Time to address the growing wealth gap in Bangladesh

In a recent report, the World Bank stated that better targeted social protection programmes and reallocation of existing transfers to the poorest segment of society could reduce poverty from 36 percent to 12 percent in Bangladesh. The report, unveiled on September 16, 2021, found that the government's social safety net programmes were mostly focused on rural areas, even though almost one in five of the urban population is currently living in poverty. As a result, the World Bank report advised the government to rebalance geographic allocations between rural and urban areas.

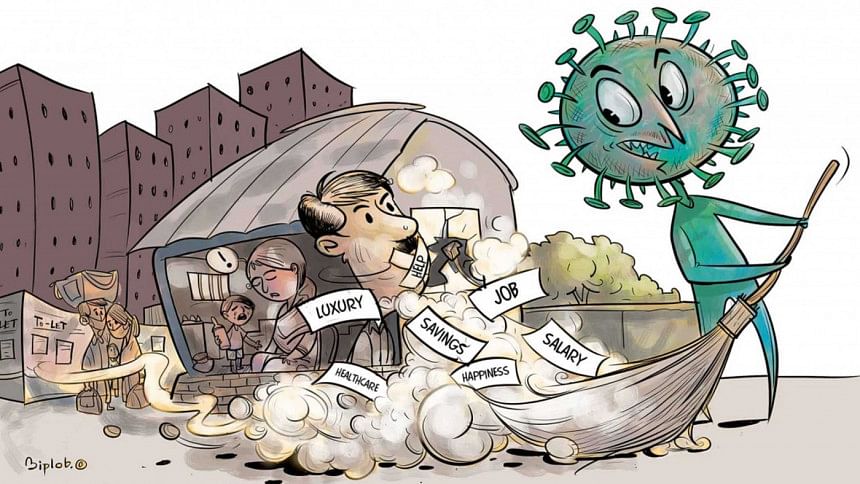

The pandemic-induced lockdowns and resultant economic slowdown over the past year and a half have undoubtedly pushed many people into poverty. According to several studies done by various organisations, the number of poor and extreme poor have risen significantly—although the figures vary. A survey done by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (Sanem) found that a person living below the poverty line in the rural areas would be spending less than Tk 2,260 to Tk 2,916, while in the urban areas, it ranged between Tk 2,516 and Tk 3,295, because of higher living costs.

The Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) conducted a study, which revealed that during the pandemic, over three percent of the labour force lost jobs, while 16.8 million people became newly poor. Around 69 percent of the employed population in urban areas have been put in the high-risk group by pandemic-related factors. Among them, the most affected groups were the labourers in urban areas who were engaged in construction, informal services, rickshaw-pulling, and launch- and boat-driving. Self-employed people like street vendors, hawkers, tea sellers, food stall owners and repairmen were also among the worst-hit. The urban informal sector lost about 1.08 million jobs, which was over eight percent of the total urban employment during FY 2016-17. Moreover, workers' wages declined by 43 percent in Dhaka and 33 percent in Chattogram.

The increase in unemployment forced people to reduce their expenditure on food, according to the findings of the Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) and the Brac Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD). The food expenditure of each urban household that was surveyed declined by 17 percent from the pre-Covid stage, when it was Tk 66 per day, while, surprisingly, the food expenditure in rural areas increased by Tk 1 to Tk 53. The decline could have long-term health implications for the urban poor.

The PPRC-BIGD survey also revealed that, for urban slum households, the significant increase in rent, utility, health, and transportation costs accounted for a 98 percent rise in the non-food burden for this group. Unable to cope with the crisis, 27.3 percent of urban slum dwellers had to migrate over the past year, and 9.8 percent of them had not yet returned.

While all these happened, the planning minister in May announced that the per capita income in the country had increased by nine percent—from USD 2,064 in FY 20 to USD 2,227 in the FY 21. This increase in per capita income at a time when a large number of people have fallen below the poverty threshold—because of the economic slowdown caused by the pandemic—suggests a growing gap between the rich and the poor.

The disparity between the rich and the poor has widened because of an unequal distribution of economic growth benefits, and because of a development model that has made Bangladesh one of the top countries for the quickest growth of ultra-wealthy individuals. According to data from the Bangladesh Bank, accounts with more than Tk 1 crore went up by 10,051, and deposits in such accounts rose to Tk 5,95,286 crore in 2020 from Tk 5,67,585 crore in 2019.

Even during the pandemic, we have seen big businesses getting substantial government support, while small businesses have continually struggled to get their share. Moreover, government aid programmes, which were intended to bring relief to the poor, have been repeatedly abused by people in power to further enrich themselves.

According to a Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) survey, the pandemic has not only exposed widespread corruption in the healthcare sector, but also created new opportunities for corruption in the country. For example, in the case of just one government relief programme, each affected family who were supposed to be the beneficiaries of the system had to pay an average bribe of Tk 220 to get a cash assistance of Tk 2,500. In addition, over 12 percent of the beneficiaries for government cash assistance were victims of irregularities and corruption, while 10 percent of Open Market Sales (OMS) card holders faced the same, according to the TIB findings.

Towards the beginning of this crisis, many government authorities claimed that the increase in the number of new poor was only "temporary." However, more than one year into the crisis, we see that a large number of people who went below the poverty line are yet to come out of it. Some top government officials have even gone on record to deny the poverty figures compiled by various independent organisations, while failing to collect or show their own data as evidence. This shows how little they care about the plight of the poor, as acknowledging it may prove the inadequacy of their own efforts and require them to take corrective action.

The government claims that it has spent more than three percent of the national budget as a percentage of GDP on social protection. However, if we focus only on poverty alleviation, that figure comes down to less than one percent. Therefore, in reality, pro-poor support from the government has not been sufficient to compensate for the losses incurred.

Returning to the World Bank's suggestion of rebalancing geographic allocations, we see that there is actually no need to rebalance between rural and urban areas. However, there has been a need to rebalance between the rich and the poor for a long time, but very few institutional steps have been taken to this end. It is here that government policy must change, and government rhetoric and action must match.

In the short run, it will require the government to increase its allocation for poverty alleviation and make social safety net programmes more impactful through better targeting (so that the most at-risk groups are prioritised), fast-tracking cash deployment and, equally importantly, by addressing corruption. Involving the local community could also make a huge difference. In line with that, the government should opt for a more bottom-up approach, instead of its usual top-down outlook. The government could also involve civil society members and NGOs in its relief programmes to reduce corruption in their delivery.

In the long run, development has to be more inclusive. And for that, there has to be some serious restructuring when it comes to the state and how it functions. Unfortunately, given our deeply politicised structure of governance, with its poor accountability mechanisms, that could be a huge challenge. Overcoming this will require a massive pushback from the citizens demanding greater accountability and greater reforms in how anti-poverty policies are made and pursued.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

His Twitter handle is: @EreshOmarJamal

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments