All screen and no play?

We are all familiar with the sight by now: everyone in a family—adults, children, parents—sitting together, but each concentrating on their personal device, usually a smartphone or a tablet. So familiar are we that we have also accepted it as our reality. Those of us who cannot stand the awkwardness of certain social settings are even grateful to have something else to look at, which makes us appear as if we are otherwise busy or occupied. However, when it comes to children's usage of these devices, there is no denying the fact that such daily and prolonged exposure to screens is indeed concerning as it may have long-term harmful effects on them.

With the increased ease of access to high-speed internet and compact devices, children over the last decade or so have been introduced to screens pretty much since infancy. It has been, in a way, fascinating to see how quickly some babies can get the hang of working smart devices without any help. Busy parents even find solace in the fact that at least their child is sitting in one place, occupied with one thing, instead of running around or getting hurt while they—the parents—work outside or around the house.

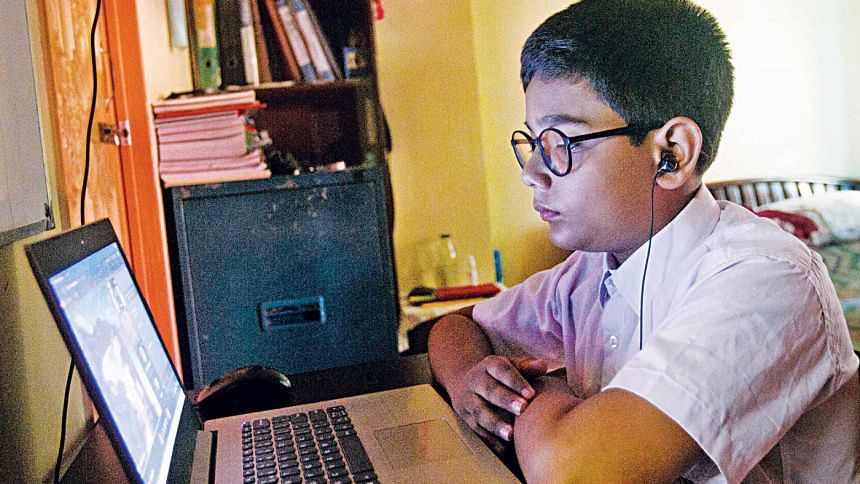

But smart devices are untrustworthy babysitters. While the child is occupied with one thing (and in one place) for hours, that one thing is a screen which not only affects their health—physical and mental—but also eliminates their desire to do anything else that is productive. And in no other time have the effects of this been clearer than during the last one year and a half of the Covid-19 pandemic and of online schooling.

A recently published research article, titled "Prevalence and impact of the use of electronic gadgets on the health of children in secondary schools in Bangladesh: A cross sectional study," reveals how much dependent students have become on technology. The study was conducted on 1,803 secondary school students (Classes 6 to 10) from English and Bangla medium schools as well as madrasas, between June and December in 2020.

One may assume that it is because of online classes that children are spending more time in front of screens. However, for the year 2020, only about 25 percent of survey participants—of more than 87 percent who reported using any form of electronic gadgets—used those for attending online classes. According to the report, most of the students (around 39 percent) used smartphones and other devices for watching cartoons or movies, followed by almost 30 percent using them for other reasons.

Regardless, one thing that was evident from the study was that students' engagement with screens increased during the Covid-19 pandemic. While 33.5 percent of the students reported using gadgets for over two hours daily in 2019, this proportion surged to almost 53 percent in 2020. The overall percentage of respondents using these gadgets, for at least five hours a day, was also three times more last year than it was in 2019. And while around 28 percent said they spent less than two hours daily engaging in outdoor activities, nearly 27 percent said they did not spend any time outdoors at all, or spent so little time there that it would not be worth considering.

So, what does such an increment in children's usage of electronic devices indicate?

With in-person classes remaining closed for 543 days since March 2020—and reopening in phases just a month ago—children had to bear the shock of their daily routine being drastically changed. Not only were they now pursuing one of the most important aspects of their lives—their education—through screens, but they were also deprived of all the positives of going to school, such as having a circle of peers and being able to socialise with them through conversation and shared activities.

In our cities, where playgrounds are becoming scarcer by the year, school is often the only place where many children get the chance to play outdoors, be physically active, and thus avoid dependence on screens. It is, therefore, not shocking that the study also found an increasing pattern of gadget use going up from children living in rural areas, to those in suburban areas, to those in urban areas. So, whereas a little over 90 percent of urban respondents said they used one or another form of gadget, the percentage was a bit lower, at about 84 percent, for rural participants. Higher technological dependence was also found in students who came from more financially solvent families.

Regardless of their geographical location and financial standing, the most concerning findings of the study remain true across the board: the harmful physical and mental effects of children's technological dependence. For instance, respondents who spent more than six hours with gadgets daily were found to be more than twice as likely to experience regular headaches, than those who spent an hour or less doing the same. Moreover, more than half of those who used gadgets for more than two hours also reported feelings of depression and sleep disturbances.

In contrast, participants who reported less than an hour of daily usage of gadgets reported significantly fewer instances of headaches, back pain, depression, sleep disturbance, and visual disturbance. Pain in limbs was the problem most experienced by this group, but that too in only about a quarter of them. This is in stark opposition to the nearly 50 percent, on average, of participants who reported using electronic devices for more than two hours daily, who were also suffering from different forms of the aforementioned physical and mental ailments.

Now, the simplest solution to the increased dependence on screens would be to lower and limit the time children spend glued to these devices. But before parents snatch away their children's laptops, smartphones and/or tablets, it may be fruitful to take a minute to visualise the child's perspective, too.

While children are beginning to return to in-person schooling, students from grades besides fifth and those who are SSC candidates (for 2021 and 2022) are only attending classes for a couple days a week at most. Schools that have the infrastructure to do so are still heavily dependent on online schooling. So it will be a while before children can stop looking at their screens to continue their education. And as long as they are trapped at home—especially for those in urban areas—their only solace may be in these electronic gadgets, which they can use to stay connected to and updated about the outside world.

Instead of imposing blanket restrictions on their screen time, it may be more useful for parents and guardians to first discuss with children why spending excessive amounts of time on electronic gadgets is unhealthy for their mental and physical well-being. The limitations can then be applied in phases, thus letting them eventually get used to using their devices for online classes and then for a specified period of leisure every day. Not only will this help build trust between the caretaker and the child, it may also inspire children to self-monitor and regulate the time they spend with screens. But parental supervision is key to any desirable change.

That said, the problem of online-offline class arrangements and the lack of outdoor spaces for children, which in part is responsible for their increased dependence on screens, are something that parents can't solve. It will require interventions from the higher authorities.

Afia Jahin is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments