The colonial, capitalist curation of ‘Bangla’ culture

When you, the reader, begin reading this piece, I need you to know that I am quite terrified and anxious about your response. I understand from the polarized debates that I have read on my social media—brimming with emerging artists and audiences in their 20s and 30s who have grown up consuming the glamor of Coke Studio and the fizzy drink itself in the sub-continent—that it is easy to sound like a spiteful critic. Yet, I am understanding of the rush of joy that my peers might feel to know that the franchise has finally arrived in Bangladesh. It has been, after all, the month of the commemoration of the lives lost in 1952 for Bangla, the mother-language of millions in this country. The collective and national memories of the struggle for Bangla is dense in the air this month, inviting people to recognise the need to preserve and protect their languages, be it either by publishing the first Mro-language grammar book in Bangladesh or by making nostalgic throw-backs to the precedence that Bangali nationalism takes over all else here for the formation of the nation state.

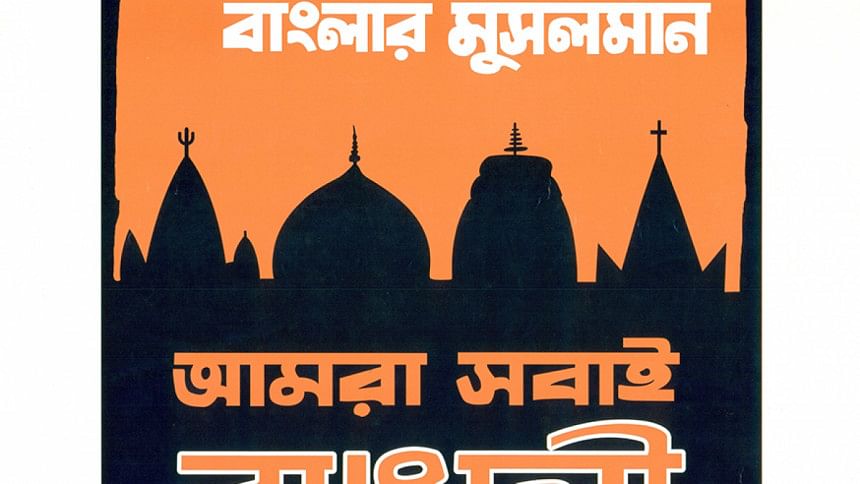

Please read the previous sentence again, and understand how these two different scenarios don't sit well with each other. This is relevant when discussing Coke Studio Bangla because Syed Gousul Alam Shaon—the creative producer of the project and managing director of the production agency, Grey Advertising Ltd.—defended the decision to use "Bangla" instead of "Bangladesh" in the title of the project so as to "go back to the roots". And I wonder whose roots he is referring to. His reference is this 1971 poster that wanted the citizens of the newly formed Bangladesh to forego all senses of any religious identities to forge an ethno-linguistic national identity instead. This is a national identity where being a Bangali, or a Bangla speaking citizen, would hold this new nation-state together rather than the legacy of Muslim nationhood that created East and West Pakistan. In fact, Shaon's reference to this sense of Bangali nationalism is so strong that Grey Advertising used the same font for the design of the title of the project. But maybe he has little cognizance of the repercussions that such colonial projects of modern nation-state making had on the people who were neither Muslim or Bangali and could not fit into either of these categories in 1947 or 1971. M. N. Larma summed it up well when he reiterated in 1972 that he was not Bangali, but a Chakma and a Bangladeshi citizen.

So, here we have a project that relies on that same erasure of identities, languages, culture and music to reconfigure "roots". And if it spoke only for Bangali people and culture, that would perhaps make sense although one can argue about the diversity of Bangali culture also. It would especially make sense because one cannot deny that the curator and producer of Coke Studio Bangla, Shayan Chowdhury Arnob—who spent a significant period of his formative years in West Bengal, studied in Visva-Bharati University and is well-known for his renditions of Rabindrasangeet—does embody the legacy of a united Bengal and hegemonic bhadrolok Bangali culture, whatever they might mean. However, the first episode of Coke Studio Bangla tried to make waves with a fusion rendition of the Hajong song, "Nasek Nasek" with a Bangla excerpt of Abdul Latif's folk song, "Dol Dol Doloni." And while one can easily say that Hajong—the language of a minority ethnic group of the same name inhabiting parts of north-east India and different parts of Bangladesh—is not Bangla, I also wonder out loud the cultural politics of embedding Bangla verses within a mainstream production of a Hajong song that will perhaps be the first introduction to any Hajong music at all for many in Bangladesh. Let us ask: why is it that a Hajong song cannot stand on its own on a mainstream entertainment platform in Bangladesh? Can it truly not, or was it simply not done that way?

When curated, hosted, composed, arranged, produced and instrumentalised by people who are not of Hajong, what happens to a Hajong song where only the vocalist is the only one bearing the history, language and representation of the song? But when especially keeping in mind how ethnic minorities have to assimilate into the languages and cultural identities of the powerful, model majorities, does Animes Roy—the brilliant Hajong singer—not become minoritized and tokenized on stage in the production of a song he should claim his own and his people's? One must remember that this is not an organic exchange and syncretism of cultures that have taken place over years of co-living or mutual embodiment; this is a staged and curated production of and by a project that claims to embody "bangali" identity alone.

Similar questions come to my mind when such a reconfiguration of the "roots" translate into "Ekla Cholo", the promotional production of Coke Studio Bangla that was first released as a fusion narrative of Gagan Harkara's Baul song "Ami Kothay Pabo Tare," Tagore's "Ekla Cholo Re," and Shironamhin's "Hashimukh." The video introduces us to many of the musicians and artists who feature in this season and yet, when the piece begins with Harkara's song, the Baul is a nameless, faceless figure in the shadows. A mere iconography of a cultural element of a region as vast as Bengal; a cultural product but not an artist in their own right, reduced to a trope and unrecognized for their artistry. Such a representation is reminiscent of the way Tagore himself made his own renditions of Baul songs and modernized them into studio-produced popular music, ultimately appropriating them into his strand of Bangali humanism with his own upper caste, feudal powers. So much so that now we commonly sing these musical pieces as Rabindrasangeet, but lost are the names and lives of the bauls and fakirs for whom these songs have historically been not just cultural commodities or products but embodiments of collective histories as well as religious and spiritual practice. Such tokenization reduces the vastness of what has now become a mere commodity in the name of "folk" for projects like Coke Studio Bangla, because the intricacies with which they are related to life, religion, politics and society would shatter the secular imaginary of the "Bangali". Secular representations of the Baul remove our gaze from events such as the imprisonment of the Sufi Baul Shariat Boyati in 2019, who was charged under the Digital Security Act 2018 for offending religious sentiments when he claimed that the Qur'an does not forbid music.

But Coke Studio Bangla and its reach for the "roots" had the government's support; in fact, Zunaid Ahmed Palak, the State Minister for the ICT Division was present as a special guest of the official launch event. Where the state not only makes permissible but also enables citizens with clout, power and ties to the ruling regime to define correct versions of religion and religious culture, I wonder what kind of cultural secularism it espouses with Coke Studio Bangla. But it wouldn't be fair to pin such repackaging of musical culture on the state alone; after all, it's not as if the state has taken much of a responsibility to do much for the preservation and sustenance of the traditions and livelihoods of Bauls over the years. In fact, the state's stakes in Baul traditions can be identified as borderline negligent, given how there has been little to no support for the communities before and especially during the pandemic. However, government support for musicians in Bangladesh in itself is generally low. How are musicians protected? What kind of industry support and infrastructure is available for them? What kind of financial security do musicians have in Bangladesh?

It is not at all strange for Coca Cola, one of the largest and most well-known multi-national beverage companies of the world, to come in here and fill a void for the support that music creatives need in this country. In fact, Coca Cola is only one among several companies, such as Unilever and British American Tobacco, who play this role often. It is, of course, relevant that even though the famed drink has been in this country for several years via franchisee arrangements, Coca Cola only established its own plant and arrived in Bangladesh as a company officially in 2017, and proceeded to invest millions in the following years to expand its market. You can get a sense of how recent this emergence is if you remember how rapidly and ubiquitously the brand of bottled water called Kinley spread in the streets of Bangladesh over the last 5 years in its lightweight and cumbersome plastic bottles. In fact, the U.S. Embassy's congratulatory social media post on the launch of Coke Studio Bangla reminds us of the expansion of Coca Cola in the sub-continent and all of the global south, and how such projects add glamor to their market portfolios.

We will talk about the environmental damage that this beverage company causes to the world another time. For now, yes, it is fitting for urban musicians who have to fend for themselves often to be happy when they find funding support that allow them larger stages with global audiences. After all, what is an artist without their audience? However, what do such intermittent financial opportunities mean for the long-term sustenance of the music industry as a whole? Coke Studio Bangla features the best of the best—artists who have already established themselves as national gems with their recurring bands of friends and acquaintances, and some cherry-picked new artists such as Rubayet Rehman and Masha who made their own road to fame by managing themselves and making their own content on the internet. While some musicians, instrumentalists and even a team of filmmakers and engineers find themselves celebrating such an opportunity, what does this mean for the everyday artist? Will this trickle down to build sustainable infrastructural support for emerging artists to learn and build their careers? Several of the recording and sound engineers of the first episode are either self-taught or educated in institutions abroad and the piece was not even mixed and mastered in Bangladesh, because there is not even a school for audio engineering in this country yet that can train such personnel. So, when one makes a claim that Coke Studio Bangla is good for the industry, I wonder in what sense, to what end and for whom? Does a project such as this function as an adequate substitute for the kind of educational, financial, social and market interventions that artists need for support and patronage? Coke Studio Bangla relies on a semblance of an industry that fends for itself and operates on its own free-market mechanisms without any support or regulation, and it is visible on the first episode when you see that the only women on the stage are the back-up vocals and all the instrumentalists are male-bodied. In a society where masculinity dominates and women need infrastructural support for mobility and access in the urban public sphere, they remain relegated as soft-spoken singers and graceful dancers but not as bassists or drummers.

So, yes, I am worried that you, the reader, will be angry at this piece because I am not entirely confident about the good that the emergence of this project can do here even though I also empathize with the desires and needs for such opportunities. But this is not a review of the musical performances of Coke Studio Bangla and I do not negate the hard work and struggles that most of these artists must have gone through to create their art. Instead, this is a critique that takes into account the everyday politics of being a musical artist in this country and the nuances that must be taken into consider when the artistry differs by language, gender, faith and location.

Maliha Mohsin is a writer, researcher, DJ and community organiser based in Dhaka and Vienna.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments