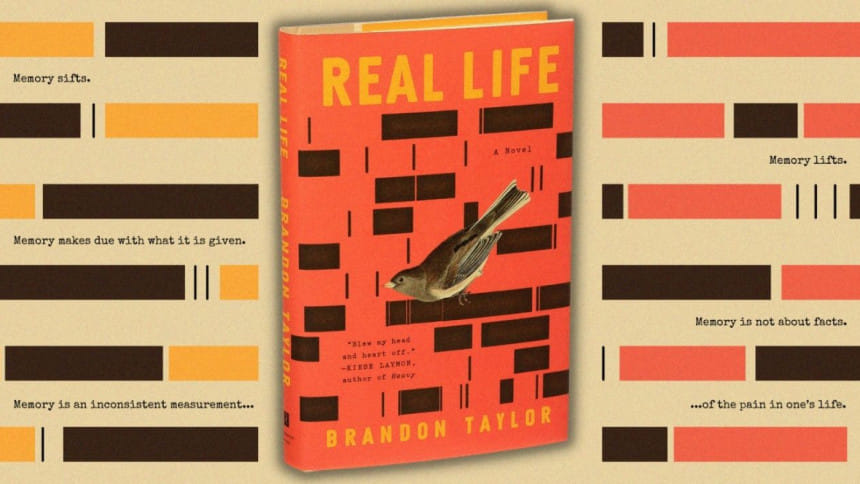

Brandon Taylor’s ‘Real Life’—It’s seldom fair.

Brandon Taylor's Real Life (Riverhead Books, 2020) begins with the protagonist, Wallace, contemplating his father's death and feeling lonely amongst his friends because they do not understand the experiences he has had. The novel's exploration of "real life" over the course of a weekend is also one that unpacks identity, race, sexuality, and the sheer boredom and frustration of postgraduate life.

Wallace, somewhat like Taylor himself, is pursuing his postgraduate studies in the STEM field at a Midwestern college town. The ennui of his long days at the lab followed by the cold hostility displayed by his postgraduate peers seem only to amplify the melancholy of his experiences as an introverted, queer Black man. Commentary on campus life in this book takes the form of characters like Dana, who makes Wallace feel like an impostor, and his advisor, Simone, who undermines him. His friends, also postgrad students, similarly discuss their college lives and act as forces which propel Wallace to confront his own opinions and demons.

A graduate of the prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop and shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize, Taylor's writing flows—he weaves one into his story and hardly allows its heavy themes to render the book boring or stagnant. Instead, the smoothness of his prose mirrors the flow of the life he is trying to emulate. The indifference of Wallace's tone is reminiscent of the disconnect with which we treat ourselves when we are letting our lives wash over us, when we let life happen to us without actively participating in it because we are too weary.

And on that note, the novel's perspective on life, or rather, real life, is a pessimistic one. I could feel it build—Wallace's unhappiness catching up to him, forcing him to reckon with it, but even in heightened moments of emotion, he refrains from confronting them. We feel the desolation at dinner parties where he is the victim of casual racist jabs from his friends, most of whom are white. Even the lab serves as a place of alienation—his coworker, Dana, constantly trying to belittle him, Wallace feeling "insecure" and "uncertain."

Wallace's feelings of alienation are further exacerbated by an event much more acutely tragic. Flashbacks from his past suggest sexual abuse and trauma. Yet, although Wallace's past trauma serves as one of the major elements of the plot, Real Life is hardly defined by it. Instead, at its core, the novel is a thorough examination of how the many identities that conflate and converge in Wallace succeed or fail in defining him. No part of his character is left unexamined—Taylor examines and re-examines Wallace's traumas, his hurts, his disappointments, his ability to blend in, and his inability to do so when everything is too much, everything is laid out intricately for one to see as starkly as he sees it himself.

It is this intricate and often meandering study that allows Taylor to present to us how Wallace's experiences as a poor, millennial, queer Black man intersect. Wallace's character is true—not from a lens of moral virtue but instead from an absence of it. Although Real Life could have comfortably occupied the niche of the millennial novel with a flawed or wronged protagonist who is unflawed and un-wronged at the end of the novel, it refrains from doing so. What we get, instead, is a man trying to grapple with the death of his hopes and expectations about the place he has fled to. It goes on even when characters are not granted the moral closure they might deserve.

Miftahul Zannat is fascinated with the human ability to analyse words with more words. When she is not busy reading or watching films, she likes writing about the things she reads and watches.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments