Why should we need to demand safe roads?

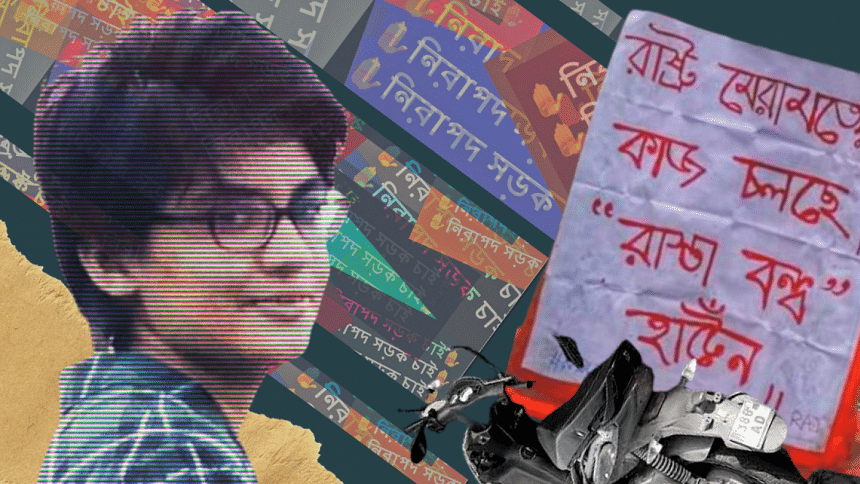

Maisha Momotaz Meem, a 22-year-old student of English at North South University (NSU), was riding her scooter on Kuril flyover to her university on April 1 morning when she was run over by a covered van. It was being driven by someone who only held a licence for driving light vehicles, not heavy ones such as a covered van.

The driver of the Meghla Paribahan bus which hit and killed two pedestrians in Gulistan on January 8 this year had been driving it with a light vehicles licence for around two years.

When a pickup van ran over and killed five brothers on the Chattogram-Cox's Bazar Highway on February 8, it had already been operating for three years without updated fitness clearance papers, route permit and tax token.

According to police data, 5,088 people were killed in 5,472 road accidents in 2021. Latest data from the Bangladesh Road Transport Authority (BRTA) indicates that at least one million registered vehicles are being driven by unlicensed drivers.

It would be naive to expect a driver, who has been operating a heavy vehicle without a proper licence for years without being caught, to be responsible behind the wheel.

So, how many thousand more avoidable murders on the roads will it take for the authorities in charge of making our roads safer to take notice?

Unfortunately, this lax attitude of authorities is not unique to how they handle issues of expired or missing vehicular documents.

Back in 2018, after students from schools, colleges and universities protested for road safety, the Road Transport Act, 2018 was introduced and came into effect in November 2019. But it is yet to be fully implemented.

Neither statistics—the number of deaths and road crashes rose by 29.86 percent and 30.34 percent, respectively, in 2021 from 2020—nor the daily news of deaths caused by vehicles seem to push the authorities towards the urgency that this epidemic demands. Why else is it that the draft of the National Road Safety Strategic Action Plan 2021-2024, which was prepared over a year ago, is yet to be approved? The fact that road crashes and resultant deaths have now become a national problem seems obvious to experts and ordinary citizens, but not to those who could actually formulate laws and plans to help curb these deadly numbers.

A high-powered taskforce, formed in October 2019 to tackle road crashes and bring discipline to the sector, led by the home minister, began its journey with a 111-point recommendation. Though it took several decisions during its three meetings till June 2021, only one has been fully implemented: appointing a focal person from four ministries concerned to oversee the implementation of all other decisions.

What hope is there for a country—soon to become a developing country—to be a safe one for its citizens if people are being killed on the roads daily, with little intervention from the authorities besides what's on paper?

Many are looking at Meem's death through a misogynistic lens: "Why does a girl need to ride a scooter anyway?" I believe the question can be tweaked to ask: "Why aren't our roads safe enough for women to ride scooters on?" Why must they practise independence while treading a line between facing harassment or meeting death? And if it's so unacceptable for women to drive their own vehicles, what is the alternative? To keep boarding buses wherein they face harassment from other passengers simply for being women? Or to search the horizons and wait for one of the mere six-women-only BRTC buses that currently operate within the capital?

Others are wondering why students, especially from NSU, have not taken to the streets in larger numbers to protest their peer's death. Again, why must students, who are supposed to be able to uninterruptedly pursue their education, be forced to come out and demand as basic a need as safe roads from the government? This concept baffles me now as much as it did in 2018. Even if students do take to the streets now, what would change anyway? We all remember too well how the state responded to their legitimate demands in 2018. And even the protests in November last year don't seem to have moved the authorities to action.

Having laws and regulations on paper, holding meetings with specialised task forces, conducting traffic safety weeks are all well and good. But it's past the time now for the relevant government bodies to step up, smell the road accident deaths, and actually implement their myriad decisions. Every day that they don't, we lose tens of Bangladeshis to avoidable deaths—for which only systemic flaws can be blamed.

Afia Jahin is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments