Coke Studio Bangla's 'Prarthona': Caught between subversion and co-option?

The second song of Coke Studio Bangla, titled "Prarthona" (Prayer), was released on the eve of Ramadan this year. It was the same time when both the mainstream and social media flooded with updates, news, and views on the harassment of a Hindu female college teacher by a Muslim male police constable for wearing a teep on her forehead. Feminists and social justice activists started protesting the incident by updating their Facebook profiles with photos of themselves wearing teeps and demonstrating on the streets. It was also the same time when social media was taken over by sexist, masochistic comments about the killing of a 21-year-old student of North South University (NSU), who was riding her scooty, by a covered van in a road accident. Many blamed the victim for her "transgression," criticising her attire and her parents' decision to get her a scooty. My Facebook newsfeed was swamped by comments and discussions on all of these events.

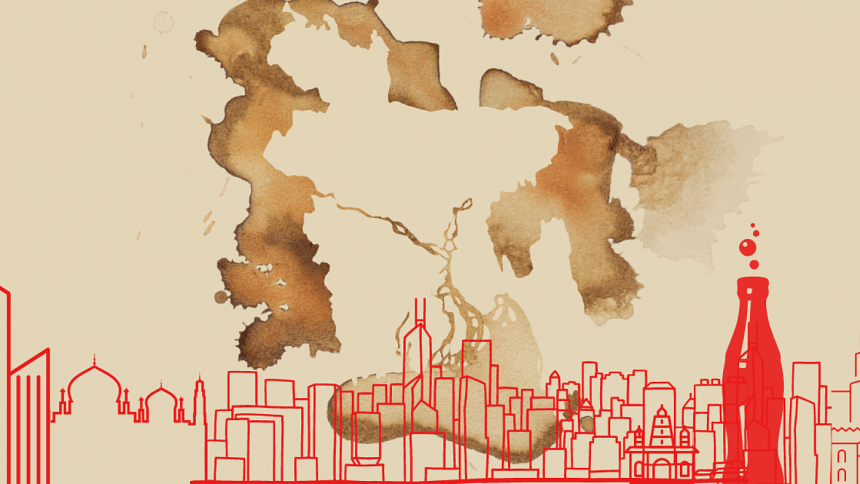

Perhaps these juxtapositions—where people either produce or criticise orthodox, fundamentalist narratives and practices that exploit women and other minoritised communities, while cherishing the release of a spiritual and subversive music composition that celebrates an egalitarian divinity—are reflective of the unique realities of a postcolonial, neoliberal Bangladesh that is shaped by myriad forces of globalisation.

On the one hand, globalisation has opened doors for foreign direct investment (FDI) and invited The Coca-Cola Company to tap into a growing beverage market worth Tk 2,500-3,000-crore in Bangladesh. Many Bangladeshis are taking pride in the fact that Coke Studio, which sponsored music production in Pakistan, India, Brazil, and other countries, has made a grand entrance into their country and opened doors for supporting local musicians and promoting local musical traditions. Forgotten here is Coca-Cola's long problematic history of lawsuits for racial discrimination against African-American employees and polluting air in the US, aggravating groundwater depletion in India, conducting cruel animal testing, monopolising markets in the US, Europe, and Mexico, and being the single largest plastic polluter in the world—to name just a few. Coca-Cola recently invested USD 74 million to establish a plant in Bhaluka, Mymensingh, and promised to expand not only the plant and infrastructure, but also its market and portfolio in Bangladesh. Coke Studio Bangla and its latest release of "Prarthona"—a celebration of, as Coke Studio Bangla describes, "the eternity of virtue and how the real magic of devotion can withstand the test of time, connecting generations, old and new"—are parts of Coca-Cola's massive portfolio building initiative in Bangladesh.

On the other hand, the same globalisation has been strengthening the ultra-orthodox Wahhabi-Faraizi-Deobandi-Salafi versions of Islam in this region that originally embraced Islam through more egalitarian and Persianised conquerors, traders, and Sufis. The free flow of Saudi petrodollars, as well as locally sponsored orthodox religious educational and other charity programmes, filled the vacuum in a country that failed to provide social safety to its working-class and most vulnerable communities. The influence of missionary-style religious charity, widespread circulation of orthodox narratives on social media, the government's need to appeal to conservative voters and its strategic softer stance towards certain fundamentalist groups to secure an endorsement, as well as the globalised political consciousness of the returned Bangladeshi (mostly male) labour migrants—who are aware of global and class inequities, but reject democratic politics in favour of authoritarian Islamic regimes as a way to achieve prosperity that they have witnessed in the Middle East—have been widely influencing everyday vocabularies, gendered norms and practices, and other expectations in Bangladesh.

Against this backdrop, Coke Studio Bangla's choice of two songs—"Allah Megh De" and "Baba Maulana"—and their release on the eve of Ramadan offer an intriguing scope to critically reflect on both the imperialist-capitalist invasion of the global Coke empire, as well as Coke Studio Bangla's powerful subversion of the dominant, orthodox Wahhabi-Salafi popular rhetoric in Bangladesh. Both the devotional songs were written and composed by authors/composers/singers who did not grow up in Muslim families. "Allah Megh De" was written and composed by Girin Chakraborty, who was trained by legendary musicians Allauddin Khan and Aftabuddin Khan. Great folk singer Abbasuddin Ahmed later sang the song and popularised it. "Baba Maulana" was written and composed by Ramesh Chandra Shil, who was popularly known as kobiyal Ramesh Shil or Ramesh Maizbhandari. Ramesh Shil grew up in a Hindu family in Chattogram. His songs addressed anti-colonial and social justice struggles, including the revolutionary raiding of the Chattogram armoury, the self-sacrifice of Surya Sen, the non-cooperation and the Khilafat movements, the 1947 Partition, famine, and the Language Movement. He transformed kobi gaan from a medium of entertainment into a tool for political and social justice activism. He had a long history of organising with the Communist Party and was a strong supporter of Jukta Front in the provincial election of East Pakistan in 1954. He got arrested after the Jukta Front government was dismissed by the Pakistan central government. He was also a follower of the Maizbhandari Sufi tradition.

Because of the origins of the authors and composers of the "Prarthona" songs, we see an intriguing amalgamation of language that incorporates a prayer to "Allah"—the monotheistic God—by saying that the drought is happening because the King of Clouds got angry and so only Allah can now bestow clouds and rescue the suffering community ("Meghraja gomraiya roise megh dibo tor keda"). Similarly, "Baba Maulana" describes "Maulana" as a "doll of light" ("Noor-er putula baba maulana")—a metaphor that would perhaps be heavily discarded in anti-pagan Abrahamic religious traditions.

The fact that the lyrics, as well as the choice of the two songs, are creatively subversive does not lessen the fact that Coke Studio Bangla is still situated within the political economy of what some scholars have described as "coca-colonisation" to refer to the aggressive production and marketing strategies of Coca-Cola exploiting resources and environment, and privileging global as well as local elites. Through the "Prarthona" composition, Coke Studio Bangla challenges the Wahhabi/Salafi dominant narratives of Islam and promotes an indigenous, mystical, egalitarian, and subversive new "Muslim" identity. However, it does so by appropriating indigenous, folk, and Sufi music traditions, which historically took place in dargahs, and placing it in an experimental studio. Within the mediated space of the studio, Mizan Rahman, who was never involved with the Maizbhandari tradition, becomes the chief vocal for "Baba Maulana," and Momtaz Begum's usual flamboyant self and her non-elite rawness is turned into a sanitised and derivative "mellow, controlled vocalisation." In this way, Coke Studio resuscitates minoritised musical traditions, but then appropriates as well as commodifies them to produce an indigenised version of "modernity."

Nafisa Tanjeem is an assistant professor of gender, race, and sexuality studies and global studies at Lesley University in the US. Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments