The ‘P’ in Moral Policing Stands for Patriarchy

Being an English major, I had to read The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. It revolves around an extremist puritan society's obsession with shunning Hester Prynne for her "immoral acts". The moral policing in this novel later turns into a full-fledged witch hunt, as the puritan leaders dehumanise Hester and her child every step of the way.

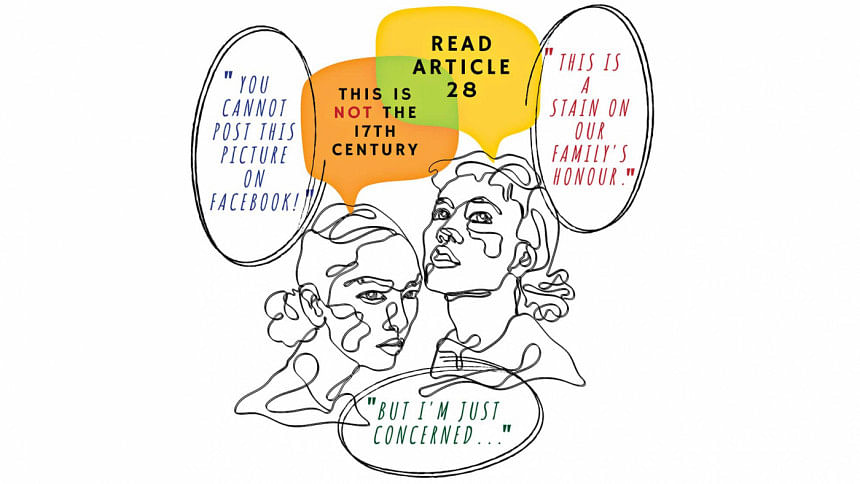

A novel set in 17th century colonial America couldn't have anything to do with 21st century Bangladeshi society, right? I thought so too, until I saw this pattern of patriarchal moral policing orchestrated repeatedly.

From the woman who was berated by random strangers for what she chose to wear, to a public figure who is being dragged through the mud for "immoral" personal choices she made — moral policing has become an extension of patriarchy in its attempt to forcefully fit every woman to the Madonna image.

Moral policing affects people of all genders, but women are more subjected to this euphemised form of harassment. The origin of this pattern is debated, but a moral high ground and subsequently the duty of being the moral guardian of women has been bestowed on men through everything from media to patriarchal social institutions. This notion of men being the morally superior protector of the morally vulnerable women who just so happen to carry the burden of "family or society's honour" is what legitimises extensive moral policing of women.

Is it legal? Absolutely not.

Constitutionally, moral policing compromises our civil rights and privacy rights as Bangladeshi citizens. In the case of women, Article 28 of our constitution promises women equal access to public spaces and institutions. Although moral policing itself is not a legal offence that can be tried, its impact on the person being policed violates our constitutional rights.

From overzealous relatives who try to regulate what women in the family post on social media to self-acclaimed moral protectors expressing "concern" or straight out harassing women in both online and offline spaces for their appearance or action, do so under the pretence of protecting the collective morality of our society. But as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie puts it, "If you criticise X in women but do not criticise X in men, you do not have a problem with X, you have a problem with women."

Everyone is allowed to have their subjective understanding of morality. However, to impose it as the objective standard in a way that compromises someone else's rights is questionable. And if that subjective notion happens to be rooted in misogyny or internalised patriarchy, it is simply unacceptable.

References

1. Digital Rights Monitor. (October 13, 2020). Moral policing on the internet is rooted in patriarchal ideals of controlling women's bodies.

2. Knopf Publishers. (March 7, 2017). Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions.

3. The Daily Star. (December 15, 2020). Moral Policing in Bangladesh: legal implications.

Tazreen is a part time English major and full-time feminist attempting to be the 21st century reincarnation of Judith Shakespeare. Reach her at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments