A rare triumph of US bipartisanship

After months of negotiations, the United States Senate recently passed a USD 1 trillion infrastructure bill. Passed by a vote of 69 to 30, it was an impressive display of bipartisanism at a time of deep polarisation. While there are still challenges ahead—in particular, disagreement over the USD 3.5 trillion budget blueprint that was subsequently passed by the House of Representatives along the party lines—the approval of the infrastructure bill offers a useful case study of what makes bipartisan deals possible.

The US has a long history of bipartisanship, from the Great Compromise of 1787 to Lyndon B Johnson's Great Society initiative in 1965 to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. As the late senator John McCain proved in 2017, when he defended the Affordable Care Act from efforts by his fellow Republicans to repeal it, even one or two defectors from a party can prove transformative.

But such defections are difficult to come by in a deeply two-party system in which the two sides at times seem like they live in a different reality (as is true of climate change or voter fraud). In such a context, crossing the party line can be perceived as a betrayal, threatening transgressors' position within the party and hurting their re-election chances.

A cornerstone of modern political science is that political actors behave rationally. Simply put, people will not initiate, join, or support any action that would undermine their own well-being. Given this, a policy can win bipartisan support only if it simultaneously advances the interests of both sides.

So what do America's two main parties want? Republicans tend to support unbridled competition, with the expectation that markets will naturally reward people in the ways they deserve and provide for people in the ways they need. Democrats argue that public intervention is crucial to correcting imbalances and protecting the disadvantaged.

Public infrastructure investment is thus a more natural cause for Democrats. But while Republicans might not like the idea of large-scale public investment generally—they prefer tax cuts to spending increases, and would prefer lower social spending—they do recognise that the private sector depends on public infrastructure, from roads and bridges to internet service. They might not like entitlements, but they do want the economy to run—and their constituents to keep voting for them. That means meeting certain basic needs.

This is one way that leaders achieve what the political scientist John AC Conybeare called "leadership surplus". After competing with other potential leaders for ascendancy, they "maximise their surplus or profit by providing collective goods against taxes, donations, or purchases promised in the election process".

Another way to accumulate a leadership surplus and pass broadly beneficial legislation is to find areas of common interest and show the other side how their priorities overlap. Moreover, leaders must sustain bipartisan buy-in while negotiating the details. For example, even if both sides see the need for modern, functioning physical infrastructure, progress can be stymied by disagreement on how to pay for it.

Republicans, at least when they are out of power, express concern about the growing budget deficit, which would ostensibly increase the tax burden on future generations. But this introduces an ideological constraint that has little merit: standard economic theory holds that future generations' welfare depends on the total national resources left to them, not on their resources minus their tax obligations.

Of course, Modern Monetary Theory would take this a step further, stating that a country like the US can accumulate virtually unlimited amounts of debt. Of course, this remains controversial—and certainly unconvincing to US Republicans. But the standard view is enough to demonstrate that investing in resources like infrastructure will bolster long-term welfare, regardless of the size of the public debt. It is the politician's job to make the case to ideological opponents in language that is most convincing to them.

There are also other means of securing bipartisan support for a policy or bill. Consider so-called pork barrel politics: the practice of slipping a localised project into a budget, in order to secure a particular legislator's vote. This is often considered to be an abuse of the political system, not least because such provisions might have little to do with the legislation to which they are attached.

But, while doling out pork can certainly be wasteful, it can also be a practical tool for enabling progress in delivering public goods. Rather than condemning the practice outright, we should ask whether the benefits of the main legislation are enough to justify the tacked-on provisions. One might describe this as political leadership on the ground.

In an ideal world, perhaps such provisions would not be needed. But there is nothing ideal about US politics, as years of congressional paralysis clearly demonstrates. The bipartisan vote for the infrastructure bill in the US, therefore, should be commended. One hopes it will serve as a reminder to both sides that, as contentious as the political climate gets, common ground can be a rewarding place.

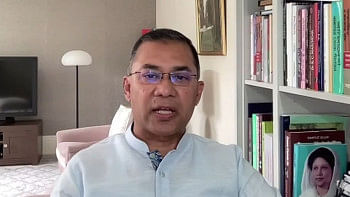

Koichi Hamada, Professor Emeritus at Yale University, was a special adviser to former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2021

www.project-syndicate.org

(Exclusive to The Daily Star)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments