Maj. Gen. Ishfakul Majid: Soldier & Gentleman

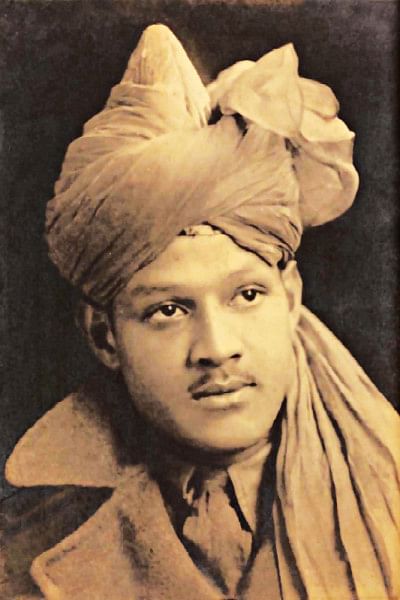

Mohammad Ishfakul Majid was born on 17 March, 1903 in Jorhat, Assam, Bengal Presidency in British India, to an illustrious old Assamese family which was arguably the most prominent Muslim family in Assam, especially during the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. It was a wealthy, titled and a well-educated family hailing originally from a prosperous mercantile class with a conservative background. The family originated from Goalpara, Assam, but had moved to Jorhat in upper Assam when the ruling Ahom Kings shifted their capital from Sivasagar to Jorhat. However, despite their financial prosperity and social standing, the Majids remained religiously devout and inclined towards Sufism. Ishfakul's great-great-grandfather, Dar Shah Fakir, had renounced worldly life and chose to lead the life of an ascetic instead. Thankfully, for the family, Ishfakul's great-grandfather, Mohammad Shah, became a prosperous merchant and the largest 'Mauzadar' (landholder) of Assam, who owned extensive arable land and residential properties in Sivasagar, Dibrugarh, Guwahati and Jorhat. Ishfakul was a nephew of Sir Syed Muhammad Saadulla (1885-1955) KCIE, the Chief /Prime Minister of Assam during the British Raj.

Ishfakul Majid's renowned father Abdul Majid (1868-1924) CIE, was a scholarly man who was proficient in Arabic, Persian, English, Bengali, and Assamese. After passing his Entrance exam with flying colors, he graduated from the prestigious Presidency College in Calcutta in 1887, and joined Cambridge University in England, to study law in 1888. He qualified as a Barrister from Middle Temple in 1891. On his return to Assam, he married Mafidan Nissa. Abdul Majid had a distinguished professional career and held important public offices throughout his life. He became a Justice of the Calcutta High Court in 1920, was awarded the CIE (Companion of Indian Empire) and given an audience by King George V, in a brief ceremony held in London. The same year he was awarded the 'Grant of Insignia' by the British Government and subsequently nominated for knighthood. He was an eminent litterateur of the Assamese language and a philanthropist who built two pioneering schools for female education in Jorhat. He maintained a fine library with a rare collection of books and manuscripts at his Shillong residence.

The Majid family owned a beautiful hill-top bungalow called 'Gulistan', which was located at Kench's Trace with a splendid bird's eye-view of the undulating hilly terrain rich in verdant foliage in the greater locale of Riblong, Shillong in Assam. It had a large compound with abundant flora and a nice cottage named 'Dunoon' for guests. A house close to Gulistan was owned by Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy, the famous physician and politician of West Bengal, based in Calcutta. It was in Roy's house that the parents of Ishfakul first met and befriended the Nobel Laureate Poet Rabindranath Tagore, who later visited their house on a subsequent visit to Shillong. The Kabiguru himself sang a few of his Rabindra Sangeet in his inimitable style for the Majid's, who were ecstatic at the honor bestowed on them and listened mesmerized. Sadly, Gulistan today is a government rest house with a substantially reduced compound.

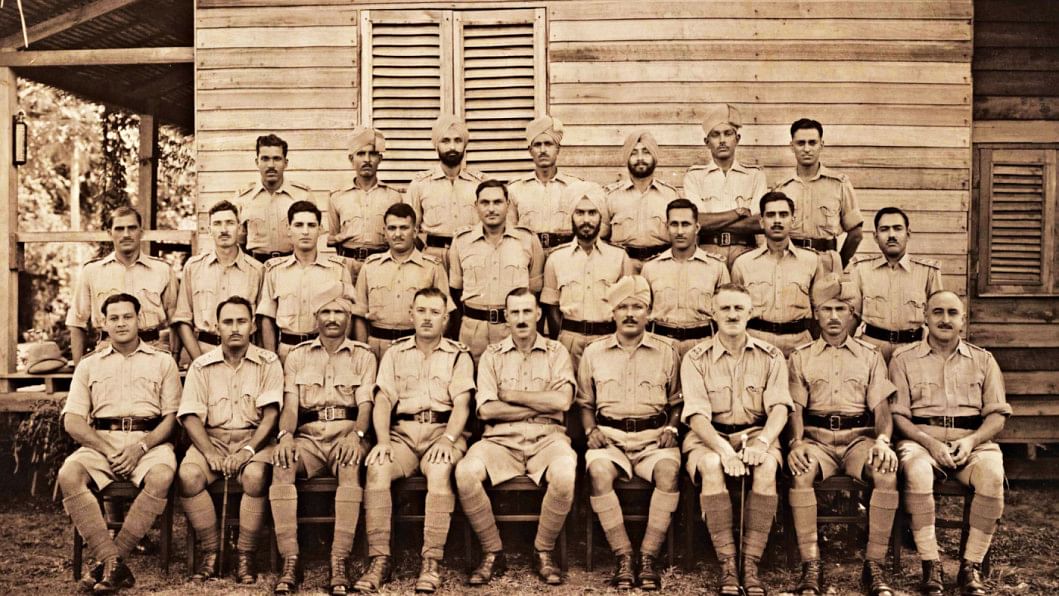

Ishfakul Majid completed his undergraduate education from the well-known Cotton College, Guwahati, Assam. On 2 February 1922, he joined the prestigious Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, England, passing out as a King's Commissioned Indian Officer (KCIO) on 27 August 1924, a rare distinction for an Indian Muslim in those early days. He was the second Muslim from the Bengal Presidency to join Sandhurst, the first being Shahibzada Iskander Mirza of the Murshidabad Nawab family, who enrolled in Sandhurst in 1918, passing out in 1920. On his commission in 1924, Ishfakul was attached for a year with the 2nd Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment of the British Army based in Lucknow and Ranikhet, India. In 31 October 1925, he was accepted for the British Indian Army, being posted to the 4th battalion of the 19th Hyderabad Regiment (later Kumaon Regiment) in which capacity he served for long years. He was promoted as a lieutenant on 27 November 1926, as Captain on 27 August 1933 and as a Major on 1 December 1941. During WWII he served in NWFP, Assam, Burma, British Malaya and Iraq attached to his favorite Assam Regiment. Two of his junior colleagues who served with him during this period were latter generals: Thimayya, KCIO from Sandhurst, 1926, and the 6th C-in-C of the Indian Army and Lt. Gen. Azam Khan, KCIO from Sandhurst, 1929, the popular governor of erstwhile East Pakistan under President Ayub Khan's dispensation.

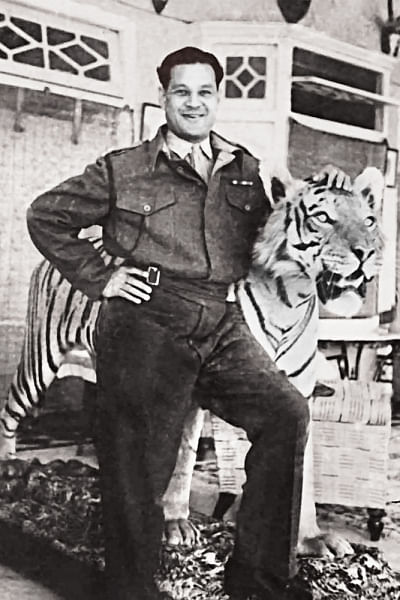

In 1935, Ishfakul married Ayesha Rahim the youngest daughter of Justice Sir Abdur Rahim, KCIE (1867-1952) of Midnapore, Bengal. Sadly, Ayesha died prematurely and childless in 1941. Her eldest sister Niaz Fatima was married to Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. Therefore, Ishfakul and Suhrawardy were brother-in-laws. Ishfakul's second wife was a veritable statuesque beauty named Zohra Raja, the sister-in-law of the Raja of Nanpara State in Baraich, now in western Uttar Pradesh. Although, Nanpara was a relatively small non-gun salute Princely Indian State, yet it was one of the richest Talukdari in British India. Ishfakul's marriage to Zohra ended in a divorce in the late 1950s, without any issue. On the eve of partition Ishfakul was asked by Nehru and Gen. Cariappa to stay back in India and remain with the Indian Army. However, he chose to opt for Pakistan instead at the behest of Jinnah and Sir Abdur Rahim. It was a fateful decision which would ruin him professionally and change his life forever. In 1947, following the partition of British India, Ishfakul already a Brigadier by then joined the Dominion of Pakistan and was soon elevated to the rank of a Major General, the first Bengali army officer to achieve that coveted rank in the Pakistan Army and given command of the 51 Independent Brigade and later on made the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the elite 9 Infantry Division (NWFP), based in Peshawar. His personal records show him as having domiciled after the partition - first in Sylhet and later at Fatullah in Narayanganj close to Dhaka. Ishfakul was fully conversant in Bengali like his father and identified himself closely with the Bengali ethos and culture. However, he was also a full-fledged 'Pucca' Anglicized military officer of the colonial vintage, one who had thoroughly imbibed the old world tradition of the 'regimental esprit de corps' being schooled in the rarified atmosphere of 'Sandhurst' as a King's Commissioned Indian Officer (KCIO). Such military officers were once regarded informally as members of the 'military aristocracy' in the annals of the British Indian Army. He spoke characteristically with a clipped English accent, his countenance defined by a stern visage and a stiff upper-lip. He was tall, fair and handsome possessing a well- built muscular physique with a formidable presence. He was very proper and courteous in polite society and could be charming in social circles. However, he was also a very proud man and lived by the principles of righteous dignity and honor, never compromising with anything that was inherently wrong or improper. Once as a young army officer in the British Indian army, he suddenly came across a British manager at a tea garden in Assam manhandling a poor Indian coolie. He instantly stopped his jeep got down and soundly thrashed the manager. Such an audacity by an Indian was unheard of in those days in colonial India. Fortunately, no action was taken against Ishfakul given his family background, the merit of the case and the nationalist fervor already gripping the country by then. It is to be noted here, that Ishfaqul was physically very strongly built. An avid sportsman, he excelled in physical sports and was a good boxer. He was also a big game hunter of tigers and rogue elephants. However, it is also true that in the early years of his service in the colonial army, his British superiors have often mentioned his 'temper flare-ups' in his 'Annual Confidential Reports' (ACRs) and advised him to consciously mend his ways, besides highlighting his positive attributes which were rather praiseworthy for an upcoming young Indian army officer.

Postscript: Pakistan's adventurism in the princely State of Kashmir in 1947, led to the Kashmir imbroglio during Jinnah's tenure as Governor-General. It thrust the Pakistan army into the center stage in national affairs, with unending negative repercussions for the new state. It emboldened the army which became ambitious. Jinnah passed away in 1948, catapulting Nazimuddin to the Governor-Generalship. In paper it appeared to auger well for East Bengal in terms of representation at the very top. But the position was largely ceremonial and Nazimuddin was known to be weak and indecisive. Thus, the brunt of governance and the inherent contradictions of an improbable new state, was increasingly felt by Liaquat Ali Khan the Prime Minister (1947-1951), who had to contend with the growing restiveness in the army following the Kashmir debacle. Liaquat being a migrant (Mohajir) from the UP, did not enjoy any political constituency in Pakistan. At this period the top most bureaucrat wielding considerable authority in the new state was Maj. Gen. Iskander Mirza a scion of the Murshidabad Nawab family, with a penchant for intrigue and duplicity imbibed as a political agent with long years of experience under the British Raj. Iskander too, was a calculating and ambitious man. He became the Defense Secretary (1947-1950) which was a powerful position viz-a-viz the fledging army. However, Iskander too did not have any political base in Pakistan as an immigrant. Therefore, he aligned himself with the likes of Ayub (a son of the soil) for support who was a rising star in the army, and already endorsed by the Americans as 'our man' by 1950, at the sudden death of Maj. Gen. Iftikhar Khan in a tragic plane crash in 1949. Iftikhar was touted by Gen. Douglas Gracey and the Pakistan government as the tentative new native C-in-C of the Pak army, with the retirement and departure of Gen. Gracey as the last British C-in-C of the Pak army. Besides, Gen. Gracey had incurred the displeasure of the top native brass in the Pak army for his presumed neutrality during the Kashmir war. However, it remains unclear as to the criterion by which Maj. Gen. Iftikhar Khan was tentatively tipped-off for the top post as C-in-C, being junior (commissioned from Sandhurst in 1929 as KCIO) to a whole bunch of officers senior to him. Ayub refutes this story about Iftikhar's tentative selection as unfounded in his autobiography.

Finally, in the run up for the top position of C-in-C of the Pakistan army, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali finally selected Ayub bypassing three other senior eligible aspirants for the coveted post : Major General Ishfakul Majid, Major General N. A. M. Raza and Major General Akbar Khan Sr., (senior most as per PA-1). Ayub's surreptitious elevation clearly contravened the stipulated procedural norms of selection in the Pak army, thereby setting an unfair and bad precedent. However, Ayub's candidature was strongly endorsed by Gen. Gracey and Iskander Mirza, who actually played a pivotal role behind the scene, which was finally okayed by Liaquat himself, being charmed by Ayub's guiles. Conveniently forgotten was the fact that Ayub was not only the junior most amongst the nominated lot, but had a disgraceful record at the Burma Front in WWII, where he was 'unceremoniously' relieved from command of his regiment and temporarily suspended without pay for 'tactical timidity' and 'visible cowardice under enemy fire', when the Japanese had made a determined attack. Besides, Ayub's name was not even mentioned in the original list for the position of C-in-C, but somewhat hastily added later. Therefore, a gravely disappointed Ishfakul decided to resign. At the same time the infamous 'Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case' of February, 1951, led by Maj. Gen. Akbar Khan Jr., hit the headlines and although Ishfakul's name was never mentioned in the formal charge-sheet of the alleged accused, Ayub tried his best to implicate him. However, with the legal assistance of Suhrawardy, Ishfakul was honorably acquitted and all his perks and privileges were returned to him. But by then, he had already made up his mind to resign from the Pakistan army. He loathed to serve under a 'crook' like Ayub, who was years junior to him. Given Ishfakul's temperament, I am inclined to believe that he not only desisted from congratulating Ayub on his assumption of office as the C-in-C, but may also have said something uncomplimentary to his face. He was known for his guts. As a senior officer he was used to addressing Ayub by his first name. Ayub too, must have felt decidedly uncomfortable with Ishfakul around. Therefore, he had tried his best to neutralize him.

An embarrassed Pakistan government offered Ishfakul top diplomatic assignments and, even the option of joining the corporate world. But he adamantly refused all such favors. He moved to Karachi where he bought property in Clifton and drove a Hillman Minx car up until 1961. Finally, he decided to sell off his property in Karachi and move to the then East Pakistan, where he built a modest house on a plot of land in Fatullah, Narayanganj, close by the river Sitalakhya and settled down. He married Begum Marium Ladli his third wife in 1961, who hailed from old Dhaka. Since they did not have any issue from this union either, the couple adopted a daughter who, later, settled in the USA.

In 1968, Ishfakul Majid became the Honorary Secretary of the East Pakistan Retired Soldiers Association with Col. M. A. G. Osmani as its President in Dhaka. At the height of the Non-Cooperation Movement in March 1971, Ishfakul and Osmani led a procession of retired Bengali army officers and soldiers from the Baitul Mukkarun Mosque to the Shaheed Minar and thence to the house of Bangabandhu in Dhanmandi, to pledge their allegiance to his leadership and unconditional support to the ongoing movement. They also presented Bangabandhu with a ceremonial sword. A historic photograph clearly showing Osmani and Ishfakul leading the procession of retired Bengali army personnel in March, 1971, was prominently displayed in all the Dhaka newspapers. After the Pak military crackdown on 25 March 1971, Ishfakul was arrested by the Pak Army from a Dhaka street in July, 1971while driving his car. He was taken to the then 'second capital' and held captive for some time, interrogated and tortured. He was already 68 years of age. The army authorities intensely pressurized him to give a false statement against Bangabandhu denouncing him as a traitor, which he steadfastly refused to comply with. They further sought his help to lure Osmani into reaching some sort of compromise with the Pakistani establishment which he again stubbornly refused. Exasperated at his dogged refusals to do their bidding, Ishfakul was sent to the Dhaka Central Jail where he was held in isolation and finally released in August, 1971. Many years later, I heard from a reliable source that a couple of Pakistani officers in the rank of Colonels entrusted with Ishfakul's interrogation, were at times greatly embarrassed when Ishfakul had berated them in unequivocal terms to mind their manners while addressing him. After all, the Pakistanis were fully aware who they had taken on, that is, one of the senior most retired Maj. Gen. formerly of the Pak army, who was moreover a Sandhurst trained commissioned officer of 1924, and thus four years senior to Ayub Khan!

After the liberation of Bangladesh, Ishfakul Majid, by then in poor health from the shabby treatment meted out to him by the Pak army, was sometimes seen in the company of Gen. Osmani many years his junior who held him in great regard. Ishfakul once again refused all offers of diplomatic or corporate jobs proffered to him. He just wanted to lead a quiet life in obscurity by the riverside in Fatullah. He died of prolonged illness at the Combined Military Hospital in Dhaka Cantonment at the age of 73 years in 1976. The finest eulogy was paid by Gen. Osmani who knew him well. Ishfakul Majid was buried with full military honors at the Azimpur graveyard. Gen. Osmani personally saw to it. And, after the guns were fired in a final salute and the last post played in a plaintive tribute, a senior officer of the Army Medical Corps (AMC) remarked wistfully that on his deathbed, a misty eyed Ishfakul Majid had told him of a recurring dream where he saw himself once again as a young cadet at Sandhurst, waking up to the haunting early morning call of the buglers, to fall-in at the parade ground!

Waqar A Khan is the Founder of Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments