The Christmas the Kolis took to cricket

London

The year is 1721. There are Indians, many no doubt Bengali, visible on the streets of London, some settled down there, others at a loss, mostly sea-farers off the East India Company ships bringing the Indian fabrics that have become all the fashion, silks worn by the rich, cottons by the poor.

The London weavers are so fearful of losing their jobs they are rioting, throwing acid at the women who continue to wear the colourful Indian calicoes, tearing them off their backs in the streets. India House is cordoned off.

Daniel Defoe is remembered now as the Father of both the English Novel and Journalism. It is as the worst kind of paid hack he writes a rabble-rousing pamphlet calling for an Act of Parliament to stop what he calls the Calico Madams from wearing Indian fabrics on penalty of a fine. The Act is passed in 1721 – the beginning of a long road leading to the destruction of the great Dhaka weaving industry.

The Gulf of Cambay

Equally unfamiliar, perhaps, to those of us who come 300 years later and know what happened during the British Raj, is the scene on the west coast of India in 1721. There, as elsewhere, the East India Company, seeking the fabrics that are so eagerly sought after in London, are on the edge. They are clinging precariously on to Bombay, its population ravaged by plague and the Maratha navy smaller than at any time in its sixty years in their possession.

The Mughal satraps and resurgent Marathas are the real powers in the region, struggling for supremacy. Marines routinely desert the Company ships to serve one or other of them, if not to join one of the several competing European trading companies, the Dutch the most prominent.

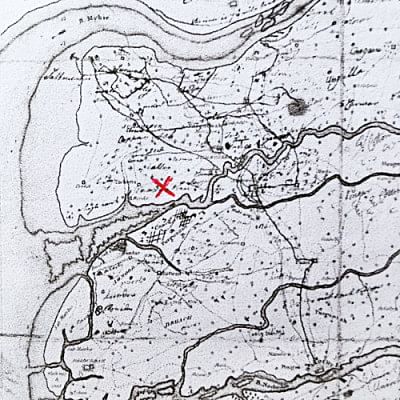

Along the coast, the Company is quite literally all at sea. Tacking from the western Bhavnagar side of the ever-shifting, ship-wrecking Gulf to the eastern Jambusar side, as they try to access the fabled entrepôt of Cambay 30 miles further north at its head, the Company's boats are subject to constant attacks by sea-faring Sanganis from Beyt, in Kathiawar.

Suddenly, in the middle of the constant warfare, we catch sight of the first known cricketing on Indian shores. Probably there were other cricketings on other rivers, the Hooghly and the Padma among them, but such a lower order game had been going on in England for a century without any notice being taken of it unless it led to lawlessness.

The cricketing in 1721 is taking place on the banks of the Dhadhar, just upriver from Tankaria, the lading place for Jambusar district. This is of increasing importance because Jambusar is, with Bharuch, the most productive cotton-growing district in Gujarat. It is also becoming the handiest place to moor for Cambay, erstwhile port for Ahmedabad and trade as far inland as Agra, but silting up and subject to violent spring tides.

The Ships

It is the beginning of December. The Company sloop, the Emilia, a small boat used for ceremonial purposes as well as trading, arrives on the river from Bombay. The Emilia usually protects smaller trading craft but on this occasion, because there have been successful attacks off Surat by Kolis, it is itself accompanied by a larger galley, the Hunter.

The crew of the Hunter has been reinforced – unusually - by a dozen marines off the London, otherwise required to support a vain attack on Maratha-held Alibag. The Emilia has a crew of 20, three Europeans and 17 Indian marines. The Hunter, with reinforcements, has a complement of some two dozen Europeans, not all of them British, and five dozen Indians.

These two ships lay up on the Dhadhar while their captains, Hearing and Doggett, having missed the spring (full moon) tide that could have taken them over the bar, go up to Cambay in a gallivat or tender, crewed by some thirty rowers and twenty marines.

Hearing's predecessor as captain, Sedgwick, met his end killed by Kolis he inadvisedly fired on when aground at the mouth of this river. His successor, Woodward will be drowned when shipwrecked in the treacherous tides off Cambay.

The shores of the Dhadhar do not promise any safer refuge for the 20 or so Europeans and some 50 Indians left under the command of Lieutenants Rathbone and Stevens off the Hunter (itself destined to be blown up two months later in an engagement with Angria's grabs off Bassein).

If the marines moor far enough upriver to be free of hit-and-run attacks from Sanganis and Sultanpuri Kolis at sea, they are now vulnerable to lightning raids from Maha Kanti Kolis on land. As the Company's long-time broker, Laldas Vithaldas Parikh, says with commendable understatement: How ticklish the times are.

The Cricketing

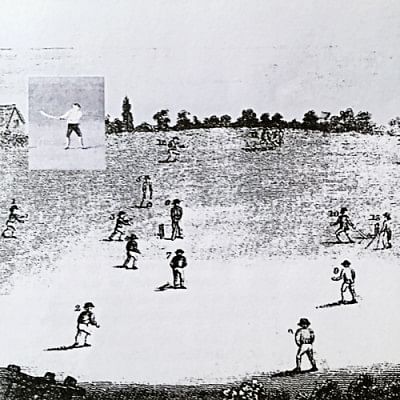

For a fortnight or so, the marines engage every day at playing cricket and other exercises, on their toes the whole time for battle off the field as well as on.

Cricket is a people's, not a gentleman's, game. Marines off the London probably get it going. The ship has sailed from Gravesend, the press-ganged farm boys and artisans from the Downs thereabouts known to be the best and keenest cricketers in an England where cricket is so far played only in the counties adjoining champion Kent. They have to teach the others, English and Europeans as well as Indians, how to play this emerging game.

Even in Kent, cricket is frequently combined at festive occasions with other pastimes. On the Dhadhar it is the run-up to Christmas (and a number of crew are topasses or Indian Christians) and an air of prolonged recreation takes hold such as would horrify the Directors of the draconian East India Company.

The marines are camped out in the mango groves that locals say are married to wells. There is fresh water and pasturage. Nearby are the cotton plantations, with intermediate crops of chickpeas, millet, oats other grains attractive to foraging antelopes and sparrows. The plantations are bordered by tamarinds, a sanctuary for peacocks, though not for the Indian crew who believe these trees are unhealthy to sleep under.

The recreation is not mere recreation: it is military exercise. The Company requires all its citizens in Bombay to drill like a militia – or, if pacifists, to pay a heavy indemnity. The cricket and other exercises on the Dhadhar serve as drill, not only to keep the marines fit but as a showpiece, to deter interference. All those parading under the colours of the Jack (flying on a pikestaff) have to be involved, without exception.

The marines anticipate attacks from hostile local Kolis and the cricketing has a ring of fielders facing out out as well as in, the players keeping arms (if not helmets) to hand on the field. Local settled Talapda, if not raiding Chunvalia, Kolis, do come to spy out the scene of the cricketing and are evidently intrigued for they return several times.

What they see is a target strangely low on the ground composed of two forked sticks topped by a longer one. A marine with what looks like an oar curved at the bottom defends this target from another marine throwing something like a cannonball at it. When the oar strikes the cannonball, there is a lot of confused shouting and running and a ring of marines converge on a hole in the ground beneath the target, the only time there chance of physical contact.

This Koli view of cricket as mock warfare is shared by respectable citizens in England who, for a century, have regarded it as a lawless activity of the lower orders, conducive to rowdiness and ill behaviour. Cricket is still liable to be stopped by a magistrate lest it occasion riot.

The local Koli agriculturalists are joined on several occasions by processions coming down from commodious Jambusar, headed by prominent citizens on horseback, Dharala Kolis to the fore brandishing bamboo lances and the best Bharuchi swords and shields, a veritable Bharat Army.

The Gear

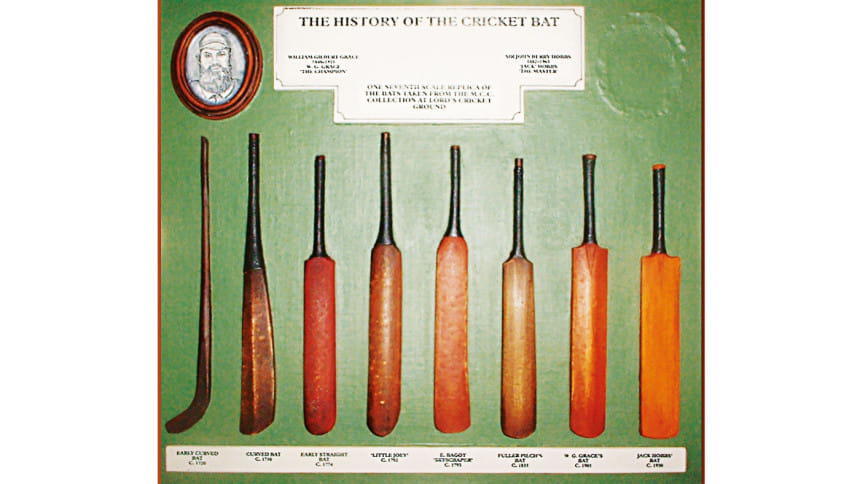

Bat and ball, stumps and bail might have been found stowed in a locker on the London but the London is back in Bombay. Instead the ship's carpenter is put to work.

A cricket bat need not be made of willow. A variety of woods have been used as they are in baseball. The year 2021 has seen the creation of a bamboo bat by Darshil Shah, a Thai international cricketer whose family originally hails from the head of the Gulf of Cambay.

While bamboo was widely used on the Dhadhar as planking for combat craft called grabs and as lances for the Dharala Kolis, the ship's carpenter on the Hunter – and Surat is famous for its carpentry – has easier wood to work with than bamboo. To desecrate the revered banyan to hand on the shore is unthinkable but maybe both mango and tamarind are tested and found serviceable. That is, if the carpenter doesn't resort to his supply on board.

The ball has to be suited to under-arm bowling, deliveries skimming and bumping along the ground. An untouchable leather ball is already known in England but perhaps not always packed with horsehair on cork. Wood alone may suffice on the Dhadhar: if wrapped at all, with yarn or cotton-wool and a covering of sailcloth. Or, simply the tar that is so plentiful on board it is a slang word for a sailor.

The length of the wicket is the country chain or twenty-two yards. There are no boundaries, not even the milkbush hedges, and every run has to be run. The weather is cool, the trees shady, the games not confined to early morning or evening.

The Players

Nobody on the Dhadhar needs to argue about who will be captains. In a tradition that will later take hold in Indian cantonments, the two young Lieutenants left in charge pick the teams, ringing the changes over a fortnight, their own enlisted Kolis from Bombay taking a turn to face inwards as well as outwards.

Unlike Captain Russell in the film Lagaan but like Captain Hearing and the source for our story, Able Seaman Downing, Lieutenant Rathbone shows himself to be respectful of local customs and sensibilities. Downing admires the Kolis for their independence of spirit: all parties respect the Gulf's Gogharis for their unyielding bravery. There is no reason to except anyone from the exercises, including cricket.

Whatever else, the cricketalia proves to be a welcome diversion amid so much death and destruction. Encouraged by the unexpected tranquillity, a party of marines, albeit armed, heads out two or three miles to a settlement, probably the village of Tankaria, to try and purchase provisions for Christmas.

Two of the party among the Son or Meta Kolis recruited in Bombay speak the local dialect and the Patel agrees to trade so long as they behave civilly. Bartering takes place in the shade of trees outside the village. Two bullocks are bought for rupees 20/- each, two sheep at rupees 2/- apiece, along with a dozen fowls, a hundredweight of flour and some butter.

The trading being completed in an agreeable atmosphere, several Dharala Kolis begin sweeping and cutting with their swords and one of the interpreters suggests it is high time to return to the ships. As Rathbone sends a detachment ahead with the provisions, perhaps a thought crosses his mind. These people came to watch us at cricket, he thinks, is there a Koli who fancies himself as a batsman?

John Drew is the author of India and the Romantic Imagination (Oxford India).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments