would put a strain on Bangladeshi hospitality, which was why a television set should never be allowed inside a family home!

Abbu lived in the world of Rabindranath Tagore and William Shakespeare. He owned one of the earlier versions of the Gitabitan, a book of songs and poetry by Tagore. That particular book also had a red cover, however, it felt smooth to the touch. Inside the book, Abbu would write little notes in pencil, next to lines of songs he probably liked. Many of his favourite songs would be marked, which he would sing over and over again on the harmonium. In 1995, on our first visit to England, Abbu had just one wish: to visit the Oxford University and visit Shakespeare's museum. I wish I could find the pictures where he and my uncle, all dressed up in suits (in summer) and polished shoes, posing in front of the university gates, the libraries, even some of the souvenir shops. He posed in front of a board with William Shakespeare's name etched on it; just the way he was instructed to by my mejo khalu. Holding on to the signage, looking into the lens and feeling proud.

A sharp and well-informed individual about both deshi and global politics, Abbu had lots of publications on current happenings and history. At a typical adda, my soft-spoken father could converse for hours together on the history of the country and the ongoing political changes taking place in Bangladesh. He also read voraciously on national politics, which led him to write his thoughts in diaries that I found years later and have them safely tucked in with my other valuables.

Like Bangladeshi Muslims, we also had copies of the Quran in the house, but not wrapped up in special paper and cloth, stacked up high so as to keep it safe from evil eyes and intentions. In fact, Abbu would keep translations, beautiful inscriptions of the scriptures and stack them up on the top rack, with his intimidating set of philosophies. He had also piled up newspaper cut-outs of write-ups by different scholars, discussing ideas in Islam, which his generation otherwise had grown up thinking to be wrong.

Young readers today would refuse to believe this, but there was a time when parents would actually ground kids for reading too many books and ignoring their school work! This was quite regular in our household. I still remember that scary evening when Abbu stormed into my room, trying his best not to scream and vent – my teachers called him to school and told him about how I was neglecting my studies and was spending all my time reading fiction and contemporaries from the library. They even shared some of the class test marks with him, which I had probably "forgotten" to show my parents, conveniently. My father actually asked my teachers to not allow me to borrow or issue any more books from the library till after my board exams. Did that stop me, though? No! Thus began my long trips to the bathroom, carrying books and hiding them inside my clothes. Come to think of it, one of the most comfortable places that I could imagine myself reading a book in peace would be the small space near the door, inside the bathroom, right next to the laundry basket and the washing machine. The second most peaceful place was under the blanket, with a torch, at 3 in the morning, until of course I got caught by both my parents. Needless to say, even though my family poured me with love in the form of books, reading did get me into trouble several times.

Needless to say, Abbu would always buy books for children on their birthdays. They were the most useful and the best present one could ever have. Even today, my friends, with kids of their own, talk about how the wrapped-up birthday presents from their Karim uncle would be so predictable – books!

My father's love for books and maintaining a well-rounded bookshelf did rub off on me, and I believe that this is one of the best legacies that one can leave behind in this world.

If my father is reading this – may you be happy, relaxed, content and resting in peace, wherever you are. I love you, Abbu!

Elita Karim is a journalist, musician, and editor of Star Arts & Entertainment and Star Youth, The Daily Star. She tweets @elitakarim.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments