Battle Ground Baliadanga- A milestone in our liberation war

September 20, 1971, is an unforgettable day in the liberation war of Bangladesh. On this day, 17 freedom fighters laid down their lives in the sodden battleground at Baliadanga, Satkhira. During the battle, only 62 brave soldiers of the Muktibahini, imbued with patriotism, armed with old and outdated small firearms, fought against 1,200 Pakistani soldiers armed to the teeth with long-range artillery, guns and the most modern automatic weapons.

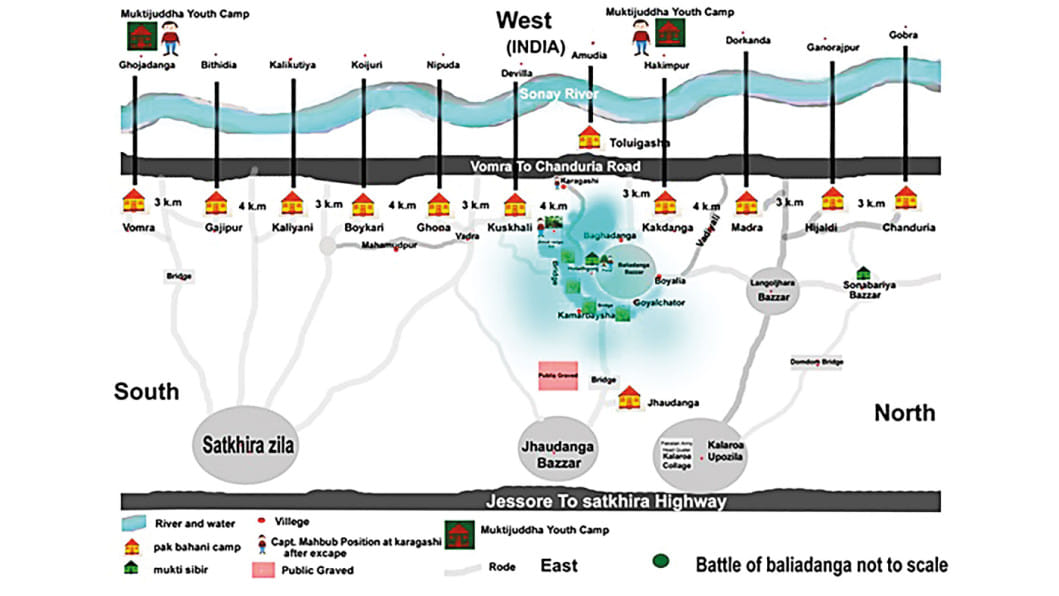

Baliadanga is a rural village near the border between Bangladesh and India in our southwestern territory. During the Liberation War, this was a part of sector 8 consisting of the greater districts of Kushtia, Jashore, Khulna, Barisal and part of Faridpur. The great divide of the river Padma separated it from the other territories of our country. In this region, many big battles were fought between the Muktibahini and the Pakistani army. One such battle took place at the village Balidanga, having other villages such as Hothatganj, Boalia, Goalchatar, Bhadiali, Baghadanga, Kamar Baisha and Kakdanga around it. The Indian Border Security Force (BSF) had its station at Toluigachi and Koijuri beside the villages Hakimpur, Mandra, Dorkanda etc., of West Bengal. Initially, a quick operation was planned as a predawn attack on the Kakdanga BOP occupied by the Pakistan army. This was ordered by Major Manzoor, newly appointed sector commander of Sector 8.

As per his order, I had sent a small contingent of 25 men from my Alpha Company. Almost all of them had returned from an Indian training camp at Chakulia, having received six-week training on hit and run guerrilla tactics. They were equipped with grenades and light arms for close-quarter combat. The objective was to make a surprise incursion to kill the guards inside the BOP and occupy it. Major Manzoor also planned to send another two Muktibahini platoons behind the enemy lines. Once our planned attack on the BOP was successful, the second contingent would move quickly in aid and occupy it by destroying the enemy's ability to recoup. This second contingent was led by Captain Shafiq Ullah, commander Echo Company of Sector 8. Having finalised this plan, Captain Shafiq Ullah's platoons were stealthily settled at Baliadanga, East of Kakdanga. They entrenched themselves on the high banks around a large pond surrounded by many trees, including one very tall tangerine tree in the corner.

This operation was carried out under the top supervision of the Eastern Command of the Indian Army from Fort William, Kolkata. The General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) General Jagjit Singh Aurora was in the operation loop.

As a newcomer, this operation was deemed an acid test for Sector Commander Manzoor and the Muktibahini. To misguide and mislead the Pakistan army about our attack on Kakdanga, the Indian Army command also asked Manzoor to mobilise the troops under sub-sector Boira and Mandra under the command of Captain Khandakar Nazmul Huda and Captain A.R. Azam Chowdhury, respectively. The reason was simple. The reorganisation of Bangladeshi forces after the initial resistance was already in its final stage. This was reinforced by the six-week condensed training of our highly enthusiastic Muktibahini in various camps across India. It already hardened our staunch to get back to our own land from which we were forced out. Indian army in the Eastern command had been mobilised in the frontier to a great extent waiting for political leadership to give a green signal to force Pakistan out of Bangladesh territory.

During the deployment, several operational meetings were held on general, tactical and strategic issues between the Indian Eastern command and Sector Commander Manzoor to plan and devise a winning battle. In a nutshell, the operation was given a high degree of importance. Perhaps this was a rehearsal for the potential final assault to liberate Bangladesh. These tactical and operational issues were less circulated for reasons of security and surprise.

Nasir and Sattar led my small contingent; they were my trench buddies ever since my arrival at Gojadanga, opposite Bhomra BOP at Satkhira border. I arrived there in the last week of April. Both Nasir and Sattar hailed from Satkhira and had participated in several operations against Pakistani hordes during their initial combing operations following the crackdown on March 25. So, they had the courage and experience to face the enemy.

On September 16, 1971, the team led by Nasir and Satter attacked the Pakistani position Kakdanga. They managed to reach the ground objective area and captured trenches and positions within the extended area of the BOP. But they failed to capture the BOP. There was continuous fire and counter fire, and it continued for two days.

Major Manzoor perhaps thought of having a stand-by replacement during the cross-firing, so he called me from my company to Hakimpur on September 17. Shafiq's supply of ammo and food (both dry and soft) had already been depleted. He was virtually running the troops unfed or underfed. Some local villagers, who dared to move with food through the Pakistani positions in disguise while risking their lives, were the only means of survival for him and his soldiers.

For Captain Shafiq Ullah, the main concern was to remain calm. In the afternoon of the 18th, he was wounded by a splinter during firing and counter firing. Due to heavy blood loss, he became unconscious. When the information reached the sector commander, he ordered his immediate evacuation with me as a replacement. His premonition to keep one officer stand-by proved timely, as I had already moved from Gojadanga, Satkhira in the morning. He had mobilised a small group of 17 men, including a young guide hardly 13 years of age named 'Guerrilla Momen', to help me reach the location.

Shafiq Ullah was my mentee. When he served as a Professor of Jhenidah Cadet College, I recruited him to join the struggle. Later on, I introduced him to Major Abu Osman Chowdhury, the chief of the Muktibahini at Chuadanga. Major Osman was the East Pakistan Rifles (EPR) Four wing commander and organised resistance at Kushtia, aided by the Awami League-led Sangram committee supported by the rebellious EPR wing. I was a part of this battle and organised the people of Jhenaidah for resisting the Pakistan army crackdown. I was very fond of Shafiq Ullah since he was brave and fully committed. I was anxious, knowing that he was wounded and unconscious. After preparing with food and ammo, I started for the tangerine tree on the midnight of September 18, with 17 men, including Shahadat, Baker, Latif, Shahin and Momen. The terrain was wet with heavy rain. In the darkness, we continued walking and reached near the site at dawn. Shafiq Ullah had meanwhile regained consciousness and finally left for Hakimpur. On the last leg, he reached Barrackpore Indian military hospital for treatment. After a hearty send-off, I took over the command of the band of 62 soldiers, mostly youth, students, ordinary cultivators and labour under the supervision of several EPR non-commissioned officers.

Behind the scenes, higher-level activities had little or no perception to our foot soldiers or us. However, no operation was too dangerous as every soldier was ready for supreme sacrifice. Our prayers, vigil, gun barrels and smell of gunpowder were all aimed at killing the enemy. At times, both sides appeared tired of throwing bullets. In long monotony, the only respite was the intermittent bombardment. Between the cracking sound of wireless sets, we cried out for fire, seeing any movement on the enemy side. Our boys tried to hide untiringly in the trenches for hours without rest. The call of nature, occasional movement for ablution and other regular chores, and endless monotonous waiting, with or without some sleep, made it challenging to keep our location hidden.

September 19 came to an end, and the nightfall gave us the cover of darkness. All firing stopped. We enhanced our position with additional sentry posts. I found, however, a lot of movement of transport with burning headlights in the Water & Power Development Authority (WAPDA) office area during the night. Early dawn, a cultivator came swimming through the flooded lake to report heavy movement and mobilisation in the WAPDA office area. There were many truckloads of soldiers travelling along the Hothatganj, Kushkhali, Bhadra, Mahmudpur roads. This man, named Suleman, introduced himself as a supporter of Mahbub Sarder, a leader of local Jamat-e-Islam. He was surprised by the resilience of 'Mukti Fouz' against Pakistanis and opted to help us. He was a member of the local Muslim League. Earlier, I sent out a scout Shahadat to take a closer look to assess the enemy position and strength. He took out a pistol and threw away his shirt, and dove into the lake to swim across. He managed to reach the very vicinity of the Pakistani movement. He surveyed the whole area and returned after a few hours. He reported that a large number of vehicles and soldiers had been brought from Satkhira Headquarters.

As they were unsure about our strength, they were pulling all their resources from far and wide so that they could plough through our position and evict us and capture the spot. Against that, our strength was poor. We were under the open sky without protection, with intervening rain drenching us and flooding our trenches. The rain was soaking us through our scanty attire. We had no headgear on, no fixity of food supply, no assurance of the next meal. Our only guiding force was a high degree of moral strength and a deep desire to destroy Pakistani troops at any cost. That is why nobody complained; even the sick ones did not cry for medical attention.

My men who continued the fighting with me were primarily students, police, Ansar and EPR. They had no formal training in combat, no uniform, no helmet and no backpack. Thus with a band of multifaceted battle-hardened Muktibahini, almost empty-handed but a few bullets in each one's bandolier or magazines, already partially exhausted without much replenishment, I, Captain Mahbub, was caught in muddy soil in the ravishingly green surroundings of my motherland. From their movement and direction of bombs throughout the day, I felt that the Pakistanis had possibly guessed our location, but I was sure they had no idea about our strength. As the daylight cleared my view, I found no respite on either side. We were facing off the enemy as if since time immemorial. The enemy was waiting for the opportunity to locate our position. No sooner our bullets had burst than the crawling enemy Jawans went under the protection of tree trunks and ran backwards. Once continuous firing stopped, I ran to the trench where one of the soldiers shot the first shot from our side. He was a young man named Motiur, who had just joined after Chakulia training. This was his maiden battle. He was so tense that, out of excitement, his fingers pressed, and the bullets flew past. I told him that due to his naivety, our position had been compromised to the enemy. "Now get ready to face artillery bombs," I exclaimed. In exasperation, I returned to my command post.

During the enemy fire, evacuation through water was impossible. "Allahu Akbar" -- the war cry came vibrating in the ether. The firing was now coming from three sides, the intensity increasing, and our repeated requests for mortar support was not coming. Our wireless continually cried for Delta 2, but no response was forthcoming. I stopped the counter fire because I knew that if there were any big thrusts by the enemy, our bullets would be exhausted in no time. We had a very limited supply.

I was worried as I felt we were hugely outnumbered, and we were in for fistfights once we started the counter fire. Having found no resurgence from the Indian side, and as the enemy advance became louder by the second, I asked my boys to open fire as soon as the enemy came within range. They were crawling towards our position in a group. Once they approached within our range, I ordered, "Fire". All guns went into action on my order with simultaneous resounding slogans of "Joy Bangla".

I found no sign of Muktibahini, who was supposed to move ahead in action to help us. To capture the Kakdanga BOP, the Boira contingent was nowhere to be seen. The 25 odd men of the Alpha Company under Nasir, where Sattar had already suffered death due to a mine blast around Kakdanga BOP, had left their position when their ammunitions were exhausted in the face of heavy enemy fire. Our firing from all sides of the pond was more damaging for the Pakistanis as we were in the protection of mother earth in our trenches. On my side, I was trying in vain to use the mortar, which was perhaps too old to emit fire.

My batman Ali asked me to request Indian artillery support one last time, but no response was forthcoming. Momen got fed up and said, "Sir, the Subedar is already wounded in his trench, his bullets finished. Babor Ali is having a fistfight, perhaps already dead because Pakistanis have bayoneted him. We can't fight empty-handed. It is suicide, so we should move out." I called for the sector commander in this dangerous situation, but there was no response from him; without any directive, I had to make my own decision, as many of my brave fighters were already dead. I took my last available intelligent option. As per my order, everyone fought to the last bullet, like lions.

Azam Chowdury's firing destroyed one jeep of Pakistani Major Jafar Iqbal on Sonabaria-Kolaroa road. The soldiers in the jeep were killed. As a result, a severe exchange of fire ensued between Azam and Jafar Iqbal. Long-range Pakistani artillery gave cover fire to Jafar in this battle. Despite the severe damage done to Pakistanis by Indian long-range artillery, Jafar Iqbal managed to keep Azam Chowdhury at bay. In the face of a stiff attack, Azam was withdrawn by the sector commander.

When I was left alone in the lake, Pakistan radio announced me dead. They broadcasted a piece of news: "In a severe fight with Pakistani Noujawans, the ferocious Captain Mahbub has been killed". This news reached my friends in Kolkata, and they arranged a fateha for the salvation of my soul. Later on, Samad Bhai, Dr Belayet and Faruk Aziz found out that I was not dead but injured and taking treatment in Barrackpore Military Hospital, India. In the hospital, I was operated upon and treated for a gunshot injury. But my injury was superficial -- no bone was cracked, and it only cut through my muscle.

A total of 62 men and many non-combatant people participated in the war during the four days. One of the most prominent ones acting from behind were General Manekshaw, Indian Army chief of staff. He was consulted before the deployment of artillery and the stationing of troops along the border. General Jagjit Singh Aurora, GOC-in-C Eastern Command, Indian Army and General Dalbir Singh of Eastern Command, Fort Willliam, were also in the command structure. Col Nair, CO 13 Dogra Bn. Indian army was acting in harm's way. Out of the 1,200 soldiers deployed by Pakistan, 211 were killed, 331 were wounded, and 16 were captured. Some of their arms and ammunition were collected later on from the battle area.

On our side, 17 freedom fighters embraced martyrdom including Sepoy Rouf, Sattar, Naik Shafiqur Rahman, Monwar Ali, Zakir Hossain, Imdadul Haque, Habilder Shafi, Sepoy Ansar, Hamaz Uddin, Ayed, Akbar Ali Sarder and Ahad.

It is difficult to evaluate the Baliadanga battle from a holistic perspective. The lesson for us was: 'half a battle is won with proper knowledge and surprise'. In our case, our battle plan was drawn in a hurry under Indian pressure. Indian incursion was impossible under the given circumstances. Our foot soldiers were left under the reach of Indian artillery support, but it lacked at a very crucial moment when we needed it most.

Note:

Maj Gen Abul Manzoor became a general at 41. He was one of the youngest generals of the front line force in South East Asia's history. He got his PSC from Defence Services Staff College, Canada. For his intelligence, keen eye for tenacity, capability to create loyalty among the rank and file colleagues, and high sense of tactics, he was prominent in the Pakistani military and known as 'Pandit'. When the liberation war started, he escaped through the India Pakistan border, where he was posted as Brigade Major of a Pakistan Para Brigade. Subsequently, as a Major, he was posted as sector 8 commander of Muktibahini from August 14, 1971. The operation Baliadanga was his maiden battle as sector commander.

Mahbub Uddin Ahmed Bir Bikram was the Sub-Divisional Police Officer (SDPO) of Jhenaidah during the Liberation War. He was in charge of presenting the guard of honour to the Acting President of Bangladesh Government-in-exile, Syed Nazrul Islam, at the oath-taking ceremony on April 17, 1971.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments