Remembering a literary personality: Farida Majid (1942-2021)

I find two distinct types among denizens of the world of letters. There are writers single-mindedly focused on literary production in one genre or more, and others I would call, for want of a better term, literary personalities. The literary personalities may write too, but with a certain offhandedness, as if they didn't want to channel all their creative energy into writing. They also want to experience 'the literary life' in all its varied aspects. They love to hang out with other writers, edit little magazines, run small presses, go to literary jamborees.

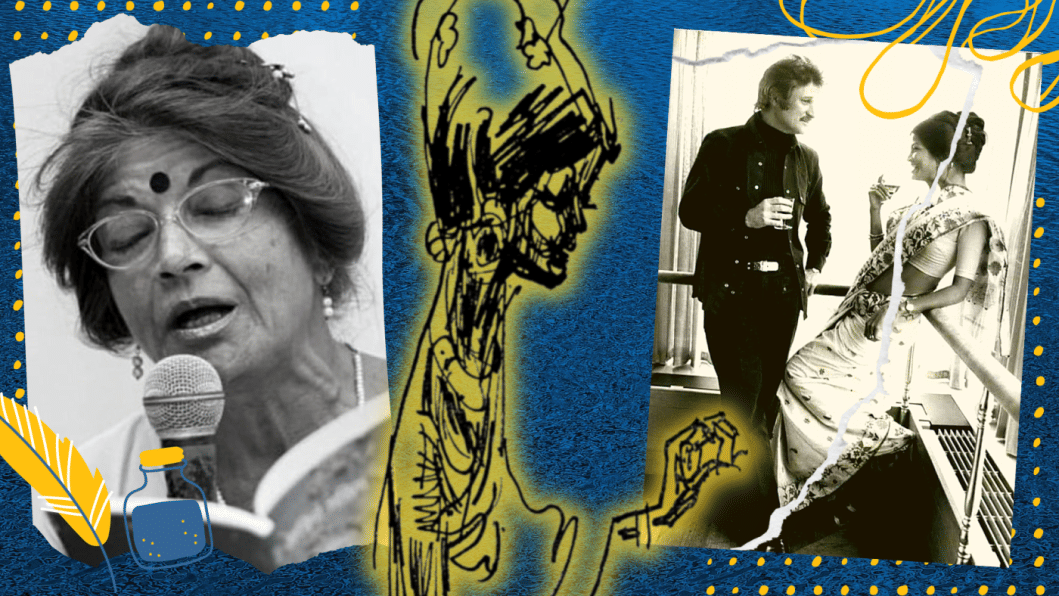

There are two subtypes of the literary personality: the bohemian and the academic and/or bureaucratic. Exemplifying the bohemian sub-type to perfection were Rajat Neogy, poet and founder-editor of Transition magazine, and Meary Tambimuttu, poet, book publisher, and founder-editor of Poetry London. Farida Majid belonged in their company. In fact, her London friends dubbed her "the Female Tambimuttu."

Farida's personality left a vivid and lasting impression on those who got to know her. In 1993, Alastair Niven, himself an eminent academic/bureaucratic literary personality, invited me to join his jury panel for the Commonwealth Writers Prize, along with Dr Shyamala Narayan, an Indian academic. Alastair and I were chatting over coffee, when he suddenly lowered his voice and asked if I could enlighten him on something that had been puzzling him.

He had been struck by the existence of two polar opposites among South Asian women. Dr Narayan represented one end, demure, soft-spoken, quietly efficient. And the opposite? "Do you know Farida Majid?" Alastair asked. It was well over a decade since he saw her last, but time hadn't diminished the impression she had made; she was glamorous, vivacious, outspoken, unconventional.

I knew Farida by reputation before I met her in 1977, when her career as a London literary personality was at its peak. Poetry was her passion, and she spent most of her time with poets. They gathered to read out and talk poetry every Thursday evening in her Chelsea flat. She had launched The Salamander Imprint with a 24-page pamphlet, Take Me Home, Rickshaw (1974), containing her translations of leading Bangladeshi poets, from Shamsur Rahman, an intimate friend, to his younger contemporaries. The proceeds from sales went to a school in Dhaka. The cover was designed by the famous Polish-born artist Feliks Topolski, whose friendship with Farida and her poetry circle deserves celebratory mention.

While the poets talked, Topolski sat doing portraits. The Thursday Evening Anthology (1977), edited by Farida, contained poems by 18 poets, with a facing portrait, and a line or two of comment at the bottom. The most memorable—"Farida's is the last salon"—came from George MacBeth (1932-92). Others in the anthology include Gavin Ewart, Fleur Adcock, Andrew Waterman, John Welch, and James Sutherland-Smith. Ted Hughes, though one of Farida's close friends, didn't come to the evenings, perhaps because he lived far from London.

Farida published a number of outstanding individual poetry collections: The Horses of Falaise (1975) by Victor West; in 1976, Jack Carey's Woods and Mirrors, and Jim Burns's The Goldfish Speaks from Beyond the Grave, which got a Poetry Book Society recommendation, as did Kit Wright's The Bear Looked over the Mountain (1977).

Farida had been on the jury for the 1977 Commonwealth Poetry Prize, which went to Arun Kolatkar's "Jejuri" (1976), now regarded as a classic. But her sparkling career as impresario, writer, and literary arbiter would suddenly fall apart. The Home Office wanted to deport her for being in breach of laws pertaining to foreigners living in the UK. Eminent literary figures spoke up for her, to no avail. Being an American citizen she moved to New York, where she taught at Columbia and CUNY until her return to Bangladesh in 2005.

I met her in New York in 2000; she spoke at length about her London years, and gave me two of the books she had published, as well as two touchingly resonant new poems that I published in Six Seasons Review: "Garbage Truck Blues," and "An Insomniac's Prayer". I included "Inversion of a Convert", from The Thursday Evening Anthology, in Padma Meghna Jamuna: Modern Poetry from Bangladesh (SAARC Foundation, 2009). It's a brilliant riposte to the Aruneyi Upanishad.

I called on Farida a couple of times, and would run into her at literary festivals, but most of our communication was telephonic. She published a Bangla poetry collection, and translated a number of poems by Bangladeshi poets, Sanjeeb Purohit among them. They made up an admiring circle, giving her the literary companionship she needed. She was also working on a Quranic commentary. Someone should sift through her papers and see what can be published. The last time we talked it was clear doctors had diagnosed cancer and that she was in denial. I am told that though physically shrunken, her spirit remained unshaken till the end.

Farida is in two iconic photographs on the internet, with Allen Ginsberg, and with John Ashbery. She was young, animated, exuding seductive charm. That is how I wish to remember her.

Kaiser Haq is a poet, translator, essayist, critic, and academic. He is currently Professor of English at the University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh (ULAB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments