From Shahaduz Zaman’s docufiction Ekjon Komlalebu

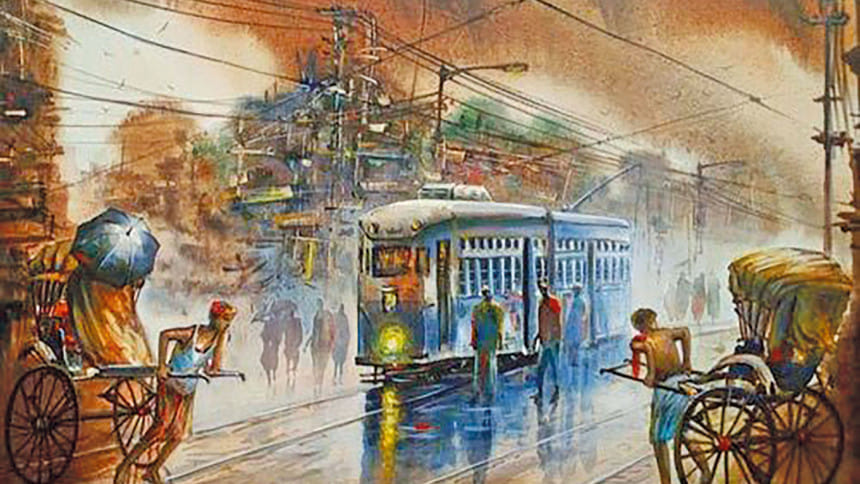

Like a reptile emerging from the dust of centuries, Kolkata's Ballygunge Down tram is snaking its way towards Rashbihari Avenue. Ghon! ghon! chimes its bell, ringing out in the last of the fading afternoon sun. Sitting at the counter of Jolkhabar stand, Chunilal has noticed something. A figure, male, walking in the direction of the oncoming vehicle. The man moves fast, so does the tram. The driver clangs the bell urgently, shouting out, but the man persists up onto its path, regardless. And he disappears under the catcher, the breaks screaming to a halt. Chunilal rushes to the scene and drags the man up and out from his confinement. A crowd has gathered by now. "What is your name?" they ask. "Where are you from?" Not one of them is aware that this man, this very man, once penned the following lines:

From footpath to footpath in Calcutta—footpath to footpath—

Like primeval serpentine sisters tram lines are spread out

Under my footsteps; I walk on, feeling their poisonous vapid

Touch in the blood coursing through my veins.

It is drizzling—the wind is somewhat chilly;

I remember some faraway grassy green land rivers and fireflies—

Where are they now?

Have they lost their way?

Lying in a pool of blood, the man mutters- "My name is Jibanananda Das. I live on Lansdowne Road, house number 183." Having said this much he tries to stand, but falters and crumples onto the road. The crowd lifts him and takes him by taxi to Shambhunath Pundit Hospital. The doctors there examine him—he has a fractured right leg, and some broken ribs. They bandage the leg and the ribs; they administer saline; they give him oxygen through the nose; they prick him with various injections. Unconscious, on a faded iron bed in the emergency ward, lies Jibanananda Das—the great enigma of Bengali writing. The whirpool of life has plucked the poet from Barisal, a land of green grass, rivers and butterflies and thrown him down on the toxic tramline of Kolkata.

***

Poetry, wisdom, fable; pastures, birds, flowers—from infancy to adolescence, Jibanananda was enveloped by the enchantment of nature. It was as though the world was his playground, studded with truth and beauty. No doubt his childhood was also filled with compassion— was it this combination, weaved into his soul from birth, that nurtured the seed of danger in his life? When the world slowly revealed itself to him, in ugliness as well as beauty, to what effect would that cocoon shatter?

Years ago, Kusumkumari had nursed her son back to life in that northern air, and from then on Jibanananda had trailed her like a duckling. Throughout childhood he heard her lines- "When within our country will that boy be born/ Who not by words but by deeds grows big and strong?" The desire, his mother's own, set the young boy a challenge. To be a man of action, however, would be a tall order—he was a reticent character, not the type who could speak freely. His whole life was spent as an introvert, wrapped up within himself

Jibanananda observed how Kusumkumari prioritised her poetic endeavours above all else. And steadily, he also learnt the art of writing. Towards the end of his days, he resided alone in one room at 183 Lansdowne Road, while his family members occupied another. After his demise, when the space was examined, certain things came to be discovered. There was a table and chair upon which lay some exercise books, a few red and blue pencils, one pot of ulekha Kalir Dowat ink and a fountain pen. In one corner of the room sat a stool, upon which were assembled some neatly stacked newspapers and a variety of literary journals. There was a rolled-up mat propped against the wall. And in the same area a taktapos topped with a thin mattress, sheets and pillows, a coverless quilt and a hand fan, beneath which lay some black, tin trunks. It was the trunks that before the significance, for in them lay an astounding discovery- the wealth of Jibanananda's labour in unpublished stories and scores of manuscripts. One was reminded of the treasure that poured from Tutankhamun's pyramid.

It was Jibanananda's sister Sucharita Das and the poetry loving student Bhumendra Gupta, who assumed responsibility of the trunks. The collection was moved from one relative's house to another— sometimes it would find itself in a storeroom. At other times a loft somewhere. On one occasion, a disaster occurred— the entire collection was lost while being transported by tram from one residence to another. It was later recovered, with great difficulty, from the depot. After various such trials and tribulations, the papers eventually came to reside in Kolkata's archives. Writing about these unpublished manuscripts, the writer Sandeepan Chattopadyay said the following: "In just fifty years the papers yellowed. But despite the fact that no deterrent other than naphthalene was used, no insects had the audacity to go near Jibanananda's work."

It was Bhumendra Guha upon whom, after quite some time, the responsibility of deciphering the works fell. From time to time he associated with Sucharita Das, and Jibanananda's brother Asokananda. Later, he was in contact with Debesh Ray, Sankha Ray and Afsar Ahmed. Bhumendra went on to become a renowned Doctor, but the end of his life was dedicated mainly to studying Jibanananda's manuscripts, which he would sit avidly pouring over with a magnifying glass.

***

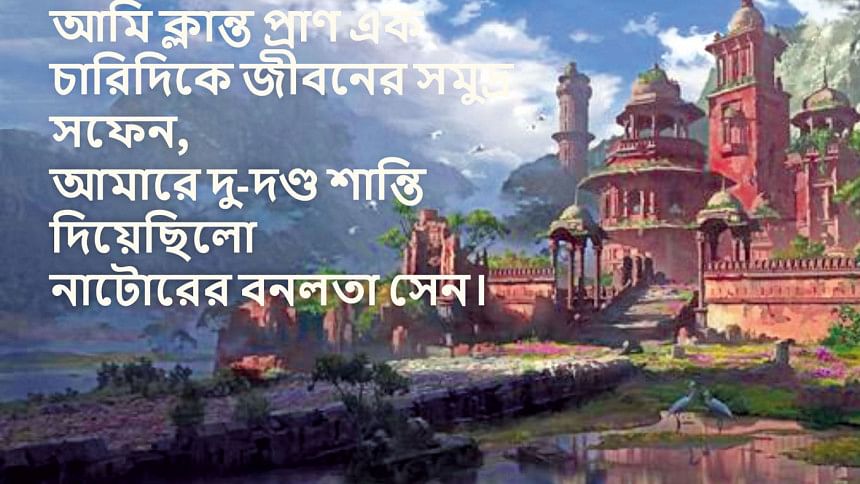

Jibanananda had long understood that an artist was an unlawful, unnatural person, who would always lead a solitary, lonely life. While the literary dignitaries continued to ignore him, he remained undeterred, focusing his worries and thoughts only on his work. Adhering to Gautama Buddha's words, "You yourself must strive, and be your own light," Jibanananda decided to write for his own sake. And in this arduous journey, his only companion was Buddhadeva Bose. His work on prose and novels remained a secret, and his focus turned to poetry. He began to work in earnest, editing each of his poems countless times. Just as a sculptor takes a single stone and trims the excess parts to unearth a hidden form from deep inside, so too Jibanananda dug up words to bring out a poem. His drafts clearly showed his meticulous efforts. It was at this time that after several revisions, Jibanananda created his most celebrated poem, Banalata Sen:

For a thousand years I have walked the ways of the world,

From Sinhala's Sea to Malaya's in night's darkness,

Far did I roam. In Vimbisar and Ashok's ash-grey world

Was I present; Farther off, in distance Vidarba city's darkness,

I, a tired soul, around me, life's turbulent, foaming ocean,

Finally found some bliss with Natore's Banalata Sen.

Her hair was full of the darkness of a distant Vidisha night,

Her face was filigreed with Sravasti's artwork. As in a far-off sea,

The ship-wrecked mariner, lonely, and no relief in sight,

Sees in a cinnamon isle signs of a lush grass-green valley,

Did I see her in darkness; said she, "Where had you been?"

Raising her eyes, so bird's nest-like, Natore's Banalata Sen.

At the end of the day, with the soft sound of dew,

Night falls; the kite wipes the sun's smells from its wings;

The world's colours fade; fireflies light up the world anew;

Time to wrap up work and get set for the telling of tales;

All birds home—rivers too—life's mart close again;

What remains is darkness and facing me—Banalata Sen!

***

After the publication of this poem, Sajanikanta wrote in Sanibarer Cithi: "One of the strategies of these talented poets is to needlessly mention the name of some gentleman's daughter, and make us curious. While writing 'Economics,' Srijukto Buddhadeva Bose unecessarily brings up 'Queen.' In 'Jatok,' A. Sri Joutirindra Maitro greatly embarrasses a woman called 'Surma,' and A. Sri Samar has done with the 'soft, tender body' of some woman named Malati Ray, something he shouldn't have attempted in the first place. This notorious trend was started by none other than Natore's 'Banalata Sen'…"

***

The identity of Banalata Sen has always been a topic for speculation. The mystery, however, has never been resolved. Jibanananda once said to Ashok Mitra that he came to know in a newspaper, about a state prisoner named Banalata Sen, held in Rajshahi prison. Akbar Ali Khan meanwhile, wrote that while he was serving as a government bureaucrat at Natore in Rajshahi, sifting through some old documents from the British era, he discovered that Natore was once a popular hub for sex workers. Akbar Ali Khan believed that Banalata Sen was actually a prostitute. He opined that there was a connection between Buddha's 'eternal journey' and the line "For a thousand years I have walked," and that both voyages infer elements of going astray, and sin. Two characters mentioned in the poem, Bimbisara, the King of Magadha, and Ashoka, the Emperor of Maurya, were both followers of Buddhism. However, the lives of each were tainted by wrongdoing. Ashoka had been responsible for causing widespread massacre, while Bimbisara was killed by his own son. The poem also cites a place called Vidarbha, which according to the Mahabharata, was the paternal home of a stunningly beautiful woman named Damayanti. The Mahabharat narrates how the demigod Kali disrupted Damayanti's conjugal life, and that this is why Vidarbha is beset with memories of sin. Banalata Sen refers to the name of a further city, called Vidisha. Vidisha (formerly known as Bhelsa), finds mention in Kalidasa's Meghaduta where it is portrayed as the prime centre of crime and sin. A third city named in the poem is Shravasti, where Buddha spent twenty-five years of his life, and was approached by a number of lustful women trying to break his meditation. In Akbar Ali's view, the onset of the poem portrayed a world filled with lust and sin. He raised a question: shouldn't Natore be considered one such place in the context of the time? And the stunning Banalata Sen a devious prostitute? Besides, the poet meets Banalata only in the darkness of the night, creating further suspicion. At one point of the text, he asks the woman, "Where have you been for so long?" This denotes various potential meanings. It might be that he had met this woman earlier in his life, but that they had later lost touch. Or that the woman thought that if she had met this learned man before, her life might have taken a different turn.

There have been many conjectures on the identity of Banalata Sen, but Akbar Ali Khan's assessment is very different from most.

***

Jibanananda's life had been greatly influenced by three women. First, was Kusumkumari. Though mother and son had grown apart over the years, she had been his first refuge, the prime inspiration for his poems. Then there was Labanya, with whom he'd never shared an emotional closeness. Lastly was Shovona, who had been intimate with Jibanananda for a short while, but who had travelled far from his world. Despite this, Jibanananda had always carried his love for her in his heart. Even in 1948, twenty long years after their liaison, when he was crushed by the blows and counterblows of life, he still yearned for Shovona. He composed verse after verse to remember her, and her presence can be strongly felt in one of his stories written during this period: "At Midnight from Humayun Place."

"At Midnight from Humayun Place", is set in Kolkata. It tells the story of a man named Shomnath who exits Humayun Place late at night, and stands on Chowringhee. He can't remember where he has been or what he has been doing until now. The last tram has left, and he eventually finds a bus to go home. Shomnath lives alone in a small, second storey room. The people on the ground floor have already shut the main door. He can see the light on in his room, yet can clearly remember turning this off on his way out. He can't understand it at all. Seeing that he has no other option, he climbs up the drain pipe to get to the second floor. Yes, the light is indeed on. He tries to find out if anything is stolen. No, everything is there. There is nothing costly in his room anyway, only a few books. Satisfied, he turns off the light about to go to bed, when suddenly he hears a woman's voice. Shomnath lets out a shout in fear: "who is this?!"

"It's me," the woman says. "Don't turn the light on." Shomnath can recognise the voice now; this is the woman he once loved deeply.

"You, here?" he asks, astonished.

No, there is no one else in the room right now, only the voice. He continues the conversation: "Twelve years have passed… Where have you been all this time?"

Voice: "I have been to so many places. As many as I could go to."

Shomnath: "I heard that you were in Paris—"

Voice: "Oh, you did as well."

Shomnath: "When did you go?"

Voice: "During the bombing."

Shomnath: "Paris was a free city. Then the Germans took it…"

Shomnath and the woman continue to converse in the dark. They talk about how she, his former lover, married a rich Muslim businessman, and how the couple became stuck in Europe during the Second World War. They discuss whether they themselves could have married or not, in an earlier life. Then, before dawn, the woman takes her leave and Shomnath entertains himself with a bottle of wine.

This story, in which the protagonist discusses love, war and politics with a bodiless voice, is an unusual one. Did it perhaps represent a desire to incorporate Shovona, if not in the flesh, then as a verbal presence?

Jibanananda had long ago accepted the truth that Shovona had departed his life for good. However, it was a fact that also broke his heart:

When you leave—

The way flamingo leave—fly away—heading for far-off Malabar hills

Not looking back at dark shores of the past—don't they have doubts or feel pain?

I know though you will never return, life's first experience of a harvest;

What await now are twilight, winter and biting drops of dew!

The article is a collection of excerpts from Shahaduz Zaman's Ekjon Komlalebu. The translators are Marzia Rahman, a writer and translator based in Dhaka, and Amy Parsons, a teacher and translator at the Language Centre, SOAS University of London.

The poems of Jibanananda Das used in this writing are translated by Fakrul Alam, UGC Professor, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments