The universality of solitude and good books in Jhumpa Lahiri's 'Whereabouts'

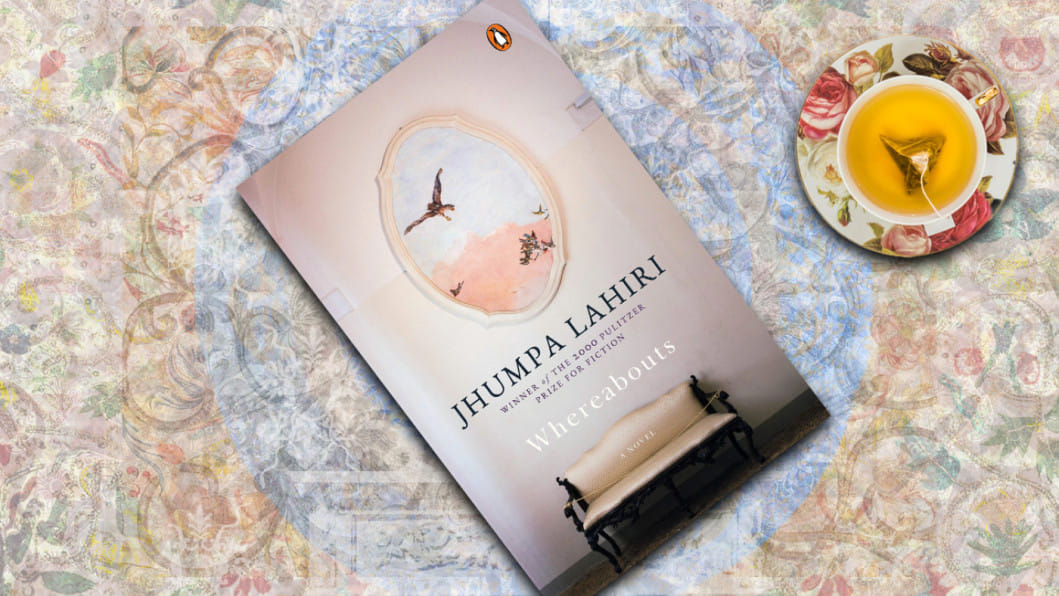

As I put down Jhumpa Lahiri's Whereabouts (Penguin India, 2021), I felt like I had been transported back to a school library, where more than a decade ago I sat staring at the back cover of Interpreter of Maladies (1999). I had no reference of the timely significance of the book or its author, no notion of what South Asian diaspora voices meant or why their visibility was important. I had simply been drawn to a section that I noticed no one would ever pick up a book from. The short stories were my introduction to South Asian immigrant and diaspora literature, and Lahiri's quiet and poignant insights, filtered through graceful prose, showed me a new world of storytelling. The impression this left stayed with me, as a reminder that the art of storytelling is diverse—there is no singular, correct way to write a good book.

Now, decades later, as I stare at the back cover of Whereabouts, I question myself as to whether I had forgotten this. I think I went in with loaded expectations of what a good novel, especially coming from Lahiri, would look like. And so when I stepped into Whereabouts, I lost my balance for a bit.

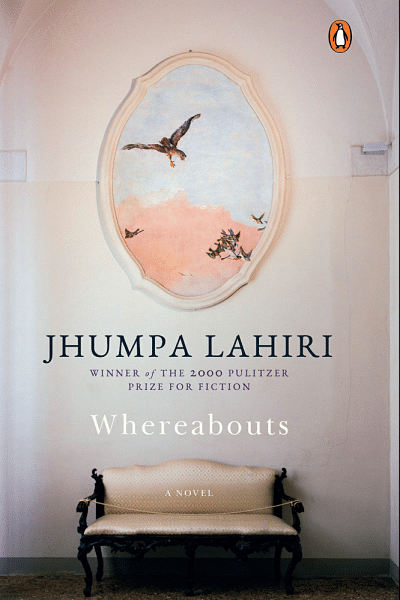

Whereabouts is Jhumpa Lahiri's third novel, published originally as Dove mi trovo (2018) in Italian and translated to English by the author herself, as she did with her work of nonfiction, In Other Words (2015). The book is an indication of her skill in navigating between languages without compromising the depth of her storytelling. In nearly all her previous work, such as The Namesake (2003) and The Lowland (2013), or the Pulitzer Prize-winning Maladies (1999), Lahiri took the reader into the cracks and faultlines of immigrant experiences brought to life with vivid settings and compelling characters; she left us there to absorb the conflicts and sense of loss, even if one has never been in an unhappy marriage, or been an immigrant. The heartache she wrote about was universal.

In Whereabouts, this universality is reflected in Lahiri's handling of space—fluid and ever-changing, a palimpsest of experiences, and instrumental to the story. While we are taken through her day to day experiences "At the Supermarket", "In the Country", "In My Head", and "At His Place", among other spaces, we notice that the character seems consistently at an emotional distance from her surroundings. This is reiterated with the recurring chapter heading of "In My Head", a space where the unnamed narrator most often dwells. It is at this site where the truths of her mind and body play out, rather than unfolding in her reality.

In the instances where the narrator does interact with others—a friend's young daughter, a woman sleeping beside her on the beach—there seems to be a visible contrast in how they are often more secure in the spaces they inhabit than the narrator herself. At times, the text seems like a dialogue between all these women in different stages of life.

Lahiri's prose here upends her generally agreed upon style of "showing rather than telling". Without any names or labels and suspended in a murky bubble of space-time, we find bits and pieces of a character page by page in this novel. The narrator eventually becomes a middle aged, unmarried university professor, living in an unnamed Italian city. Nearing the end, one is familiar with her innermost characteristics and histories. She is quick to judge people, sometimes harsh about the choices that people around her have made, yet she is compassionate in surprising moments. She lives with unresolved grief for her childhood. As you follow her through the liminal spaces she inhabits, she turns from the person you met on a busy street, to a friend you accompanied to watch a sunrise.

In a manner, the need for settings or worldbuilding facts are erased because of the universality of the microscopic activities of daily life: deep cleaning your home, ordering a sandwich while your train arrives, helping out a friend with their groceries, running into someone at the store, and an awkward visit to your family that turns out to be cathartic. As Lahiri sketches out these intimate motions of life, they become the backdrop on which our narrator deals with a complex texture of emotions: ebb and flows of grief, sharp jolts of pain, anger and regret, at times only a static hum of surrendering to the pulse of a community, the constant discomfort of belonging but never truly feeling one with the flow of life around you.

Such instances of emotion become more intense when the narrator displays sudden, unpredicted responses to the things around her. This stands out because throughout most of the text, a certain quiet or peace blankets her emotions, yet one feels the text as being constantly uncomfortable and dissatisfied. The moments of outburst occur when the narrator is no longer able to sit with that grief.

In the larger context of representation as performed in books, this body of work adds to the discourse about the reduction of South Asian or minority voices into singular aesthetics that allow only some voices to fit into what is deemed as respectable or desirable styles of telling diaspora stories. Jhumpa Lahiri's work in particular has raised debates around whether the publishing ecosystem ends up obscuring diversity in writing when they champion particular styles of authors deemed as trendsetters, such as Lahiri herself. But it's easier to grasp this discourse not as a debate but as a (fair) demand by writers that the world, especially the mechanical, consumer-driven ecosystems of publishing and writing, be more open to different aesthetics and be conscious of how it judges the respectability or desirability of books based on a very narrow status quo of "what good books should look like".

And what do good books look like? They are more likely to be the ones which reproduce respectability politics and play into the boxes assigned for "good immigrant" books. This happens, this is real; and it seems that Whereabouts is a reminder of how building singular styles and voices into concrete ways of creating performativity standards haunts even the ones whose styles have been used to build this framework.

It felt like the author herself, in writing this book (in Italian primarily), was navigating an exit out of the label of being the voice for a genre or an introduction to an entire community's lived experience, which is a burden that no one author should bear.

Ishrat Jahan is an early stage researcher who writes in her free time. You can follow her on Twitter @jahan1620.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments