Where can domestic violence survivors actually go?

On this year's International Women's Day, which is being celebrated across the country and with much grandiosity in Dhaka, I want us all to think of Yasmin Ara, a young woman from Satkhira, who has been thrown out of her home by her mother-in-law a few months after losing her husband.

Three years ago, at the age of 15, Yasmin was married off to Shafiul Islam, a mason by profession. She had studied only until Class 4, and was never engaged in any paid work before or after her marriage. Her husband was electrocuted to death while working at a site few months ago, leaving behind Yasmin and their two-year-old daughter, Dia. Shafiul's employer did not pay them any compensation for the occupational death.

Soon after Shafiul's death, Yasmin's mother-in-law, Aleya, asked her to visit her father's house for a few days. Afterwards, when Yasmin tried to return home, Aleya refused to let her in. Yasmin saw that the door to her room was locked. After much insistence, Yasmin managed to take a look inside her room only to find that all her belongings, as well as that of her daughter's, had been removed without a trace. Aleya then said to Yasmin, "Tomar ekhane ar kichhu nai, tumi tomar baaper bari chole jao (You have no reason to stay here now, so return to your father's house)."

Aleya also indicated that since Yasmin only bore a daughter, she had no right over the family home. Nevertheless, Aleya declared that they would come to take Dia once she turned 10. Thereafter, Yasmin moved back to her father's home with her daughter. Her father's family is much poorer compared to her more well-off in-laws, as her father works as a daily labourer, and her mother is a homemaker. They are barely able to feed themselves.

I came to know of Yasmin's case through a pilot project I oversee named "Ar Na," being implemented by Brac in Satkhira and Rangpur. As part of this project, over 800 frontline staff in 50 branches are being trained to use a web app to report incidents of violence against women and girls in their working areas. Yasmin's case was reported by Tania, a frontline staff member of Brac's microfinance programme, who came to know of Yasmin's ordeal when engaged in her daily loan collection in Yasmin's neighbourhood.

After a case is reported, a small team of case managers work to connect the survivors with required support services through referral. Yet, in order to refer survivors of gender-based violence (GBV) to a local service provider, a mapping of existing support services at the upazila level is of utmost importance. Shongjog, a web app, shows the availability of six main types of support services for GBV survivors at the upazila level, based on a nationwide service-mapping conducted in 61 districts covering 435 upazilas across Bangladesh. It categorises service providers into six main categories: police stations, legal aid, social protection (i.e. livelihood opportunities), psychosocial support (e.g. trauma counselling), safe/shelter homes, and medical aid/health services.

When the case manager visited Yasmin to gather facts about her case and ask her about the kind of referral support that she needed, Yasmin expressed her desire to take legal action to secure her daughter's property rights, and do whatever it took to secure her daughter's future. Yet, she exclaimed with regret, "Mamla je korbo, mamla korte jawaro taka nai (I do not even have the money to travel to court, let alone to file a case)." She also mentioned that she had no means to feed herself or her daughter, and that she was in urgent need of financial support or a livelihood opportunity. While Yasmin articulated her need for legal aid and social protection, the case manager also noted that she needed psychosocial counselling to overcome the traumatic experience she had faced.

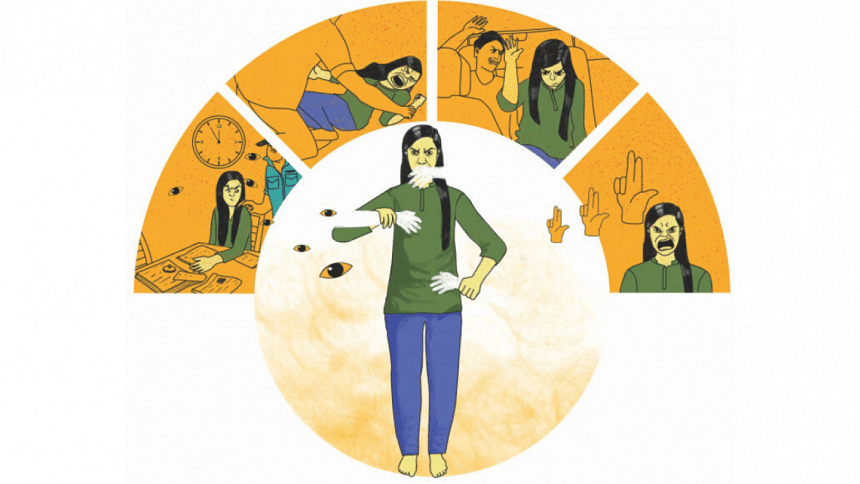

Yasmin's story encapsulates the experience of too many Bangladeshi women today. The vast majority of cases we have received reports of through the Ar Na project all relate to young women (aged 27 years on average), facing domestic violence from their husbands or in-laws, or both. The type of support that these survivors most commonly need are legal support, social protection (i.e. livelihood support), and psychosocial counselling. So how readily available are three of these support services at a national level, that a survivor in Yasmin's position urgently needs?

The National Legal Aid and Services Organisation (NLASO), was set up to provide legal aid to those otherwise unable to afford legal services, and has established district legal aid committees in all 64 districts of Bangladesh. Legal aid committees have also reportedly been constituted at the upazila and union levels, though information about these are not available on the NLASO website.

For those unwilling to take microcredit loans, or unable to meet the loan disbursal criteria, two of the social protection programmes being implemented by the government are of particular relevance, both of which we are in the process of claiming for Yasmin. The Department of Social Services has a cash transfer programme called Allowances for the Widow, Deserted and Destitute Women, which makes monthly payments to the tune of Tk 500. However, application for this assistance does not automatically guarantee transfer of cash for anyone who applies. It is subject to selection by a committee, and the official selection criteria state that priority will be given to "i) Senior most widow, deserted or destitute woman; ii) Widow, divorcee or deserted woman; and iii) Wealthless, homeless and landless."

The Department of Women Affairs (DWA) has a programme named Women's Skill Based Training For Livelihood, which provides training to women in order to develop skills on certain trades so they can earn a livelihood. As part of this programme, the DWA in Satkhira, for instance, provides training on Microsoft Office Word application, mobile phone servicing, handicraft, tailoring, and beauty services. The training is provided free of cost and participants receive Tk 100 for each day of attendance. However, batches are taken only every quarter, and places are limited to 25 or so people.

The situation is the grimmest for psychosocial support services, with it being identified as the least available out of the six service types covered by the Shongjog service map. Other than the One-Stop Crisis Centres (OCCs) in 12 medical college hospitals and certain public hospitals, psychosocial counselling services remain few and far between. Most alarmingly, the largely foreign funded Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence against Women, which started setting up the OCCs in 2000, is currently in its last phase, which makes the future of even the OCCs uncertain. The nearest OCC to a survivor in Satkhira, like Yasmin, would be in the neighbouring city of Khulna.

Yasmin's story teaches us two important lessons. Firstly, even where services are available, and are provided free of cost, it does cost money to travel to the service provider, which are typically located in far-off locations. Even if the required support service is available for free, survivors often do not have the means to afford the transportation cost needed to reach these service providers. For this reason, survivors need immediate financial assistance so they can, at the very least, bear the immediate and incidental costs associated with experiencing gender-based violence and seeking support services as a result of it. Secondly, the two social protection programmes outlined above (and the more than a hundred listed) do not necessarily guarantee selection even if applicants are proven to be GBV survivors, and are not designed to cater to their needs.

Therefore, as we transition into a middle-income country, and foreign funding for NGO projects on violence against women shrink, a social protection programme designed to address the unique needs of GBV survivors is the need of the hour. This programme should, at the very least, provide survivors with immediate cash transfers in the short term to meet pressings costs, while ensuring their economic empowerment in the long term.

Names of individuals have been anonymised to protect their confidentiality.

Taqbir Huda is the advocacy lead for the Gender Justice and Diversity Programme at Brac.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments