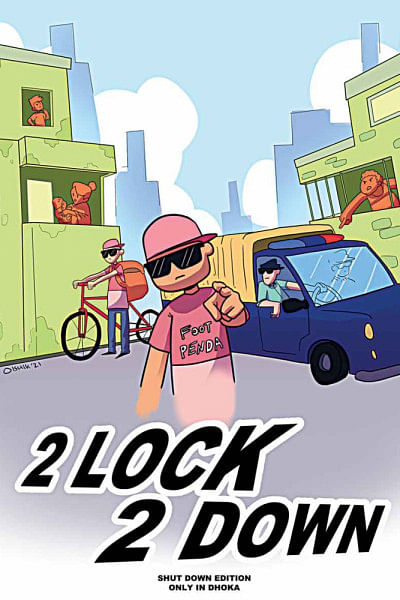

Words don’t matter: Linguist concludes after researching ‘restriction’, ‘lockdown’, ‘shutdown’ and ‘holiday’

Loam Chomchom, a local linguist, recently published a peer-reviewed article in an international language-sciences journal following months of research during the pandemic.

The research was based on language and its myriad applications used by policymakers in Chapasthan during the Covid-22 pandemic.

Chapasthan had previously earned worldwide linguistic paradox fame following an opposition party's months-long blockade and "hartal", during which life went on as usual.

This correspondent got hold of Loam Chomchom after two months of repeated emails and phone calls for just a five-minute interview because yours truly is bad at math and could not calculate exactly what 14:30 meant.

"It was not until the pandemic had continued for a year and policymakers were enforcing public holidays -- which really meant everyone should stay at home -- or strict restrictions, or shutdowns where markets were open but schools were shut, that the idea struck me: to really look at the nature of these words and what it meant to the public," said Chomchom, visibly annoyed that I was over an hour late.

He calmed down when I told him an on-time Chapasthani was right up his alley of linguistic paradoxes.

"The Chapasthan policy-makers first imposed a public holiday when the Covid-22 virus was very new and people were terrified, so they actually did not celebrate no holiday but stayed at home. But by the end some people caught on to it and rushed to the beachside town to observe the public holiday. Here is what one of my respondents had to say when I asked him why he took his entire family for a vacation in the middle of a pandemic: 'God will protect us, we have left the matter up to God and I have read that the virus does not spread much outdoors, plus our very own government, who we trust so much, did call this a public holiday. What does one do during a holiday?'"

The real confusion started when the pandemic rolled on to another year and people starved for entertainment were put under what the government called "strict restrictions on movement". For the first week, everything looked serious, everything was closed but soon enough the government opened up malls because Chapasthan's biggest festival was around the corner.

So, people were confused yet again. "Do they go shopping? Do they now go shopping while maintaining strict restrictions? And how do they go? Public transport was closed. Did these restrictions apply to only those who were poor and needed buses because those with private cars were zooming by?" asked Chomchom.

The restrictions then gave way to a "shutdown". That continued for a while, always with a window in between for people to rush out of the city. With days to go before the shutdown ended, the government then imposed a "strict lockdown". But to bridge the gap between the shutdown and the strict lockdown, they imposed an "interim lockdown" during which people could shop for toothpastes and shower gel, but not for shoes and mobile phones.

"What do these terms mean?" asked a confused Chomchom, who had made it his life's work to explore the relationship between signifiers and signified.

When the "strict lockdown" eventually went into effect, people were detained for going out because some thought it would be similar to a previous "lockdown" and others thought it was a "holiday" and wanted to see how it was going, because they did not have other sources of entertainment.

"It is my conclusion, after a lifetime of research, that words do not matter," said Chomchom, and thanked me for being so punctual.

Email your satire pieces, cartoons, cartoon strips or whatever tickles your funny bone to [email protected], and you too may have something to show for wasting your time

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments