Legality and legitimacy of Bangladesh Constitution

What is the source of legality or legal validity ('Boidhota' in Bengali) of a constitution? A superior law? India and Pakistan got their independence and established two constituent assemblies via the enactment of the Indian Independence Act, 1947. This Act was passed in the British parliament in Westminster. So, the Indian Constitution of 1949 and the Pakistani Constitution of 1956 got their validity from an Act of the British parliament.

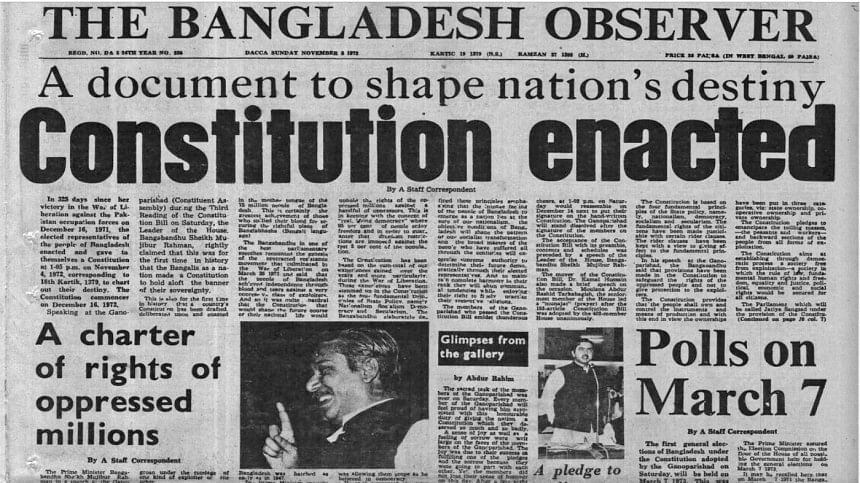

All the members of the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh were elected under the Legal Framework Order, 1970. Was that Order the source of legality of the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh? The answer is no. The reason is that the Legal Framework Order, 1970 arranged elections for making a constitution for Pakistan, not for Bangladesh. This fact was not denied in the Proclamation of Independence, 1971. The Constituent Assembly of Pakistan was 'arbitrarily and illegally postponed for indefinite period' and 'Pakistan authorities declared an unjust and treacherous war'. Until the very war, the representatives of Bangladesh tried to make a constitution of Pakistan. The just and successful war established the Constituent Assembly as a sovereign and independent authority for Bangladesh. Hence, Justice Badrul Haider Chowdhury called Bangladesh Constitution an 'autochthonous constitution' in his opinion in the case of Anwar Hossain Chowdhury v Bangladesh (1989) BLD (Spl) 1, because it got its power not from the above i.e. the colonial superior authority, but from the very people.

One might argue that Bangladesh got its validity from the above i.e. from international law because Bangladesh declared independence 'in due fulfillment of the legitimate right of self-determination of the people of Bangladesh'. The right to self-determination is a right recognised in public international law. Hans Kelsen argues that a domestic constitution and international law are part of the same legal system where international law is above i.e. hierarchically superior to the domestic constitution. The Constitution of the United States of America also got its validity from the above. But this above is not international law, but natural law (God). This might be called a transcendental argument. The other argument might be called social contract argument. The idea '[w]e the people', although fictitiously constructed, expresses the general will. The validity of the Bangladesh Constitution came from it. The representatives of the people of Bangladesh constituted themselves into a Constituent Assembly because '[w]e the elected representatives of the people of Bangladesh' had the people's mandate. Later their authority was not successfully challenged.

Carl Schmitt would argue that if a constitution is not successfully resisted, it will be considered as accepted by the people. The opposition parties failed to resist it. The question of successful resistance and revolution is not a question of law, but a question of politics. A certain kind of politics would give birth to a certain kind of constitution. One might ask what the role morality plays in this regard. The answer is that politics might be influenced by morality.

Yuval Noah Harari thinks that '[w]e the people' is a useful fiction. It resides in our imagination and gives meaning to our lives. I quote from Harari's Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (2015): "The value of money is not the only thing that might evaporate once people stop believing in it." He asserts that nation and religion are also fictions. Antonio Gramsci's idea of hegemony is a concept closer to it. The civil society members tell a network of stories to the poor people and get their consent. If you want to grab the power, you need to tell better and credible stories.

Everything evolves. So does the constitution making process. Earlier people's participation in constitution-making process was very limited. But the scenario is changing. This change might be characterised as the constitutional evolutionism. We might insist that the draft Constitution of Bangladesh should have been sent to the people for getting their approval via plebiscite. But it did not happen. Even the proposal of Suranjit Sengupta to send the draft Constitution for assessing the public opinion was rejected by the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh. It did not destroy the legality of Bangladesh Constitution but weaken its legitimacy.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had a huge popularity in 1972. Neamat Imam comments in his novel The Black Coat (2013): "Sheikh Mujib was more popular with Bangladeshis than Mohammad the prophet; he was supported by people of all religions and creeds." Whatever constitution his party made would have been accepted by the people in a plebiscite. Still this process would have created a new precedent to help the future generations avoid abusive constitutionalism by way of constitutional amendments for the party interests and, in most of the cases, without having proper public deliberation.

The writer is an academic researcher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments