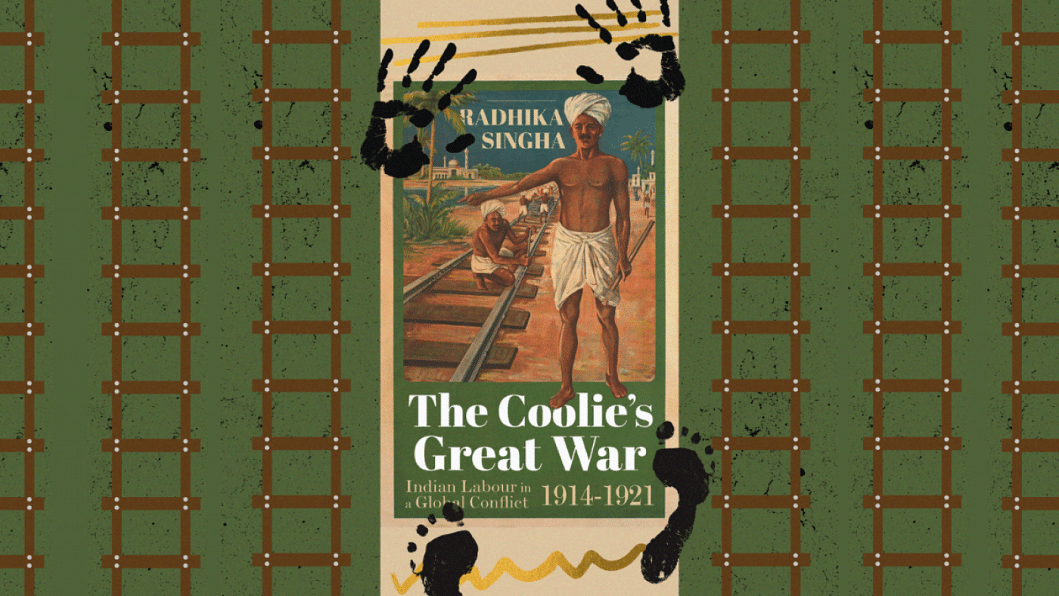

Radhika Singha's 'The Coolie's Great War': The forgotten ones of World War I

As of December 31, 1919, a total of 1.4 million Indians were recruited to various theatres of the First World War. Among them, approximately 563,369 were "followers or non-combatants". Even though they did not belong to the "martial classes" (soldiers, constables), the Indian government pushed them under the military rug so that it could boast of its military contributions in the War. As such, the non-combatant classes—more commonly referred to as "Coolies" or simply "menial followers"—became a subjugated figure; although, in the grand scheme of things, the British empire's military regime during the War had been built on these subjugated figures' backs. Radhika Singha explores this startling irony in The Coolie's Great War (HarperCollins India, 2020), and in doing so, brings forth an essential story from the chasm of obscurity, one that is primarily about the casteism that enables military power.

In one of the earlier chapters, we see a "low-caste" sweeper's body being refused by authorities for burial in the designated burial ground. One Reverend, Mr Chambers, chose to bury him in his Churchyard in Brockenhurst. "Surely Bigha Khan has died for England. I will bury him in the Churchyard", the man said. This event sets in motion the more common reality of casteism that the non-combatant followers had to grapple with even beyond the borders of their motherland.

"Caste norms tended to hem powerless communities into the hardest and most stigmatized sectors of work regimes", Singha writes. Those belonging to low-castes were assigned tasks like sweeping, latrine-cleaning, washing, and leather-crafting.

A chart chillingly portrays the heights of privilege that the Indian officers serving in the First World War enjoyed while their menial followers languished behind the scenes. For instance, by the end of the War, we see that the mortality rate of the officers against the followers in France was 176 and 2,218. In other frontier operations, it was 17 as opposed to 1,621.

Most of the labourers were recruited from the tribal areas (especially the Northeast, Bengal, Bihar, Orissa). Considered primitive and ignorant of the ways of the world, they were baited by incentives of getting a better chance at life, especially the jail recruits ("convict sweepers") who served as followers in the Indian Labor and Porter Corps in Iraq from 1916-1921. However, the reality of inequality, subjugation, and poor standards of life despite their backbreaking contributions soon disillusioned them. As such, desertion and gradual imprisonment became commonplace. Owing to starvation and exposure to harsh weather, many of the deserters even embraced death.

For the followers, especially the tribal recruits, homecoming also became a kind of blockade towards seaming into their regular lives. "The returnee could also materialize in very undesirable avatars", she writes, "in the form of the deserter, the prisoner of war… or one of the 'maimed' beings". The tribal recruits had to bear more brunt than the others because their return was anticipated with the possibility of them joining the insurgents along the Assam-Burma border or the Afridi insurgents around the North-West frontiers.

As for the disabled returnees, a man using crutches, for instance, was more likely to receive benefits than a man who had gone blind owing to injuries during the service. The former would be a more easily marketable image of the War's aftermath.

Furthermore, while the Viceroy Commissioned Officers (VCOs) were able to bask in rewards in line with a 'gentlemanly' status, "[t]he 'martial classes' would return to the ranks of the substantial peasantry, and followers to the stratum of the kamin, low-caste village artisans and labourers."

The Coolie's Great War is a tough read; not only because of its subject matter but also because of the extensive research and details pulsating through its pages. Bloated with archival accounts and evidence, the book does a commendable service in honouring the ones whose blood, sweat, and tears slid into the unknown. This working-class dimension to a popular story of war reiterates that the subjugation of certain kinds of labour and the pervasiveness of unfair hierarchy are deeply rooted in history.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor.

Radhika Singha's The Coolie's Great War (HarperCollins India, 2020) is available at Omni Books, Dhanmondi.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments