Michael Madhusudan Datta: Resistance, Rebellion, Rupture

I shall come out like a tremendous comet.

—Michael Madhusudan Datta

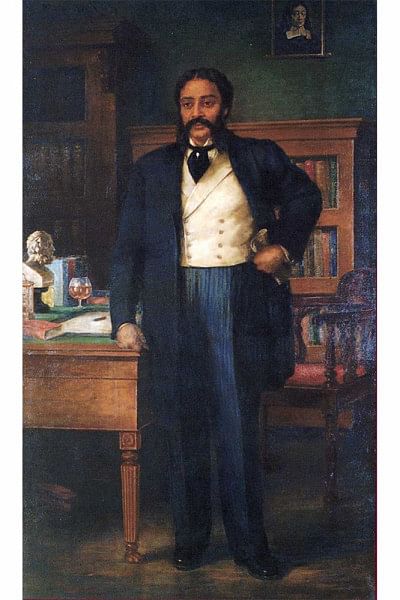

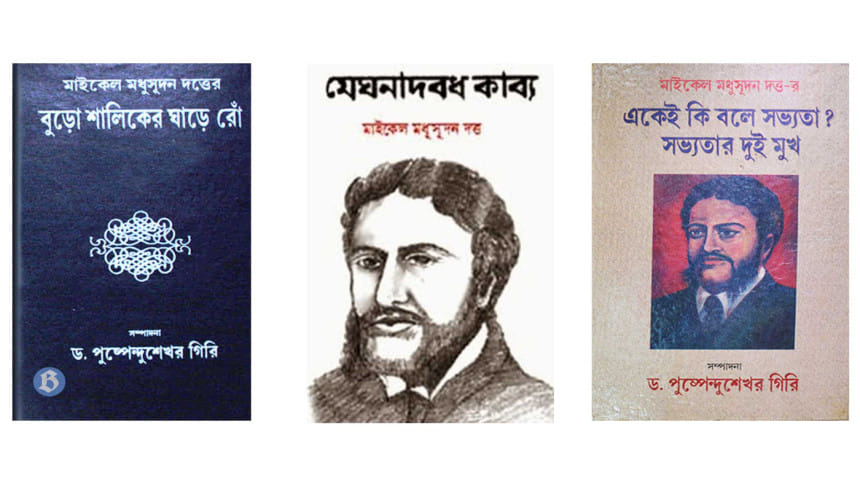

Michael Madhusudan Datta (1824-1873) is widely regarded as the first modern Bangla poet. Well before Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899-1976), Madhusudan is even reckoned as the first rebel poet in Bangla literature, although he is by no means a revolutionary like Nazrul. A relentless experimenter with both indigenous and Western poetic forms—and a veritable polyglot with a command over not only Bangla and English, but also Sanskrit, Persian, Urdu, Tamil, Telugu, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, German, and Italian—Madhusudan introduced the sonnet in Bangla poetry, while he is also considered the first modern playwright and the first successful writer of a tragedy in Bangla. Best known for his magnum opus called Meghnadbadh Kabya (The Poem of the Slaying of Meghnad)—the first Bangla literary epic that inaugurates a rupture with all preceding poetic and metrical traditions while introducing the famous amrittraksarar chhanda (unrhymed meter) that blasts open the continuum of the traditional payar cadences and couplets—Michael Madhusudan Datta exemplarily enacts the dialectics of tensions and transactions between colonial modernity and indigeneity.

In fact, Madhusudan's entire oeuvre—produced in 19th-century colonial Bengal—encompasses and yet creatively ranges beyond the three stages of anticolonial struggle that the Caribbean revolutionary Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) spells out in his major work called The Wretched of the Earth (1961): assimilation, self-discovery, and rebellion. And Madhusudan's own rebellion—including his uncritical assimilationist approaches, his mimetic modes, and even his colonial mindset that one encounters in his early life—can all be seen in aesthetic, architectonic, in even metrical, and, of course, political terms. Now, before I dwell on the character and content of Madhusudan's literary and political rebellion, let me trace a few significant trajectories of his life and work.

Michael Madhusudan Dutta was born on January 25, 1824 (1230 by the Bengali calendar), in the village of Sagarda(n)ri—located by the Kapotaksha River—in the district of Jashore in present-day Bangladesh. He deeply loved his village and the river of his childhood, both of which continued to figure in his oeuvre. They also appeared in the very epitaph Madhusudan wrote for himself, thereby underlining his identity while also attesting to his rootedness. His father Rajnarayan Datta was a lawyer by profession. And Madhusudan's mother Jahnabi Devi was well-versed in ancient epics and Hindu mythologies. He was their only living child. Madhusudan went to a primary school in Sagarda(n)ri. During his childhood, he enjoyed the stories of the two ancient Sanskrit epics—the Ramayana and the Mahabharata—that his mother used to tell him. She also entertained her son with the stories from Mukunduram's Chandimangal (1590) and Bharatchandra Roy's Annada Mangal (1732)—the great verse narratives that were produced in precolonial Bengal.

Those stories his mother had told him remained with Madhusudan in profound ways—ones that would later come to inform and inflect his literary productions at more levels than one. In 1832, Madhusudan's entire family moved from their village to Kolkata (then known as Calcutta), where he attended the famous Hindu College (now Presidency College)—the best college at the time—an institution where Madhusudan studied Latin, Greek and English languages and literatures. And, indeed, that college played a crucial role in Westernising Madhusudan. True, he was then heavily under the spell of not only the Western literary canon and classics as such, but also the Western way of living. Madhusudan rejected Hinduism and converted to Christianity. This angered his father, who eventually disowned Madhusudan.

It was also during that period that Madhusudan fully devoted himself to writing poetry in English. In 1849, he published his first book called The Captive Ladie—consisting of a tale in two cantos and a verse narrative —a poetic production that surely evinced Madhusudan's command of English and even his artistry and poetic sensibility. But that work did not prove to be a success by any means. The Anglo-Indian educationist JED Bethune went to the extent of suggesting that Madhusudan should "employ his time to better advantage than writing English poetry" and that he should do well to write in his mother tongue.

Probably the most well-known stories of Madhusudan's life are that of his gargantuan ambition to become a great poet in the English language and that of his eventual glorious return to his mother tongue, although this return does not simply come to mean an orthodox, indigenist rejection or negation of English and European literatures as such—literatures on which he, however, continued to draw in most creative ways, attesting to an unprecedented literary internationalism in colonial India.

Madhusudan did not live a long life. He died when he was only 49. And the actual period of his literary productions in Bangla spanned about seven years—indeed a brief period during which he, however, produced five substantial volumes of poems in almost headlong succession: Tilottomasambhab Kabya (1860), Meghnadbadh Kabya (1861), Brojangana Kabya (1861), Beerangana Kabya (1862), and Chaturdashpadee Kabitabolee (1866). According to one authoritative account, between 1858 and 1862, Madhusudan published five plays, three narrative poems, and a volume of lyrics encompassing the variations on the Radha-Krishna theme. During the same period, Madhusudan also translated three plays from Bangla to English; among them was Dinbandhu Mitra's famous play called Nil Darpan.

Let me now return to Meghnadbadh Kabya—Madhudsudan's epic poem in nine cantos—which is a trailblazing intervention in the domain of Bangla poetry. Its staggering amplitude, its breathtaking intertextuality, its sonorous music coupled with the everydayness of the prosaic language that it poetically mediates, its polysemous vectors and valences, its relentless metaphorical imagination and its novel metrical adventures, and, above all, its reversal of hegemonically structured epistemologies and ontologies—including the Hinduism-sanctioned hierarchies—call for an extended discussion. But, owing to space constraints, I can only touch on a few aspects of Madhusudan's epic here.

To begin with, Meghnadbadh Kabya is a politically and aesthetically significant rewriting of the ancient Sanskrit epic Ramayana. This tradition of rebellious rewriting is also seen in so-called "postcolonial" literature—say, from the Caribbean poet Aimé Césaire to the Dominican-British novelist Jean Rhys to another Caribbean poet Derek Walcott, to mention but a few. Now, in Madhusudan's epic, to put it bluntly, Ram—who is otherwise considered the supreme being in many Hindu traditions—is not the real protagonist, but the Rakshasa monarch Ravan is. In fact, Madhusudan's epic decidedly zeroes in on the slaying of Meghnad, Ravana's eldest son. In Madhusudan's hands, Ravana—customarily and religiously demonised in dominant Hindu narratives—morphs into a real and even powerful human being, one who is capable of grieving, while Ram is depicted not as a god, but as an average human being with his frailties and even aberrations.

Now influenced and inspired by Shakespeare's versions of both humanism and anti-humanism—exemplified in that famous Hamlet passage starting with "What a piece of work is a man!"—Madhusudan surely and epically stages his own humanist and even insurrectionary sensibility that enables us to question, distrust, disobey, resist, rethink, even re-create. Indeed, in more senses than one, Madhusudan's epic is nonconformist, and, by extension, antifeudal and anticolonial—the first epic that fiercely mobilises the liberationist and emancipatory impulses in the era of high colonialism, while unsettling the existing order of things and thoughts. And Madhusudan's deep, active intertextuality that cross-fertilises Homer-Virgil-Dante-Shakespeare-Milton with the ancient Sanskrit epics is not politically neutral either; it means that making connections across geographic, linguistic, literary, and textual boundaries amounts to combating the colonially sanctioned and spatially imprisoned modes of becoming and being in the world.

True, Madhusudan and his works were always supported by Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820-1891), and, later, even by Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay (1838-1894), one who even ardently advocated the need for inscribing Madhusudan's name on the so-called "national flag" of India. But, as my own reading of Meghnadbadh Kabya reveals, Madhusudan never endorsed the kind of communally motivated, Hindu-centric Bengali nationalism Bankim promotes. But Bankim deeply admired Madhusudan not because of his rebellion, but because of his genius. Later, even Rabindranath Tagore, Pramatha Chaudhuri, and Buddhadeva Bose—all of whose anti-epical positions and characteristic lyrical proclivities are well-known—denigrated Meghnadhbadh Kabya; although, later, it was only Rabindranath who revised his position vis-a-vis Madhusudan's epic while moving in the direction of commending Meghnadbadh's thematic and stylistic innovativeness and elan.

Madhusudan's social farces—Buro Shaliker Ghare Ron (1860) and Ekei Ki Bole Sabhyata (1860)—are also unprecedented, groundbreaking interventions in the history of Bangla literature—works that significantly foreground the questions of justice and rebellion as well as the woman question with full force, although Madhusudan was not a feminist stricto sensu. But Madhusudan later wrote some brilliant plays, decisively focused as they are on the woman question, such as Sermista (1859) and Krishnakumari (1860)—plays that also mobilise emancipatory impulses, even if Madhusudan couldn't transcend his own male and class limitations in the final instance.

In this short piece, I could only scratch the surface of Madhusudan's work. But reinventing his work at the contemporary conjuncture amounts to reconceptualising the political value of an aesthetic that can enable us to stage our resistances to all forms and forces of colonisation and dehumanisation—direct and indirect—to say the least.

Dr Azfar Hussain is interim director of the graduate programme in social innovation and associate professor of integrative, religious, and cultural studies at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, US. He is also the vice-president of the US-based Global Center for Advanced Studies (GCAS).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments