When the mind says yes

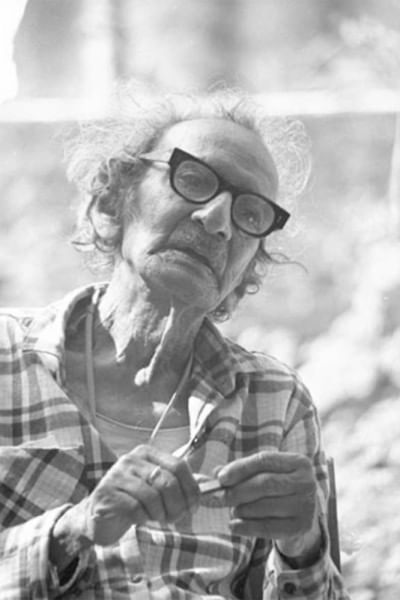

It was in the foothills of the Himalayas that he was born. In a bullock cart amid a snowstorm. It was in the cold chill of January, in the severest winter in Bangladesh's memory, that he died. Alone and uncared for, the frail old man shrunken with age, but with a heart as wide as the ocean, and a mind as young as the children that he loved, Golam Kasem, nicknamed Daddy, died at the tender age of 103. The single-storey yellow building at 73 Indira Road, with its unkempt garden, was home not only to Bangladesh's oldest photographer, but also the first Bengali Muslim short story writer.

Born on November 5, 1894, Daddy lost his mother shortly after birth. Raised by his aunt, the young man took up photography the way many young men take up many things—to impress a young girl. She had promised to cook for him if he could develop a film that others had failed to. Kasem embarked with the same trait for disciplined research that he maintained till his death. He went around the studios of Medinipur to find out the method that would win him his meal. He never talked of what the meal was like, but did describe how he used a hardener to prevent the emulsion from peeling off. Saving his bus fare to school to buy a brownie camera, he began taking photographs of the things he loved most: animals, flowers and children. And most importantly, he preserved those negatives. In his archives, amid old paper sachets marked in his neat handwriting are glass plates dating back to 1915. The harbour in Calcutta, early steam engines, the Gurkha regiment in shorts, and many many portraits. Period pieces lit in that soft natural light that early studios used.

Grainless negatives of people, generally in studied poses. His spontaneous pictures were those of animals and children, and among them are some gems. "Her first dance" is a delicate photograph of a child amid a twirl, centre stage with her family as an audience. Strong portraits of his friend, a teacher, and the calm portrait of his grandmother belie the fact that he was an amateur who took photographs for fun. He sold his first photograph at the age of 98, for Drik's 1991 calendar.

The founder of the Camera Recreation Club, Daddy arranged regular meetings at his house in Indira Road where the club was housed. Regular visitors included poet Sufia Kamal, painter Quamrul Hassan, and photographer Manzoor Alam Beg. His letters were hand-written, each one numbered, and the envelopes were often made of recycled newspapers or book wrappings. Competitions at the Camera Recreation Club were unusual events. Photographers who would abstain from many local competitions would submit those small 4″x5″ prints. And they were proud of the simple prizes they sometimes won. The prize giving was always accompanied by a cultural programme. And Daddy would always sing.

The room next to his bedroom was his darkroom. A red plastic bowl stuck under a light bulb—his safe light. He mixed his own chemicals from old tins of chemicals. Often, I would get an SOS—in the same neat handwriting, asking for potassium ferricyanide or some other chemical that he needed for his latest experiment. Photography was his passion. Once during a meeting at the Bangladesh Photographic Society (BPS), where he had been presented a new camera, Daddy spoke of how the camera he had been given would be much more than a machine to him. He talked of how he kept his camera next to his pillow when he went to sleep. How, when he was sad, he would speak to it, and that it would talk back and comfort him. Unimpressed by the modern motor-driven models, his preference was a simple manual SLR, "preferably not too heavy," he would add with a mischievous smile.

That is not to say he was shy of technology. I remember him holding up his thick glasses to read his first email from his grandson in Canada. He asked me to come back the next day, and as I parked my bicycle by his rose garden, he was ready with his answer, again written in his neat handwriting. He was fascinated by email and used it regularly, and curious about how the message would get through the ether.

Daddy was fiercely independent. He cooked his own meals, fed his dog and cats, and did his own shopping. Until recently, he would even go on his own to a house down the road and guide himself up the stairs to meet a lady friend whom he occasionally visited. Rarely would he talk of himself, and it was only in passing conversation with the late Nasiruddin that I discovered that Daddy was the first Bengali Muslim short story writer. He used to write regularly for "Saogat," and continued to write, both technical articles on photography for the BPS newsletter, and short stories for general publication. His last manuscript, a simple manual on photography, sadly lies in my hands, unpublished. He had dearly wanted it printed before he died. The proofing was complete, the photographs selected, but "matters of consequence" allowed other projects to take precedence. His last note, urging me on with the publication, will forever haunt me.

Always articulate, on his 100th birthday, at the opening of a joint photographic exhibition by him and the other photographic guru Manzoor Alam Beg at Drik Gallery, he talked eloquently of how photography was the way for people of the world to make friends, to break barriers, to discover one another. Later as the chief guest at the opening of the 1996 World Press Photo Awards, he talked of his own struggle to overcome the limitations of an ageing body. "My body says no, but my mind says you must, and in the end, it is the mind that wins." On January 9, 1998, the body finally said no and the mind took wings.

Shahidul Alam is a photographer and an activist, and founder of Drik and Pathshala South Asian Media Institute.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments