Have we done enough to address the problem of drug abuse?

On May 27, The Daily Star reported that detectives had claimed to have seized LSD, an extremely potent hallucinogenic drug, for the first time in the country during a raid in Dhaka. Three days later, the newspaper published another report that described how LSD has been smuggled into Bangladesh from the Netherlands since 2017 using the government's postal service.

A number of reports have recently come out on this topic, mostly due to the much-publicised death of a university student who allegedly killed himself under the influence of LSD. But why did it take four years for the law enforcement agencies to finally wake up to this threat? What (or whom) were they under the influence of?

This series of events perfectly describes the main problem when it comes to drug abuse. We as a society often say that the best solution to drug abuse is greater awareness. But awareness for whom? Only the users?

The theme of this year's International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking is "Share Facts On Drugs, Save Lives", which aims at promoting and sharing the realities on drugs: "from health risks and solutions to tackle the world drug problem, to evidence-based prevention, treatment, and care".

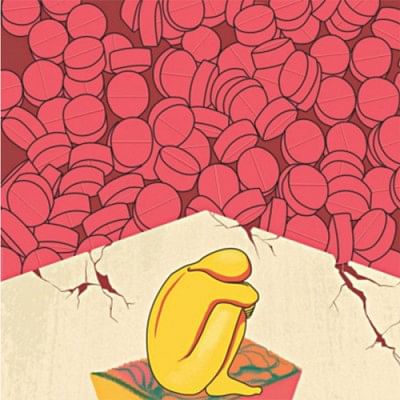

Well, here are some facts: According to data from the Department of Narcotics Control, total seizures of yaba pills in Bangladesh went from being 36,543 in 2008 to 812,716 in 2010, 1,951,392 in 2012, 6,512,869 in 2014 to 29,450,178 in 2016—which indicates that despite the availability of drugs like marijuana and heroin, yaba (a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine) continues to be the most prevalent drug in the country. And unsurprisingly so, as over the last 10-15 years, increase in the use of methamphetamine globally has outpaced that of any other drug. Meanwhile, it has been said, both officially and unofficially, that other deadly drugs such as cocaine, ice and LSD (recently confirmed by law enforcers) have also started to enter into the country.

Due to the lack of data, the number of drug addicts in Bangladesh continues to remain unknown. However, estimates (that are somewhat outdated) range from 100,000 to 4 million. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the incidence of drug abuse during the pandemic has shot up worldwide, just like it did following the 2008 global financial crisis.

The fact that this has happened is quite revealing. It reveals something very important about the demand side of the drug problem: that drug use is fuelled largely by various social factors such as poverty, isolation from friends and family, loneliness, desire to escape from stress, peer pressure, etc. Although many researches have revealed this to be true, in our society, this is barely accepted or understood. As a result, the way we deal with drug addiction or drug users often turns out to be counterproductive.

People who are addicted to drugs need empathy and love to overcome their addiction. These are the two most common threads—along with professional help—that can pull them out of the quagmire of addiction. Unfortunately, there are not enough reliable rehabilitation centres in our country, and most are out of the reach of lower- and middle-income groups. At the same time, we must do more to prevent people from getting addicted in the first place by ensuring that they do not feel alienated from their friends and families or their community. Involving people in social/community activities, therefore, is crucial.

In Bangladesh, young people tend to become dependent on drugs the most. But what is driving them towards addiction? Alienation, depression, and an inability to relate to community and culture could be some of the reasons—problems that are much bigger than drugs, but are leading towards their usage. People in general, and young people in particular, have to believe that they have a purpose to their lives. In the absence of such belief, people tend to get involved in self-harming activities, despite knowing the dangers that these activities pose to their lives. And this is where we have failed.

We have failed to understand the drug problem at a much deeper level than just this, however. For years now, we have seen the government wage its war on drugs, leading to the loss of hundreds of lives and incarceration of small-time dealers and users. Yet, it has failed miserably to stop drug use. That is not only the case in Bangladesh; we have seen other countries (the US, for example) wage similar drug wars, but to no avail.

Bangladesh is a country that has always suffered from the curse of poverty. This means that there have always been people desperate enough to become small-time dealers to survive. Going after these people, killing them and jailing them cannot stop the supply of drugs. That should be obvious. The only way to reduce the supply is to go after the real kingpins. Why haven't the authorities done that?

The only explanation for such failure is that these masterminds are well-connected and protected. Consequently, the drug trade is among the most lucrative businesses in the world, meaning that paying off people in power to continue looking the other way happens frequently when it comes to the drug trade. Because of that, it is often connected with other crimes such as human trafficking (mostly to force people to traffic drugs). Which also explains why major drug cartels around the world are often found to be involved in trafficking people. But given the lack of accountability and transparency in our governing system as a whole, identifying and punishing those who are really behind the supply and trafficking of drugs (and people) is no easy thing to do.

Nevertheless, if we want the curse of drugs to stop plaguing our youth and our nation, it is something that must be done. The real masterminds behind the supply of drugs must be identified and punished. On the other hand, by learning from the likes of Portugal, which has addressed the drug problem most successfully, we must be more lenient towards its users by passing law that removes incarceration for drug use—although people caught possessing or using illicit drugs may be penalised by regional panels made up of social workers, medical professionals and drug experts. The panels can refer people to drug treatment programmes, hand out fines or impose community service, which once again should aim to involve people in community activities.

The problem of drug use is not a problem exclusive to Bangladesh. Every country around the world has faced it. Some of them have done so successfully, others have not. We must stop emulating the countries whose drug policies have failed to stop or reduce drug addiction, and start adopting policies that have actually worked. Otherwise, it cannot be said that the policymakers are not equally culpable for the rapid explosion of drug use that we see in Bangladesh, and the enormous social costs and sufferings that come with it.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

His Twitter handle is: @EreshOmarJamal

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments