Brac’s lesser-known gift to Bangladesh: Vaccination push

If one were to explain what work the organisation he built has done or how it has contributed to Bangladesh's development, the task would be next to impossible; the list is endless. Instead, if we were to ask what hasn't this organisation done, the answer would be brief though it would take quite a lot of research to find it.

We are talking about Brac and Sir Fazle Hasan Abed. Nobel laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus may shed some light on the above-mentioned questions:

"It is certainly not an exaggeration to say that there is hardly anyone among the 170 million people of Bangladesh who do not benefit in some way from Abed's programmes or enjoy products and services provided by his organisations."

This testimony from Dr Yunus about Brac and Fazle Hasan Abed is probably the most impactful statement about the man and his organisation.

The 50 years since Bangladesh's birth coincides with Brac's first 50 years. Brac and Fazle Hasan Abed are synonymous. There is no scope of discussing one without the other.

Brac has been discussed more profusely after Fazle Hasan Abed's death. This was probably because he was more interested in getting the work done than promoting himself or his organisation. He was self-effacing, kind, soft spoken, and humble; yet he possessed a steely determination and willpower to make his vision a reality. This is evident in every aspect of his life and work. A successful organisation's fate, its ability to survive are invariably speculated about after the death of its founder. In this regard, Brac is a shining exception.

Before embarking on the eternal journey, he left behind the world's largest private sector development organisation—Brac, which has an unmatched institutional structure. Even in absentia, he is fuelling Brac's onward journey through his guiding principles. It is as if there's no end to the half a century old organisation's work extravaganza. Apart from its home country, Brac has reached all over the globe including conflict-ridden countries like Haiti and Afghanistan. From providing informal education to establishing a university, from offering micro-credit to operating a full-fledged bank, everywhere he left his extraordinary mark.

His brilliant mind was kept busy in coming up with unique solutions to every kind of problem. When the threat of an epidemic affecting poultry and livestock was imminent, Brac reached out to one village after another with vaccines carrying them inside ripe bananas to keep them cool in the absence of air conditioned containers. Reviving the fading art of producing Jamdani and Nakshikantha, establishing Bangladesh's very own lifestyle brand Aarong, its contribution to promoting oral saline, curing tuberculosis, Brac's footprint has reached every developmental path.

For him, development meant human resource development. He believed that merely donating money or giving a loan to a poor person was not enough. With the money Abed believed it was important to give the person some direction and training so that he or she would know how best to utilise the money in the best possible way. Brac has always given equal, and sometimes more importance to the personal development of human beings along with rehabilitating them or providing micro-credit to them.

And women and the poor have always been at the core of all of Brac's endeavours.

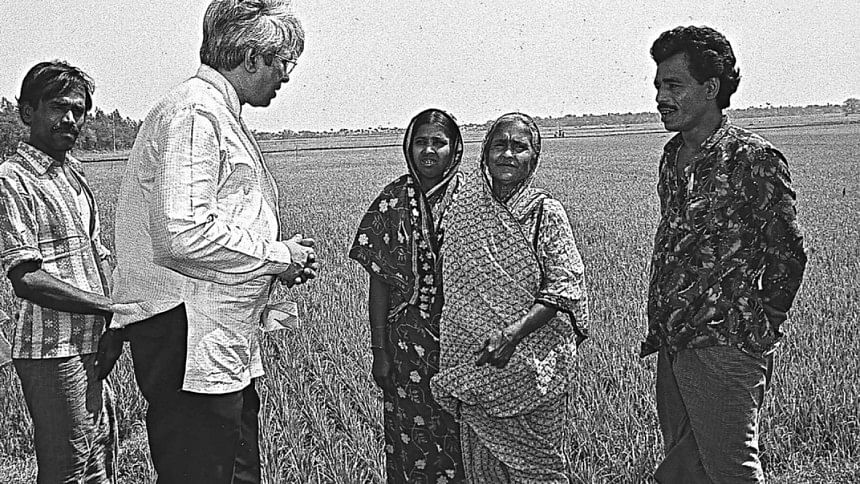

A single article can barely give a glimpse of the immense work of this man and his organisation. Thanks to a book writing opportunity, I have had the good fortune of enjoying Fazle Hasan Abed's company for an extended period. I was blessed to be able to travel with him to many parts of the country, to talk to this legend, and have extensive discussions with him. I had a firsthand account of the work that Brac does, and the opportunity of knowing the organisation from its core. Based on that experience, I will try to shed some light on a comparatively less discussed topic; Brac's vaccination programme.

One day, while heading towards north Bengal, we were sitting in a car. I asked Abed, when and how was Brac born?

Giving his trademark smile, he mentioned, I didn't start the work after Brac was formed, rather, it was the other way around. On 17 January, 1972, I returned home from London. The country was in shambles at that time. People were without work and food. I couldn't bear such a sorry state of the nation for which we had to sacrifice so much. The Pakistanis were defeated, but they had destroyed everything before leaving. At that point of time, I came to know about the Shalla area of Sylhet, where the majority of inhabitants were Hindus. The Pakistan Army had caused mayhem in that area and left it totally devastated. When I went there I thought that many people would be working in the city areas, but few would be interested in extending their help to rehabilitate people in a remote village like this. I decided to save the people of Shalla. When I started the rehabilitation efforts, I felt the need to involve an organisation. I had started working for Bangladesh's independence in London through 'Action Bangladesh' and 'Help Bangladesh'. I formed 'Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee', abbreviated as Brac, in order to rehabilitate the people of an independent Bangladesh. This is how Brac was born in February, 1972.

Brac is a product of our Liberation War, and it is as old as Bangladesh.

Brac's activities are not only geared towards the economic rehabilitation of people or to make them self-sufficient, but also for the basic act of saving lives through innumerable efforts such as bringing down child mortality rates. Issues that repeatedly came up during the discussions with Abed were: saving poor people's lives, vaccination, bringing down child mortality and birth rate, etc.

The year 1979 was termed as the International Year of the Child. From that year Brac became the first organisation to highlight the need of vaccinating infants and expectant mothers. Abed mentioned, 'At that time, tetanus was responsible for the death of 7 percent newborn children. The lives of this 7 percent could be saved if the expecting mothers were given 'tetanus toxoid injection.'

Fazle Hasan Abed came from a family of landlords. He went to London with a romanticised vision of being the first naval architect of the nation. However, half way through that course, he changed direction and completed a four year professional course on cost and management accounting instead. Eventually, he ended up working in a series of high profile jobs with handsome pay in different multinational organisations in the UK, USA, and Canada. As a stark contrast to his earlier persona, Abed built an organisation that had the interests of young mothers, infants, the needy and the poor, as well as issues like vaccination or decreasing the birth rate at its core. It was his mother who had always inspired him to think this way about the poor and the needy. His mother left a deep impression on him, which Abed has mentioned on many occasions.

At the beginning of any work, Fazle Hasan Abed would always take the initiative to collect the primary information. In 1979, the then president Ziaur Rahman asked him, "What can we do for the children?"

Abed replied, "The child mortality rate is too high in our country. When a country has a high infant mortality rate, it also shows signs of high birth rate. We have seen that once the infant mortality rate comes down, within a few years, the overall birth rate also starts declining. High infant mortality rate and population explosion are impediments towards our progress and advancement."

In that discussion, the issue of providing tetanus injection to the mothers came up, which the president approved of. Abed came to know about the issue of tetanus injection from his friend Dr Lincoln Chen, who was working at the icddr,b. Not only this, he also came to know about some other vaccines, which might prevent the death of many infants. Collecting the vaccines, training the service providers—none of that would be all that difficult. However, a major challenge came in the form of vaccine preservation. These vaccines had a mandatory storage temperature rating, which demanded some specific refrigerators, which were not available in every thana. It might even take five more years to ensure uninterrupted electric supply in all those thanas to keep the refrigerators running. Naturally, the vaccination programme went into a hiatus. But Brac did not stop, nor did Fazle Hasan Abed. He realigned his efforts towards combating diarrhoea. He started reaching out to the doorsteps of 68,000 villages of Bangladesh with an oral saline made of salt and molasses. Not only in Bangladesh, he also reached Indonesia and Africa with this oral saline. His success spanned across the globe.

Finally, after 6-7 years since the initiative was first taken, the vaccination programme could be jump-started.

In 1986, the opportunity knocked at the door and a chance to materialise the vaccination initiative became a reality. Brac would do the entire work, but they would also utilise the public sector infrastructure and human resources. Fazle Hasan Abed always believed in work sustainability. If Brac completes the work, but the public sector representatives are not involved, then how will the initiative continue to function in the long term? In such a situation, if, for some reason, Brac had to exert its focus in some other endeavour, the vaccination programme would have stumbled and lost its momentum. At that time, there were only four divisions. The arrangement went like this; Brac would focus on Rajshahi and some parts of Chittagong, while the government would take care of Dhaka and the remaining areas of Chittagong. CARE would work in Khulna division. The initiative to vaccinate against BCG, DPT, Polio and Measles started. Although the government and CARE was a part of the initiative, it was fully planned by Brac, and they also arranged the training.

In the year 1990, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a survey on the vaccination status of children. In this survey, it was discovered that the areas covered by Brac had completed 80 percent vaccination efforts. CARE achieved 65 percent success in Khulna division, while the government bagged 55 and 50 percent vaccinations in Dhaka and Chittagong division respectively. WHO recognised Brac's success.

Without doubt, it was only due to Fazle Hasan Abed's efforts that motivated the government to actively participate in this vaccination programme. The top leaders were due to attend and participate in the United Nation's Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990. Only the countries that would manage to fulfil the requirements of 'Universal Child Immunization' were supposed to get an invite. The then Unicef chief James P Grant delivered this message to president HM Ershad. Eventually, as the head of the state, Ershad and as a representative from Brac, Fazle Hasan Abed were invited to join this prestigious summit of the United Nations, where Bangladesh's role was deeply praised.

In 1980, the newborn mortality rate was 135 out of a thousand and the child mortality rate was 250 out of a thousand. After a decade, in 1990, the same rates became 90 and 120, respectively. The death rates fell by half just within 4 years of starting the vaccination drive. Surveys conducted during those times reveal that the birth rate also went down.

Today, Bangladesh is well ahead of many other countries, in terms of children and mother's vaccination. The vaccination issue again came into focus during the Covid situation. The organisation that achieved this exemplary success is none other than Brac. Just like many other fields, this achievement, too, solely belongs to the legendary Sir Fazle Hasan Abed. He was the quintessential champion of Brac, a brother to all Bangladeshis, our very own Abed Bhai.

Golam Mortoza is author of the book 'Fazle Hasan Abed O Brac'

(Translated by Mohammed Ishtiaque Khan)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments