Killing the false woman: ‘The Harpy’ dissects parenthood, femininity, and domestic abuse

A book's epigraph usually either leaves you droplets of hints of what's to come or purposefully perplexes, with abstract quotes that leave you feeling rather than knowing. Megan Hunter's The Harpy (Picador, 2020), a mesmerizing, disquieting tale of suburban infidelity, starts with quotes from Virgil and post-structural feminist writer Hélène Cixous. And if you weren't familiar with either author, the quotes themselves will very much set the scene, and tone, of Hunter's psychological-magic-realist-fiction.

"It is the last time", the novel's first line reads. "He lies down, a warm night, his shirt pulled up, his head turned away." Within moments the reader can grasp the style, the tenor, a certain kind of content that might soon come gushing out. "Jake is not squeamish: he is like a man expecting a tattoo. […] His eyes are closed: not screwed shut, just closed, like a skilful child pretending to be asleep." By the turn of the first page the reader can sense not only the story—that of a mother of two finding out, through a succinct phone call, that her husband has been having an affair—but the way the story will come to us: in images, a flash of words, a string of thoughts—bad thoughts, understandable thoughts, horrid, horrible thoughts you wouldn't want getting out. We receive these clear images and sounds, and are left to observe and comprehend them as we like. "I lift the razor", reads the closing line of the prologue, "and a fairy-tale drop of blood escapes from under the silver."

The titular harpy, a half-bird, half-woman creature of classical mythology, is a long-time subject of interest for Lucy, the narrator, the aggrieved. She had studied the creature through school and college, and had almost finished her PhD on it. The legendary creature, now used commonly as an epithet to describe an ill-tempered woman, a "shrew", was originally simply the personification of storm winds and thunder. Throughout history, harpies have been interchangeably described with beautiful poetry and hateful scorn. "Bird-bodied, girl-faced things", as Virgil defined them in the epigraph, with a sneering selection of adjectives and verbs to go with: "abominable", "droppings", "talons", "haggard", "hunger", "insatiable".

Like one may fixate on a character, a myth while coming of age, like a Dora the Explorer or a Ted Bundy, Lucy fixated, obsessed over the harpy almost from the moment she first encountered them: as a child, her mother reading to her from an illustrated book concerning unicorns. The harpies there are more of the antagonizing nature, but Lucy is awestruck. What is a harpy, she asks her mother, a pitiful, mostly disagreeable character in the haze of the novel's memories. "[S]he told me that they punish men, for the things they do."

"There is a trail of anger flowing through my bloodline, from my great-grandmother, to my grandmother, to my mother, to me." The novel asks, and is equally stumped by, the question of where a family ends and one begins. To what extent can selflessness be driven; when does selfishness begin?

Hunter's sophomore novel is at its best when it ponders this, which it commendably does through actions more than words. My teacher, who has assigned this book and whose praise for it is repeated multiple times in the jacket and opening page, likens The Harpy's prose with the Kuleshov effect, a practice in film which presents the viewer with only a key few images, leaving interpretation solely on the viewer's part. It is, in other words, a more extreme form of 'show, don't tell', and reading this novel it is apparent the writer's proficiency in this practice. Similarly apparent is Hunter's background in poetry, which often pushes through the prose to take centre stage.

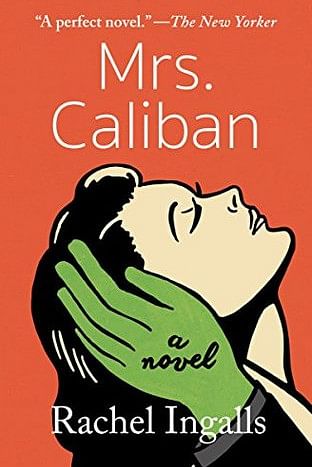

While there is no faulting the rich writing and provocative left-of-fable narrative, the overall reading experience, I felt, could've been improved with some condensing. When the novel is approaching its middle point, it repeats itself more than it should. Comparing its 193-page count with the more direct 117 of Rachel Ingalls' fantastic Mrs. Caliban (1982), which tells a similar story, if by feel more than plot, it is evident that such a tale benefits a great deal from brevity, letting the quick, impulse-like storytelling take a firm hold of you before the downs of the rollercoaster pulls you in from start to finish.

Mehrul Bari S Chowdhury is a writer, poet, and artist. He is currently pursuing an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Kent and has previously worked for Daily Star Books.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments